Section Four

The Year in Disasters 1997

Chapter 8

Sanctions, as the former United States President Woodrow Wilson put it, "provide a peaceful, silent and deadly remedy," a form of unarmed warfare. Full economic sanctions have been applied to Iraq for over seven years now in an attempt by the international community to persuade its government to abide by United Nations (UN) resolutions and renounce all association with weapons of mass destruction.

But today, with the weapons issue still not resolved, many - humanitarian agencies and governments alike - are questioning both the effectiveness and efficiency of economic sanctions.

One of the basic tenets of the laws of war makes the distinction between the combatant and the civilian. The civilian should not be a target. Weapons should be designed and used so that they can be targeted at the combatants and avoid unduly harming civilians. But economic sanctions are proving to be no Cruise missile. Practice has shown that they are not surgical strikes but extraordinarily messy weapons, the economic equivalent of blanket bombing.

In Iraq, the welfare of the most vulnerable is inextricably linked to the political and economic decisions that surround the imposition, or relaxing, of UN sanctions. To address the growing malnutrition and public health crisis, to assist those in need, humanitarian agencies have to tread a wary path through this minefield, addressing the effects of crisis whilst steering clear of being drawn into, or implicated in, the political debate over root causes.

Sanctions and malnutrition

In the back room of a Baghdad hospital, the Iraqi Red Crescent runs one of its special feeding posts targeted at the most vulnerable children in the capital. The mothers who leave the hospital with bags of rice and bottles of oil may themselves be hungry: many live on far less than US$ 1-a-day World Bank- defined world poverty level. As they leave the hospital, the women pass by as the young rich from a nearby private college gather at a cafe; begging is unthinkable as each group passes the other. Such contrasts are common currency in Iraq today, giving a hint of the complexity of the relationship between the political effectiveness and the humanitarian efficiency of sanctions.

Although vital to restore a malnourished child to its full weight, extra rations are not a solution to Iraq's crisis, but a temporary treatment of the symptoms of this form of "manmade" disaster: an embargo that may well have killed hundreds of thousands of children - 5,500 per month by Iraqi government estimates - and has been slowly pushing almost an entire country into impoverishment since the first UN Security Council resolution was passed in August 1990.

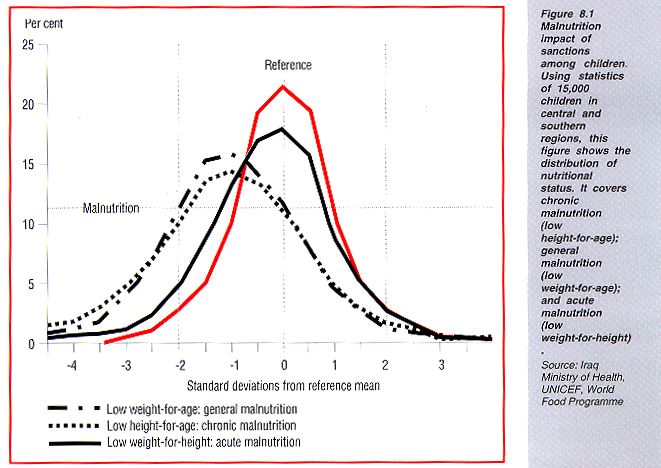

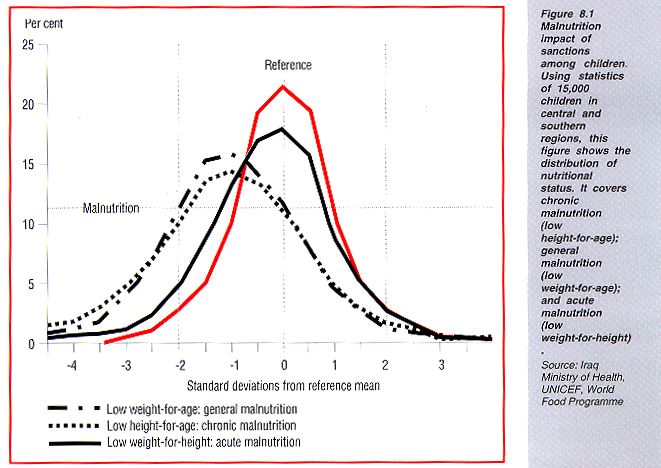

A survey by UNICEF and the Iraqi government in 1997 suggested that 31 per cent - equivalent to 960,000 children - were suffering from either mild, moderate or acute chronic malnutrition, up from 18 per cent in the already worsening situation of 1991. Eleven per cent - around 340,000 children - had acute malnutrition, up from 3 per cent; and 26 per cent were underweight, against 9 per cent in 1991.

Iraq's eighth year of sanctions ushered in months of controversy over UN weapons inspectors, threats of renewed international conflict, and the negotiation mission to Baghdad by UN Secretary- General Kofi Annan. Meanwhile, despite the stop-start nature of the multi-billion dollar oil-for-food deal, millions remained poor, hungry or displaced, with large numbers of additional deaths through disease, and high levels of child malnutrition.

Oil-for-food

The oil-for-food operation delivered its first food in April 1997. This was six years after it was first mooted, two years after the Security Council approved resolution 986, allowing Iraq to sell $2 billion of oil every six months and use the money to buy food, medicines and other goods under the tight control of a UN Sanctions Committee, and almost a year after the details had finally been agreed with Baghdad in June 1996.

Despite the years of discussion and planning, it was not until August 1997 that the first full monthly ration under resolution 986 was actually delivered. By early in 1998, a complete ration had been achieved only twice more, in September 1997 and March 1998, while the extent of the emergency in nutrition and health had been highlighted in new UN studies.

On paper, the new food basket of 2,030 kcal and 47 grams of protein per person per day appeared a big improvement over the monthly government ration introduced under sanctions, which had varied from a high of 1,705 kcal to a low of 1,093 kcal. But the new ration was still below minimum Iraqi needs, estimated at 2,600 kcal per person per day by a UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/World Food Programme (WFP) mission to Iraq in 1997.

There was swift criticism of the ration as too low in energy, vitamins, minerals and protein, and insufficient to prevent continued malnutrition, even if all the food arrived and was distributed efficiently. The FAO/WFP mission called it "inadequate and unbalanced". Other food sources, from aid agency feeding programmes to black-market purchases, would be needed to sustain a healthy population.

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan recognized these shortcomings. Before heading for Baghdad in early 1998, he proposed raising the value of the oil-for-food deal to $5.2 billion every six months - allowing, after UN and reparation deductions, $3.4 billion for humanitarian needs - and overhauling much of the Sanctions Committee's structure and systems.

In part, the extra money was needed to raise the ration to 2,463 kcal and 63.6 grams of vegetable and animal protein, including the addition of cheese and full-cream powdered milk. Over six months, this would mean increasing food spending by $23 to $60 per capita; overall food spending would increase by $619 million to $1.5 billion. Pilot projects would also encourage egg and chicken production for a market low in animal protein.

In addition to extra food, the proposal acknowledged the complexity and depth of the wider crisis, since it would bring significant increases in the money available for many other sectors needing support, from restoring power supplies and repairing water and sanitation systems to improving agriculture, rebuilding schools, assisting resettlement, expanding de-mining and boosting spending on drugs and hospitals.

But that would depend on Iraq pumping far more oil. Baghdad immediately suggested that $4 billion was the limit if oil prices remained low. At 1997 prices, the $55-a-barrel rates of the early 1980s sank to $20 in January 1997 and hit $11.27 in early 1998. Oil producer countries feared greater Iraqi output would depress prices still further.

The oil-for-food deal brought complex new systems for contracts and sanctions approval. In late 1997, the UN Office of the Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq (UNOHCI) estimated that, on average, in the first phase of the oil-for-food deal, it was taking 66 days to have a food contract approved by the Sanctions Committee system, 59 days for the food to be delivered, and seven to make it available for distribution to Iraqi beneficiaries.

The food and other supplies have arrived through four entry points: Al-Walid opposite Al-Tenf in Syria; the Iraqi Gulf port Umm Qasr; Treibil on the Jordanian border; and Kbabour on Turkish border. By 2 April 1998, 5 million metric tons of foodstuffs had been delivered to Iraq. Through government warehouses, silos and distribution points, supplies are delivered to more than 50,000 retail agents.

Each agent distributes rations every month to hundreds of families, with a nominal fee imposed on each recipient to cover transportation and administrative costs. The food basket includes wheat flour, rice, sugar, oil, pulses, tea, salt, soap, detergent and - for families with children under one - infant formula. Food rations typically last for an average of 20 days in the month, and so require significant supplementing from wages, trading, selling possessions, or community and family networks.

Siege economy

Be it $4 billion or $5.2 billion, Iraq could easily absorb additional funds, for the same reasons that made it look so vulnerable to economic sanctions back in 1990. It is not a low-income rural country of small farmers able to eke out an existence from the land if necessary. It is an urban country and had an economically buoyant economy. Iraq claims that sanctions have denied its growing oil-based economy some $120 billion in revenues since 1990.

In the past, that income paid for $2 to $3 billion of annual food imports to meet two-thirds of its needs, thousands of foreign workers, $30 per person a year drug supplies, cheap or free health care, an effective education system, and plenty of jobs in ministries, military forces and state-backed enterprises. In this urbanized society, three-quarters of the 22 million population were dependent on the complex lifelines of towns and cities, from electrical power to piped water.

Since 1990, sanctions have had a profound impact, creating for many a siege economy of price inflation, currency devaluation, soaring unemployment and a widening income gap. Most Iraqis have been gradually selling off all their possessions - from jewellery to furniture and television sets - to survive. By 1995, falling incomes and rising prices were estimated to have reduced earnings to only 5 per cent of their pre-sanctions value in food purchasing terms.

Sanctions have been particularly tough on Iraq's many state employees and others on fixed incomes, and the middle class have seen both income and capital disappear.

While state staff, from civil servants to teachers, have found extra work elsewhere, if only becoming street vendors, wider changes initiated by the Iraqi government have been encouraging a larger role for the private sector in a state-led economy. Iraq has been selling state assets, offering shares in state enterprises to staff, and allowing new private businesses, from hospitals to banks, to emerge.

For Iraqis, some forms of private enterprise may be more welcome (smuggling of all kinds for example, including oil) than others (begging, prostitution, robbery), but all have grown despite often tough punishments for offenders. A worrying side effect of this trend has been that traditional community leaders no", play a lesser role. The black-market aristocracy that has emerged will inevitably have repercussions on the form of civic society that eventually emerges in Iraq.

If millions are not to be forced into endemic poverty or to become refugees, rising food prices and limited stocks make rationing vital. Aid agencies have praised the Iraqi government's achievements in creating a well-run national rationing system, which has helped to ensure that, despite delays and shortfalls, the vast majority of the Iraqi population has had access to at least a portion of the minimal food basket since sanctions were imposed.

Establishing and managing the ration system has also had the effect of reinforcing the government's authority, as it registered families across the country, and fostering its legitimacy when it managed to deliver a small but equitable food package every month for more than five years to millions of people without large-scale international support.

Coping with sanctions

Rations have kept the maJority of people alive as they gradually converted their assets into cash, but a series of studies involving UN agencies and Iraqi government departments since the start of sanctions have all showed serious health problems that are far worse than regional averages. By 1997, the Iraqi government was claiming that up to 5,500 under-five deaths a month were the result of sanctions. There was a clear rising trend of malnutrition among children under five, although specific figures have varied widely.

In part, that is because of the three rather different forms of malnutrition

being measured:

· chronic malnutrition or stunting involves low height-for-age

and comes from long-term poor conditions, health and feeding;

· acute malnutrition or wasting is low weight-for-height and shows more immediate problems, such as diarrhoea or other disease, or sudden reduction in feeding; and

· general malnutrition or underweight is low weight-for-age and can result from either or both other conditions.

In 1997, the FAO/WFP mission to Iraq conducted two rapid nutrition surveys in and around Baghdad. They arrived at rather lower ranges of figures, with chronic malnutrition put at 16 to 27 per cent, acute at 3 to 5 per cent (or 93,000 to 155,000) and underweight at 11 to 18 per cent. However, they felt the higher figures were probably more representative of Iraq as a whole since capital cities, for both political and logistical reasons, usually have preferential access to food. They also found that among those under 26 years of age, 2.5 per cent of men and 16 per cent women were undernourished.

The mission, led by Professor Peter Pellett of the Department of Nutrition at the University of Massachusetts, confirmed the known correlations between the education levels of mothers and the condition of children, with a far lower prevalence of malnutrition among the children of women with college or university degrees. It also showed the connection between bouts of diarrhoea and both chronic and general malnutrition, and highlighted the need to fortify food supplies with additional nutrients, a cost-effective process for bulk supplies.

This confirmed the views of many aid observers that food availability is but one factor in determining the overall nutritional status of children. Illustrative of this is the degenerated state of Iraq's water supply and sanitation systems, particularly in urban areas, which has lead to an increase in water- borne diseases and the incidence of diarrhoea, both of which directly effect nutritional levels.

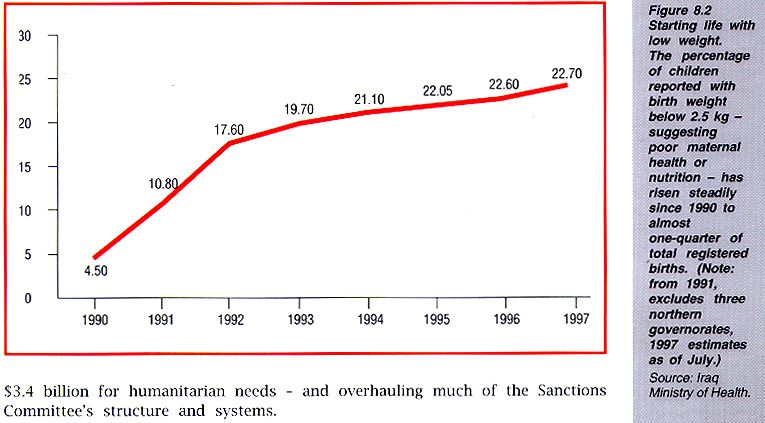

Another illustration of the complexity of linking cause and effect in malnutrition has been the rising government figures for the proportion of low birthweight babies. From 4 per cent in 1990, the figure for babies born under 2.5 kg has reached around a quarter of registered births today. This may be due to maternal malnutrition or more attributable to the 70 per cent of Iraqi women who suffer from anaemia. Malnutrition and anaemia are closely linked and, although anaemia has traditionally been a concern in Iraq, the figure of 70 per cent is exceptionally high.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that many of these Iraqi children will not catch up in their physical or mental development, laying the foundation for continued long-term health problems in the country.

Although reliable figures are scarce, both infant and under-five mortality rates seem to have risen sharply. One factor may be the way the many positive aspects of breastfeeding - from nutrition to birth spacing and even cost - are not being adequately promoted. This is particularly crucial in Iraq - an urbanized, developed economy where breastfeeding was in decline. Now, with much of its public health infrastructure fallen into decay, old pre-war, pre-sanctions practices need to be changed. The encouragement of, and education on, breastfeeding is a priority for child health programmes.

The standard ration - including that being brought in under UN Security Council resolution 986 - has offered infant formula to all families with children under one year. In the past, three-quarters preferred to take an extra adult ration instead, but that option was removed in May 1997. The FAO/WFP mission in 1997 commented on the lack of breastfeeding seen among the mothers of the malnourished, and urged that the ration choice be reinstated.

Health systems failure

Sanctions, following on the effects of war, have seriously hampered the Iraqi health care system in many ways: cutting imports of drugs and equipment; slowing resumption of local drugs production; causing an exit of foreign medical and nursing staff; and restricting contacts between Iraqi doctors and outside experts. Iraqi spending on medicines fell to about $3 per capita in 1995/1996 but recovered to $16 in 1997, about half of the pre-sanctions level of local production and $500 million in imports.

The 986 deal was due to bring in $210 million of medical supplies every six months, but serious delays allowed widespread shortages of antibiotics, analgesics, anesthetics and laboratory test materials to continue. Many diseases re-emerged during the embargo, especially those linked to the damaged water and sanitation systems, from cholera to typhoid and malaria.

There were UN proposals to more than triple health spending to $770 million every six months from an expanded oil-for-food deal, plus a one-off $449 million to re-establish systems and facilities, such as the vaccines cold chain. But even if supplies of drugs and equipment improve, problems will remain in staffing health facilities. Many of Iraq's former health care professionals were expatriates; almost all of whom have now left the country. Many Iraqi doctors are now working overseas, while Iraqi women have always shunned nursing as a career. The focus on physical disease also means that not enough attention has been paid to very real needs in mental health. An increasing number of psychological problems have been seen in war widows, orphans and those forced into poverty by sanctions.

There are plenty of other sectors needing money, from education - where once-high primary school enrolment rates have fallen to 75 per cent or less - to de-mining, resettlement, and agriculture, where output has continued to fall, because of problems over the supply of seeds, equipment, fertilizer, pesticides and water from irrigation systems.

Crises loom for Iraq's power, water and sanitation systems. They are linked together in the country's flat landscape, where pumping is essential and the restoration of water treatment desperately required. For many millions, contaminated water - from broken mains or a local river - is the only option. The un has advocated for an eight-fold increase in the spending on water and sanitation, from $44 million to $321 million. It has suggested an entirely new multi-billion dollar strategy to deal with the bulk of Iraq's power restoration.

The scale of Iraq's needs from both the impact of war and the effects of sanctions has been put in the hundreds of billions of dollars, suggesting that even when the embargo is lifted, it will take the country and its people years to fully recover. Much of the infrastructure for the health system will need to be completely overhauled or replaced. Many health care facilities were built in the early 1980s before the war with Iran, the Gulf war and the imposition of sanctions. They are now out of date and virtually obsolete.

It seems unlikely that anyone expected such a costly and slow scenario in 1990, when sanctions started and war was being prepared. Perhaps it was the ambitious optimism of a time of great change, when many thought far more would be possible in diplomacy, backed up by forces freed from stalemate.

Sanctions have expanded as a tool of both national foreign policy and international coercion since the end of the Cold War, during which such measures could expect superpower veto or evasion. The other international tool that grew after the Cold War - military intervention - has lost a lot of its attraction as casualty figures and the complexity and open-ended nature of peacekeeping operations deter military commitment. Sanctions had been seen as a useful non-violent alternative, but Iraq and other experiences may also be forcing a rethink here.

Whatever its political effectiveness, the success or failure of which is for others to judge, the sanctions regime has clearly had serious consequences for the ordinary Iraqi population: forcing many into poverty, destroying human dignity and taking lives.

The long-awaited oil-for-food response to the crisis that sanctions created has not has the necessary impact either, especially for the most vulnerable. As Kofi Annan concluded in December 1997, it was insufficient "to address, even as a temporary measure, all the humanitarian needs of the Iraqi people", which led to his plans for a "systematic review of the whole process of contracting, processing of applications, approvals, procurement and shipment and distribution".

Aid lessons

The unprecedented nature of the experiments of oil-for-food and comprehensive embargo being carried out in Iraq are offering important lessons for the future. Some are fairly direct. There is the challenge of understanding the real consequences of sanctions through baseline statistics, detailed surveys and regional knowledge so they can be managed as effectively as possible within very limited resources.

There is also the need to go beyond the obvious - lack of food as a cause of malnutrition - to deeper factors - sanitation in one situation, for example, education in another - that might suggest the solution is not only better rations but also a ne", water main or effective use of radio to promote breastfeeding.

Equally important is the ever-present risk to agency independence and impartiality when operating in a highly political environment, where one side in the political confrontation also controls the majority of the resources available for supplying humanitarian assistance. Aid agencies operating in Iraq need to apply the same clear and uncompromising ground-rules to their work as they would in another situation where humanitarian aid is provided.

Finally, there is the crucial recognition by the very same governments

that have agreed on the imposition of sanctions through the appropriate

international systems, that humanitarian organizations have a right to

take action to assist the most vulnerable individuals - the unintended

victims of the sanctions. Aid agencies have learnt that they need to lobby

governments hard to get the message across that humanitarian organizations

such as the Red Cross/Red Crescent offer a neutral and impartial channel

for well-targeted humanitarian assistance. Governments can choose to support

these agencies without compromising their political objeCtiveS. Through

this crucial recognition and principled support for the right to humanitarian

aid, many hundreds of thousands of young children, women and old people

have been assisted in Iraq, and in other countries under sanctions.

Chapter 8 Sources, references and further reading

Dario, Bernard. A Preliminary Evaluation of Children's Nutritional Conditions in the Central Region of Iraq. Nutrition Research Programme, UN Development Programme, November 1989.

Graham-Brown, Sarah. "The Iraq Sanctions Dilemma; Intervention, Sovereignty and Responsibility" in Middle East Report, March-April 1995, London.

Haass, Richard N. "Sanctioning Madness" in Foreign Affairs. November/December 1997, Washington DC.

Hoskins, Eric. The Impact of Sanctions; A Study of Unicef's Perspective. New York: United Nations Children's Fund, 1998.

Hoskins, Eric. "The Humanitarian Impact of Economic Sanctions and Wae " in Political Gain and Civilian Pain. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997.

International Committee of the Red Cross. Water in Iraq. Geneva: ICRC, 1996.

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Iraq Relief Operation. Situation Reports. Geneva, 1997.

Iraqi Economists Association. Human Development Report 1995. Baghdad.

Office of the UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq. The Oil-for-Food Operation. Baghdad, 1997.

Royal Institute of International Affairs. "Saddam's Bazaar" in The World Today, March 1998, London.

UN Department of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Report 1997. New York: UNDHA, 1997.

UNICEF. The 1996 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey; A Survey to Assess the Situation of Children and Women in Iraq. Baghdad: UNICEF, October 1997.

UNICEF. Nutritional Status Survey at Primary Health Centers During Polio National Immunization Days in Iraq, April 1997. Baghdad: UNICEF, 1997.

UNICEF. Monthly Situation Reports. Baghdad.

ArabNet:

http://www.arab.net/iraq/iraq-contents.htmI

FAO/WFP Food Supply and Nutrition Assessment Mission to Iraq:

http://www.tao.org/GIEWS/english/alertes/srirq997.htm

ICRC:

http://www.icrc.org

International Federation:

http://www.ifrc.org

Iraqnet:

http://www.iraq.net/

Box 8.1 Eight years under embargo, from 661 to the oil-for-food 986

Sanctions began in August 1990 with UN Security Council resolution 661 barring all imports and exports except essential food and medicines as part of international pressure for Iraqi troops to leave Kuwait.

Eight further Security Council resolutions were passed from 1990 to 1992, covering sea and air blockades, the ceasefire, Iraqi assets overseas and two on the sale of oil for food.

In April 1995, with the situation of ordinary Iraqis worsening and surveys by UN agencies revealing increasing hunger and illness, the Security Council passed resolution 986 allowing the sale of $2 billion of Iraqi oil every six months and the purchase of food and medicines, as well as spare parts and supplies for the electricity, water, sanitation, agriculture and education sectors.

A memorandum of understanding on resolution 986 signed by the UN and Iraq in May 1996 set out how each $2 billion should be divided: $1.32 billion for "humanitarian" supplies; $600 million into a compensation fund for those affected by the Kuwait occupation; $44 million for the administrative costs of UN aid operations; and $15 million for UN arms inspectors.

A range of geographical and multi-disciplinary UN observers across the country assess supplies, monitor transportation, interview beneficiaries, and check the records of hospitals, warehouses and the tens of thousands of distribution agents.

UN agencies have a sectoral role, tracking supplies and gathering data, such as WHO for medical supplies; WFP in food distribution; UNICEF on nutrition and immunization; FAO for agriculture and markets; Habitat in shelter; the UN Development Programme with electricity generation and transmission.

The first supplies paid for through resolution 986 arrived in March

1997, and the first full enhanced food ration was distributed in August

1997.

Box 8.2 Scenes from a sanctions siege

The combination of sanctions and "no-fly" zones in both north and south mean that while UN staff arrive on special flights, the road from Amman in Jordan is the main route into Baghdad for all other aid workers. It's a journey that gives the first indications of the unique blend of challenges, opportunities and contradictions in a country under siege.

Even on the fast highway, it takes a long hot day to drive the 850 km across the stony desert, past the occasional wreck and mangled barriers that are evidence of local driving risks. To the road dangers and distances of a big country can be added long delays and paperwork: the inevitable hour of queues and forms - not forgetting a mandatory blood test if you lack a letter certifying your HIV status - at the border crossing.

Sanctions have added their sometimes surprising twist to the situation of aid staff living and working in a divided nation which is emerging all too slowly from two wars, where conflict continues and millions are malnourished, sick or displaced.

This is an oil-producer under embargo, whose economy continues to contract under sanctions and where electricity is limited. Hunger, impoverishment and malnutrition abound. Millions have become steadily poorer trying to survive on inadequate daily rations by selling their jewellery, TV sets, furniture and spare clothes. All true, but no disaster impoverishes everyone.

At the border, anything on four wheels that can be stuffed with trade goods fills up in Iraq with petrol so cheap a tankful costs a few cents. Baghdad can be well-lit, jammed with traffic and noisily busy 24 hours a day, with extensive repairs leaving few signs of air-raid damage. Crowded street markets are full of consumer items, food stalls are piled high with vegetables, and among the growing number of newly refurbished shops are plenty of hamburger bars and ice-cream parlours.

Since the imposition of sanctions in 1990, the 1991 Gulf war and introduction of the mainly Kurdish "safe havens" in three northern governorates, Iraq has experienced an ebb and flow of aid agencies assisting its 22 million people.

Many arrived to work in the safe havens, but years of factional fighting and international conflict have prompted some to leave, while more recently the small number of agencies arriving to work in the 15 central and southern governorates has begun to rise.

From Baghdad, most agencies - from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies to the Middle East Council of Churches - work in partnership with the Iraqi Red Crescent Society, which was founded in the 1930s and has a nationwide network of offices and staff.

As sanctions manager and monitor, the UN in Iraq has the world's only self-sustaining UN operation. Many of its bills are the first deductions from the multi-billion dollar oil-for-food deal allowing Iraq to buy so-called "humanitarian" goods under tight controls.

With so many roles within one set of initials - investigation, diplomatic, humanitarian, negotiation - UN aid staff live at the centre of the Iraq contradiction: sanctions as war by another means are clearly doing significant damage to civilians, but the response is a less than adequate supply of food and drugs, often delivered late.

Working conditions are not easy. Unexplained delays, cumbersome paperwork and poor communications slow down operations. In the north, the on-off conflicts mean curfews and insecurity are common, with occasional attacks on aid convoys.

Inevitably in Iraq, security of all sorts is tight. Foreigners need formal permission for many actions - travel beyond the capital, importing communications equipment, living outside the few designated hotels - that would usually present fewer problems elsewhere.

Most foreigners are on short contracts - one year is a long time in Iraq - which has its own impact on the continuity of operations. But there are also some positive elements to Iraq's grinding problems.

Few countries could have organized such a fair rationing system. The

road network and cheap fuel make travelling easier than in many other disaster

zones, and the high level of education and skills available within the

Iraqi population makes local staff a key resource in the aid effort.

Box 8.3 Northern needs in the conflict-hit havens with 500,000 displaced

The northern three of Iraq's 18 governorates are still under UN sanctions yet have separate systems of administration as a result of the exodus of Kurds following the Gulf war and the creation of "safe havens" under a no-fly zone to assist their return.

Extensive fighting in the Kurdish-controlled governorates of Erbil, Dohuk and Sulaimaniyah have left these havens rather less than safe, with around 500,000 displaced people in early 1998.

Many of the displaced cannot return to their villages because their homes have been destroyed or political changes have made going back impossible. Living in abandoned military camps, damaged public buildings, pre-fabricated houses or tents, the displaced are left even more vulnerable because they lack land.

Even for the settled, conditions in the mountainous north can be hard, with tough winters, inadequate housing and sanitation, poor electricity supplies, lack of fuel, limited communications, and high unemployment. Agriculture has suffered from the lack of fertilizers and pesticides.

Despite frequent ceasefires in this volatile situation, the conflicts have increased the needs while disrupting humanitarian operations. Aid agency convoys have been fired on, or had vehicles seized, forcing the use of guards.

As well as the same ration as the central and southern regions - delivered by the UN - the north has a supplementary feeding programme for around 250,000 vulnerable people, including pregnant women and malnourished children, supported by WFP.

Although cut off from traditional markets in the rest of Iraq, the north probably benefits from greater trade through porous international borders. It also has significantly higher per capita aid spending from the 986 oil-for-food funds, according to UNOHCI.

Perhaps linked to this, the nutritional status of children in the three northern governorates has been a little better than those in the central and southern region.

There are an estimated 10 to 20 million mines in the north, especially along the border with Iran. In early 1998, the UN began a $4.5 million mine clearance programme in the three northern governorates, financed from the oil-for-food agreement, which will train 120 supervisors, team- leaders, medics and de-miners.