Cluster Bombs

Regardless of its type or purpose, dropped ordnance is dispensed

or dropped from an aircraft. Dropped ordnance is divided into three

subgroups: bombs; dispensers, which contain submunitions; and

submunitions.

DISPENSERS

Dispensers may be classified as another type of dropped ordnance. Like

bombs, they are carried by aircraft. Their payload, however, is smaller

ordnance called submunitions. Dispensers come in a variety of shapes

and sizes depending on the payload inside. Some dispensers are

reusable, and some are one-time-use items.

Dropped dispensers fall away from the aircraft

and are stabilized in flight by fin assemblies. Dropped dispensers may

be in one piece or in multiple pieces. All dropped dispensers use

either mechanical time or proximity fuzing. These fuzes allow the

payload to be dispersed at a predetermined height above the target.

Multiple-piece dispensers open up and disperse their payload when the

fuze functions. Single-piece dispensers eject their payload out of

ports or holes in the body when the fuze functions.

Dropped dispensers fall away from the aircraft

and are stabilized in flight by fin assemblies. Dropped dispensers may

be in one piece or in multiple pieces. All dropped dispensers use

either mechanical time or proximity fuzing. These fuzes allow the

payload to be dispersed at a predetermined height above the target.

Multiple-piece dispensers open up and disperse their payload when the

fuze functions. Single-piece dispensers eject their payload out of

ports or holes in the body when the fuze functions.

Attached dispensers stay attached to the aircraft and can be reloaded and used again. Their payload is dispersed out the

rear or from the bottom of the dispenser.

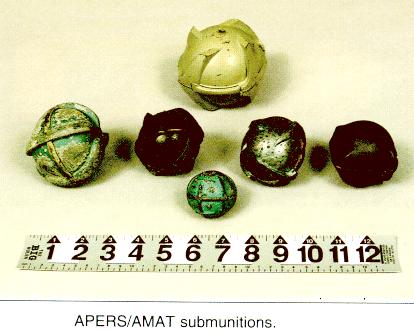

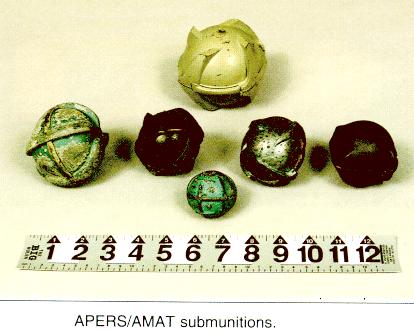

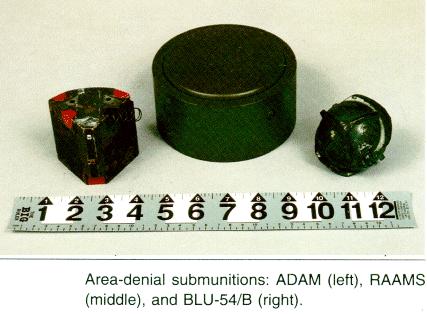

Submunitions are classified as either bomblets,

grenades, or mines. They are small explosive-filled or chemical-filled

items designed for saturation coverage of a large area. They may be

antipersonnel (APERS), antimateriel (AMAT), antitank (AT), dual-purpose

(DP), incendiary, or chemical. Submunitions may be spread by

dispensers, missiles, rockets, or projectiles. Each of these delivery

systems disperses its payload of submunitions while still in flight,

and the

submunitions drop over the target. On the battlefield, submunitions are

widely used in both offensive and defensive missions. Submunitions are used to destroy an

enemy in place (impact) or to slow or prevent enemy movement away from

or through an area (area denial). Impact submunitions go off when they

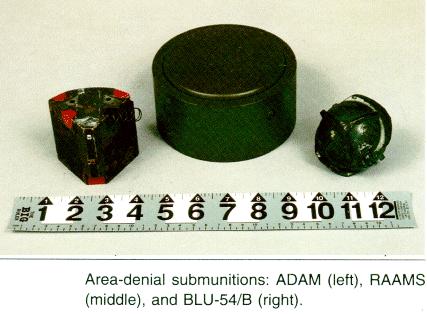

hit the ground. Area-denial submunitions, including

FASCAM, have a limited active life and self-destruct after their active

life has expired. The major difference between scatterable mines and

placed mines is that the scatterable mines land on the surface and can

be seen. Placed mines may be hidden or buried under the ground and

usually cannot be seen.

Submunitions are classified as either bomblets,

grenades, or mines. They are small explosive-filled or chemical-filled

items designed for saturation coverage of a large area. They may be

antipersonnel (APERS), antimateriel (AMAT), antitank (AT), dual-purpose

(DP), incendiary, or chemical. Submunitions may be spread by

dispensers, missiles, rockets, or projectiles. Each of these delivery

systems disperses its payload of submunitions while still in flight,

and the

submunitions drop over the target. On the battlefield, submunitions are

widely used in both offensive and defensive missions. Submunitions are used to destroy an

enemy in place (impact) or to slow or prevent enemy movement away from

or through an area (area denial). Impact submunitions go off when they

hit the ground. Area-denial submunitions, including

FASCAM, have a limited active life and self-destruct after their active

life has expired. The major difference between scatterable mines and

placed mines is that the scatterable mines land on the surface and can

be seen. Placed mines may be hidden or buried under the ground and

usually cannot be seen. The ball-type submunitions are APERS. They

are very small and are delivered on known concentrations of enemy

personnel, scattered across an area. Like a land mine, it will not blow

up until pressure is put on it.

The APERS submunition can be delivered by aircraft

or by artillery. When it hits the ground, a small fragmentation ball

shoots up and detonates about 6 feet above the ground. The area-denial

APERS submunitions (FASCAM) are delivered into areas for use as mines.

When they hit the ground, trip wires kick out up to 20 feet from the

mine. All area-denial submunitions use antidisturbance fuzing with

self-destruct fuzing as a backup. The self-destruct time can vary from

a couple of hours to as long as several days.

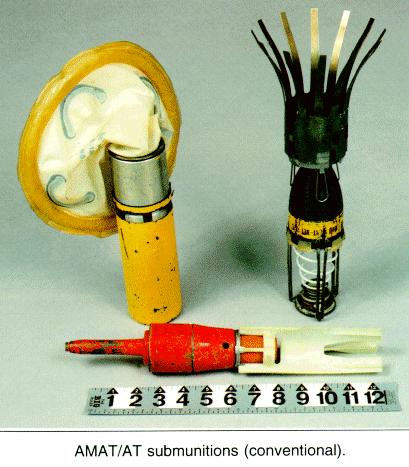

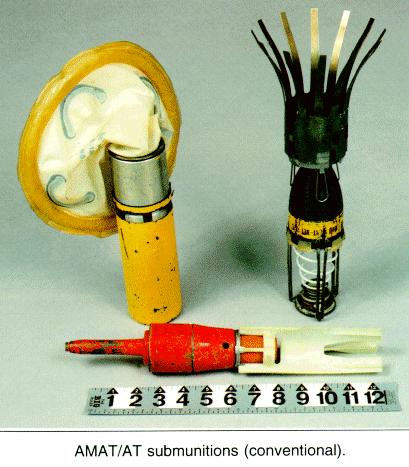

The AMAT and/or AT submunitions are designed to

destroy hard targets such as vehicles and equipment. They are dispersed

from an aircraft-dropped dispenser and function when they hit a target

or the ground. Drogue parachutes stabilize these submunitions in flight

so they hit their targets straight on. The submunitions are also used

to destroy hard targets such as vehicles and equipment. The only

difference is that the fin assembly stabilizes the submunition instead

of the drogue parachute.

AT area-denial submunitions can be delivered by

aircraft, artillery, and even some engineer vehicles. These FASCAMs all

have magnetic fuzing. They will function when they receive a signal

from metallic objects. These submunitions, similar to the APERS

area-denial submunitions, also have antidisturbance and self-destruct

fuzing. AT and APERS area-denial mines are usually found deployed

together.

Most airframes are capable of delivering a

variety of submunitions. There is no set air delivery mission profile.

The hazard area depends on the submunition, mission profile, target

type, and number of sorties. Air Force and naval air power employ

cluster bomb units (CBUs) containing submunitions that produce hazard

areas similar to MLRS/ cannon artillery submunitions. Air delivered

canisters contain varying amounts of CBUs. One CBU-58 or three CBU-87/

CBU-52 contain approximately the same number of submunitions as one

MLRS rocket with 644 submunitions. A B-52 dropping a full load of 45

CBUs (each CBU-58/CBU-71 contains 650 submunitions) may produce an

hazard area that is significantly more dense than an MLRS hazard area.

A typical F-16 flying close air support (CAS) against a point target

may drop two CBUs per aircraft per run, thus producing a very

low-density hazard area.

Saturation of unexploded submunitions has

become a characteristic of the

modern battlefield. The potential for fratricide from unexploded

ordnance [UXO] is increasing. Joint Publication 1-02 defines unexploded

explosive ordnance as “explosive

ordnance which has been primed, fused, or otherwise prepared for

action, and which has

been fired, dropped, launched, projected, or placed in such a manner as

to constitute a

hazard to operations, installations, personnel or material and remains

unexploded either

by malfunction or design or for any other cause." Although ground

forces are concerned

with all unexploded ordnance, the greatest potential for fratricide

comes from

unexploded submunitions.

Most airframes are capable of delivering a

variety of submunitions. There is no set air delivery mission profile.

The hazard area depends on the submunition, mission profile, target

type, and number of sorties. Air Force and naval air power employ

cluster bomb units (CBUs) containing submunitions that produce hazard

areas similar to MLRS/ cannon artillery submunitions. Air delivered

canisters contain varying amounts of CBUs. One CBU-58 or three CBU-87/

CBU-52 contain approximately the same number of submunitions as one

MLRS rocket with 644 submunitions. A B-52 dropping a full load of 45

CBUs (each CBU-58/CBU-71 contains 650 submunitions) may produce an

hazard area that is significantly more dense than an MLRS hazard area.

A typical F-16 flying close air support (CAS) against a point target

may drop two CBUs per aircraft per run, thus producing a very

low-density hazard area.

Saturation of unexploded submunitions has

become a characteristic of the

modern battlefield. The potential for fratricide from unexploded

ordnance [UXO] is increasing. Joint Publication 1-02 defines unexploded

explosive ordnance as “explosive

ordnance which has been primed, fused, or otherwise prepared for

action, and which has

been fired, dropped, launched, projected, or placed in such a manner as

to constitute a

hazard to operations, installations, personnel or material and remains

unexploded either

by malfunction or design or for any other cause." Although ground

forces are concerned

with all unexploded ordnance, the greatest potential for fratricide

comes from

unexploded submunitions.

Submunition function reliability requirement

is no less than 95 percent. With a 95 percent submunition function

reliability, one CBU-58 (with 650 submunitions) could produce up to 38

unexploded submunitions. A typical B-52 dropping a full load of 45

CBU-58/CBU-71, each containing 650 submunitions, could produce an

average of some 1700 unexploded sub-munitions. The numbers of

submunitions that fail to properly function and the submunitions’

dispersion determine the actual density of the hazard area.

Studies that show 40 percent of the

duds on the ground are hazardous and for each encounter with an

unexploded submunition there is a 13 percent probability of detonation.

Thus, even though an unexploded submunition is run over, kicked,

stepped on, or otherwise disturbed, and did not detonate, it is not

safe. Handling the unexploded submunition may eventually result in

arming and subsequent detonation.

http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/dumb/cluster.htm

Maintained by Webmaster

Originally

Updated Saturday, June 26, 1999 4:21:40 PM