|

Bullets Fly in a Forgotten Land

Ogadenia Separatists fight Ethiopia

By Jonathan Alpeyrie

At the hotel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a car waited for me at the

entrance, and I quickly got in discreetly so people didn’t see the

activity. It was a small mini van with two students and a driver, who

work for the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) in the capital.

Lately, I’ve been concentrating on East Africa producing some photo

essays of the main rebel groups fighting in Ethiopia. This is my second

trip to the country and I was delving into new territory. A long

nine-hour bus ride ensued. The driver chewing on leaves, which gives

him energy, drove like a maniac. Passing camel herds and trucks way too

fast, we meandered through many checkpoints that became more frequent

as we moved eastward towards Ogadenia.

Finally

in Jijiga, a medium size town with a population of 20 thousand, I

immediately sensed the dirt, the poverty and loads of government troops

littering the landscape. I was the only white man around. The van

pulled into a small, side street where there was a safe house. My

guides got me out very fast and took me inside to a small courtyard

where children were playing. There I entered the house where 4 ONLF

student members were waiting. I ate dinner with them, and they told me

to wait until night fell to leave the city without being noticed. It’s

too easy to spot a white person in these parts.

In

the cloak of darkness, three members loaded their backs with my gear

and escorted me. Once outside, we were careful to use small, rarely

used and nearly empty streets. Some people noticed us and gave us

strange looks, because I was with them. We soon left the outskirts of

the city to venture into the wild. We walked very fast to escape the

soldiers patrolling around. The first few hours were easy to walk

through plain dirt scattered with a few bushes. When we hit the hills,

the terrain transformed: rocks, bushes armed with thorns ripped through

my skin and clothes. I tired trying to keep up with the students. After

walking for 20 KM, they stopped in order for me to sleep a little. I

waited for a small rebel force to pick me up and take it from there.

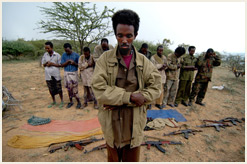

Early

in the morning a few hours later, I awoke pressing forward up the hill.

We reached a small mountain where I saw a few heads coming out of the

bushes. There and then, I knew I had made my first contact with the

ONLF. As soon as I arrived on top, a few dozen very nice but curious

rebels and their commander Sawini greeted me. Soon after I was

introduced to Dohozo who would become my translator and above all my

friend throughout the trip. They placed my gear near a trip, which

would become my home for one week. But I did not know that yet.

I

started shooting with my camera, their everyday life in the bush:

praying, cooking, patrolling around the neighboring hills. It was also

the month of Ramadan so they were resting. One night I heard gunshots

coming from a nearby government positions they told me we were

surrounded. For my own security, we had to break our camp when the

right time came. A few days later, after a storms and rain of bullets

hitting our small force, I heard fighting at night. The next morning

they told me they counterattacked with a few men and forced the

government soldiers to retreat. We were free to move south from this

trap.

We

walked for 8 hours straight each day, going up and down the hills. We

took a dirt road used by government forces to bring in reinforcements.

At any time an ambush could occur, so everyone was on guard. They

always placed me in the middle of the column. Each night we made camp

while soldiers secured the area, they gave me a plastic cover so I

could build a tent to protect myself and gear from the elements. As we

moved south, we met more and more civilians, who usually sheered at the

presence of the ONLF fighter. This had a doubling effect with a white

person accompanying them. The rebels also told me to be careful, as

spies can always mingle with the locals.

After

days of walking more gunfire was heard, a ONLF unit, which had been

attempting to overrun a government position, was held up in a village a

few KM away. A few ONLF came back with one wounded man, whom they

treated in front of me with a bullet wound. He had been hit on the

shoulder while attacking the position, while some of his fellow

soldiers were killed straight out right. The others were left behind

after a hole was dug and left there. Many civilians came to supply us

with food and water as well as information on enemy movement. We waited

there for 5 days while the defense minister and his cabinet walked 400

KM to meet us with more men. It is so rare for a Western journalist to

come to these parts, that they made the dangerous trip to meet me. He

finally came during a storm. We talked about the ONLF, their plans and

my plan. Afterwards, they all reunited to talk about the next move.

We

went West, with the lead element of the 160 strong group running into

an enemy infantry column, and a brief firefight followed. When bullets

fly, I hit the ground. If badly wounded, I would have little chances to

survive because no city can be reached in less than a five days walk.

We

finally came to a large village of 800 strong, all of the villagers

gathered by the ONLF so the minister could deliver his speech on the

progress of the rebellion and its consequences. War dances are

organized inside the village by some ONLF soldiers to stimulate the

people. The civilians often join in and some soldiers fire guns in the

air. The next day we left the village to move north East.

After

a few days walk, the minister, his cabinet and half of the men split to

move back towards the Somalis. I continued North with 30 ONLF troopers

to finally get back to where I came from four weeks earlier. We walk

each day through mud and hills with intermittent storms. One day, while

moving through a gully, I heard a gunshot and fell on the ground

quickly. I hit my head on a rock and was shot. We keep going to reach a

nearby hill, which I could see from a distance. The next morning only

10 soldiers were selected to get me closer to Jijiga. We walked from

night until day through the hills until the civilians found us. At this

point, I’m beyond tired. They helped to carry my gear. We continued our

move North after saying goodbye to Dahozo and the remaining nine ONLF

soldiers.

We

had to hide more than once as Somali soldiers protected the town. As

soon as they left, we rushed forward closer to the city lights

glimmering from a distance. When flashlights got closer, we’d hide.

Thus, we moved slowly, resting and walking, taking 15 hours to get to

the outskirts of the town. The sun would rise in a golden yellow light

would reflect on the mosques just as they started their morning

prayers. The rebels hid me in another safe house for a few hours until

a car picked me up to drive me back to Addis. I said my goodbyes to the

rebels and thought I could understand more about their struggle.

Opinion and History of the ONLF Rebellion

By Jonathan Alpeyrie

Ogadenia

is a forgotten land wrecked by war and very harsh living conditions.

The region, which is still today at the center of the volatile Horn of

Africa, has seen little economic progress since its first taste of

brief independence in the first Ogaden war of 1977/78. In 1991, the

Meles government came into power. The region remains to this day a

barren land with only two main roads a few large towns like Kabri

Dahar, Jijiga and Quabribayah, which are controlled by government

forces trying to tame the rebellion led by the ONLF (Ogaden National

Liberation Front). However, to fully understand the war of today’s

Ogadenia, one needs to go back further in history and take a look at

the European influence in the region.

With

the defeat of the Somali forces and Ogaden rebels in 1978 in the hands

of the Russian backed Ethiopian army, Ogadenia was reconquered

entirely. Many of the militia survivors retreated to fight another day.

Three years later, the ONLF was created to continue the fighting to

force the Ethiopian government into giving Ogadenia its long due

independence. The ONLF, which was Founded in 1984 by Abdirahman Mahdi,

the Chairman of the, Western Somali Liberation Movement Youth Union,

systematically recruited their own kin and replaced WSLF in the Ogaden

as the WSLF support from Somalia dwindled and finally dried up in the

late eighties. By 1993, the ONLF fully consolidated its support among

all of the Ogaden Somalis in Somalian territory under Ethiopian rule.

In 1994, the ONLF was a fully functional military force and Chairman

Admiral Mohammed Omar Osman was reelected for a second term in 2004.

The

ONLF announced elections in December 1992 for the five Ogaden

districts, and won 80% of the seats of the local parliament. When

Ethiopia tried to force ONLF to accept a new constitution and the ONLF

refused: the Meles government declared war on them. The rebel faction

continues to operate in the Ogaden as of 2006 and is the target of

full-scale military operations by the Ethiopian army after ONLF stated

that it would not allow Malaysian oil company Petronas to extract oil

from the Ogaden, let alone give them independence.

In

2005, Ethiopia proposed peace talks with ONLF, which the rebel group

accepted on the condition that talks be held in a neutral country and

with the presence of a neutral mediator from the international

community. The talks broke down due to Ethiopia's insistence that the

two parties meet without an arbitrator and held in countries closely

allied in the Horn of Africa. ONLF became a part of the Alliance for

freedom and democracy on May 21st 2006, fighting occurred alongside OLF

and smaller rebel groups operating in the North like TPDM.

Again

in 2006, the Meles government, with the full support of US and UK

governments, has vowed to crush the ONLF rebellion once and for all,

reinforcing the 15 thousand permanent men garrisoned in Ogadenia with a

further: 25 thousand troops, jet fighters, armored cars and some

helicopters. Between February and July 2006, the army tried to destroy

the rebellion, but failed completely, losing thousands of troops in the

process. The ONLF remained undefeated. Why did the government, with

such an overwhelming force managed to fail in its plan? They didn’t

face more than 5 to 7 thousand ONLF troops through out the region. The

answer to this is complex. Above all the ONLF’s strong support base

with the local civilian population is key. The systematic brutalization

of Ogaden civilians, and the lack of military discipline and cohesion

within government troops is another reason they weren’t defeated.

Lastly, there were totally inadequate strategies and tactics employed

against the rebels.

Indeed,

the government has found itself in a sticky spot. Its 250 thousand men

army is ill equipped to fight a war on many fronts: against the five

active rebel groups operating within Ethiopia’s border, the perpetual

tensions on the Eritrean border, and now the rise of Islam in Somalia.

Furthermore, its ranks are racked with desertion, and lack of

discipline due to the internal ethnic strife, which reigns from within

its units.

Meles

has given key positions to his own ethnic kin, the Tigray, both in the

government, and in the army, making his policies unpopular among lesser

Ethnic groups fighting alongside the Tigrays. The officer corps is

overwhelmingly from Tigray “terroir”, leaving other ethnic groups less

attractive positions within the army. Therefore, blocking any

possibilities for them to go up the ladder, the officer corps often

uses same ethnic groups to fight each other, pitting Oromos against

Oromos, or Sidamas against Sidamas. The poorly led Oromo, Amhara

soldier is sometimes forced to desert, finding it unbearable to kill

his own kin. As a consequence, a non-negligible amount of government

soldiers desert their unit to escape the grueling reality of the Ogaden

front.

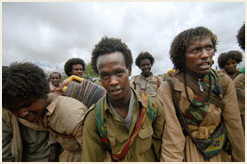

This

is the case of Thomas Gin Ernest an ethnic Hadiyan from Southern

Ethiopia, drafted by force into Meles’s army, who decided after serving

for six years to desert with a few others to the ONLF. “During our walk

to ONLF lines, half of our party changed their minds and returned to

the military camp. They were shot for treason soon after” He says this

happy to have made the right choice. When captured, Mr. Gin Ernest was

given some money so he can go home to his family and be reunited. By

treating the prisoners with respect and dignity, the rebels attract

more allies to their cause.

More

importantly, government forces have created their own monster by using

terror tactics against the local population. The government’s military

forces are known to use violence and killings against locals Ogadens.

These procedures show how Meles’s forces underestimate their enemy.

Soldiers will usually enter a village to look for potential ONLF

rebels, helpers and sympathizers pick people randomly. In essence,

Ogadens sympathize with the struggle and contribute to it, either by

joining the fighting units, or supplying them with food, water, and

guns, making them all traitors to an angry eye.

Also,

many civilians have experienced repeated violence, either personally,

or a relative. Alimo Ahment, a 24-year-old Ogaden woman, has a common

story to tell. She joined up like so many before her, because her

relatives were accused of helping the ONLF, her father was put to jail

and tortured for three months These kinds of terror tactics has had the

exact opposite results than those expected by the government: Thus, it

has increased the number of Ogadens wanting to join up with the ONLF in

ranks, and hatred against the government persists within the Ogaden

population--creating an entire new generation of freedom fighters in

the region.

The

widespread tortures, imprisonment, and killings in the region, has seen

thousands of students and locals put in jail. It is said that in the

main town of Jijiga where 20 thousand souls reside, 10% are currently

in military camps or local jails. Most of them are accused of helping

the ONLF. Many are put in confinement without trial for a minimum of

three months, which is the regular torture period, unless the prisoner

is rich enough to pay a bribe. Tortures are a daily reality and a

well-orchestrated practice. It starts at 6AM when guards grab the

prisoner into a small room, or sometimes an unusable bathroom. There,

the interrogation begins, with the simple question. If the prisoner is

part of the ONLF organization, and each time the answer is no, he or

she is beaten, electrocuted, or raped if the prisoner is a woman. This

torture is repeated twice a day for four hours each time. Survivors

have recorded extreme examples of pregnant women being tortured.

Shamaad

Wali, a 29 year ONLF female fighter recalls: “During my time in prison,

I remember the guards throwing in an eight month pregnant woman. They

repeatedly beat her until she gave birth, but the baby was already

dead. They just threw it away like garbage”. She says with tears in her

eyes. The government of course denies such claims, but in each village

such stories of tortures and killings are quite common and widespread.

Thirdly,

and lastly, government forces have failed to contain the rebellion,

which has gained in strength and confidence. On the ground, the heavily

burdened Ethiopian soldiers are not able to catch or kill large numbers

of ONLF troopers, who operate in small band using hit and run tactics;

a pretty common problem for a conventional force. The ONLF has been

able to keep the initiative, attacking on their terms, ambushing

reinforcing convoys, infantry columns, and villages held by enemy

forces. Ethiopian forces lose thousands of troops each year due to

desertions and ONLF attacks. To be sent to Ogadenia is considered by

soldiers as a punishment. Prisoners all agree that fighting the Ogadens

is the worst enemy they can encounter in Ethiopia. Known for their

warlike behavior and fighting skills, they are waging an efficient

insurgency in Ogadenia. Governmental troops do not control the land or

the local population.

For

ONLF cadre, victory is now within reach. From the rebel’s point of

view, the situation in Addis is quickly becoming unsustainable,

suggesting a partition within the country, due to the rise of ethnic

separatism. To put it in one of the commander’s words: “We started in

1994 with less than one hundred soldiers, and now look at us with seven

thousand freedom fighters willing to fight and die for the liberation

of our people,” says proudly the 50-year-old veteran commander. As it

is true that Mr. Meles’s government is fighting on many fronts, and his

army cannot defeat these various rebellions throughout the country.

Powerful Western allies, such as the United Kingdom, provide him with

weapons and money to sustain the war effort, back him; while US funding

also contribute to fight against terrorism in Ethiopia and contain

Somalia’s Islamic rise. However, it is well established that no

terrorist operates in Ethiopia, but for many of his allies in the West,

Ethiopia is seen as a Christian state with common values. This can

block the spread of Islam in East Africa. This kind of Western

strategies and political thought will surely continue to block any

attempts by rebels to challenge the government, and its military

institutions leading to their replacement.

|