| Security Council |

| Social & Economic Policy |

| NGOs |

| Globalization |

| Empire? |

| Iraq |

| Nations & States |

| International Justice |

| UN Financial Crisis |

| UN Reform |

| Secretary General |

| *Opinion Forum |

| Tables& Charts |

For pdf version, click here

Crude Designs:

The Rip-Off of Iraq’s Oil WealthBy Greg Muttitt

PLATFORM with Global Policy Forum,

Institute for Policy Studies (New Internationalism Project)

New Economics Foundation

Oil Change International and War on Want

November 2005

Acknowledgements

Researched and written by Greg Muttitt of PLATFORM www.carbonweb.org, with assistance from Guy Hughes and Katy Cronin of Crisis Action www.crisisaction.org.uk.

Advice on economic modelling provided by Dr Ian Rutledge of Sheffield Energy & Resources Information Services (SERIS) www.seris.co.uk

Published by PLATFORM with Global Policy Forum, Institute for Policy Studies (New Internationalism Project), New Economics Foundation, Oil Change International and War on Want - November 2005.

Design by Guy Hughes www.power-shift.org.uk. Cover design by Ishka Michocka www.lumpylemon.co.uk.

Printed by Seacourt Press on recycled paper (75% post-consumer waste) using a waterless process in compliance with ISO 14001 and EMAS.

Contents Back to top Chapters:

1 - The ultimate prize: Anglo-American interests in Gulf oil2 - Re-thinking privatisation: Production sharing agreements

3 - Pumping profits: Big Oil and the push for PSAs

4 - From Washington to Baghdad: Planning Iraq's oil future

5 - Contractual rip-off: the cost of PSAs to Iraq

Appendices:

1 - How a Production Sharing Agreement works

List of tables:

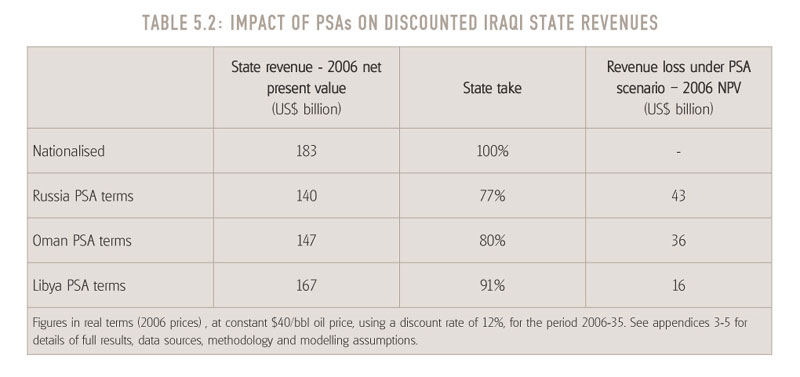

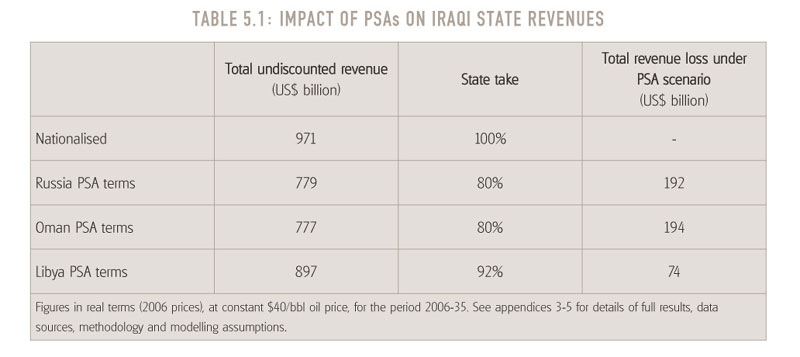

5.1 - Impact of PSAs on Iraqi state revenues5.2 - Impact of PSAs on discounted Iraqi state revenues

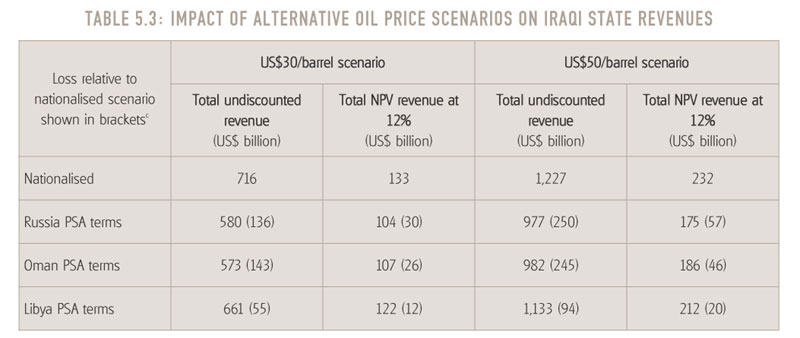

5.3 - Impact of PSAs on Iraqi revenues at different oil prices

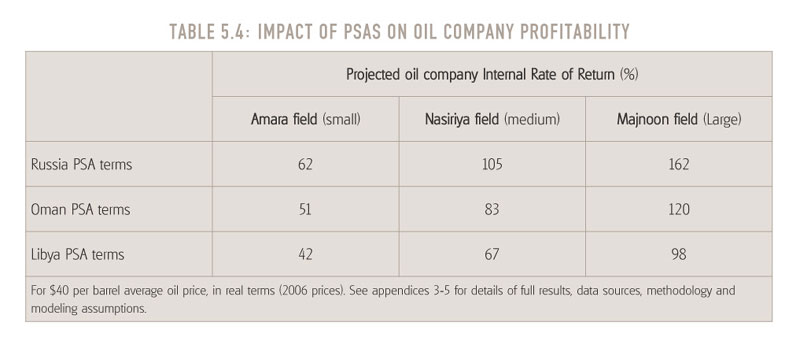

5.4 - Impact of PSAs on oil company profitability

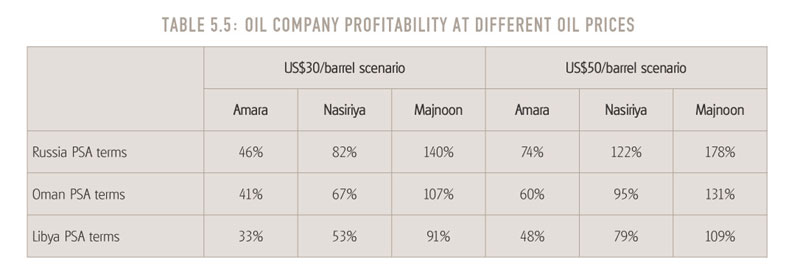

5.5 - Oil company profitability at different oil prices

Executive Summary

Back to top While the Iraqi people struggle to define their future amid political chaos and violence, the fate of their most valuable economic asset, oil, is being decided behind closed doors.

This report reveals how an oil policy with origins in the US State Department is on course to be adopted in Iraq, soon after the December elections, with no public debate and at enormous potential cost. The policy allocates the majority (1) of Iraq’s oilfields – accounting for at least 64% of the country’s oil reserves – for development by multinational oil companies.

Iraqi public opinion is strongly opposed to handing control over oil development to foreign companies. But with the active involvement of the US and British governments a group of powerful Iraqi politicians and technocrats is pushing for a system of long term contracts with foreign oil companies which will be beyond the reach of Iraqi courts, public scrutiny or democratic control.

COSTING IRAQ BILLIONS

Economic projections published here for the first time show that the model of oil development that is being proposed will cost Iraq hundreds of billions of dollars in lost revenue, while providing foreign companies with enormous profits.

Our key findings are:

At an oil price of $40 per barrel, Iraq stands to lose between $74 billion and $194 billion over the lifetime of the proposed contracts (2), from only the first 12 oilfields to be developed. These estimates, based on conservative assumptions, represent between two and seven times the current Iraqi government budget.

Under the likely terms of the contracts, oil company rates of return from investing in Iraq would range from 42% to 162%, far in excess of usual industry minimum target of around 12% return on investment. A CONTRACTUAL RIP-OFF

The debate over oil “privatisation” in Iraq has often been misleading due to the technical nature of the term, which refers to legal ownership of oil reserves. This has allowed governments and companies to deny that “privatisation” is taking place. Meanwhile, important practical questions, of public versus private control over oil development and revenues, have not been addressed.

The development model being promoted in Iraq, and supported by key figures in the Oil Ministry, is based on contracts known as production sharing agreements (PSAs), which have existed in the oil industry since the late 1960s. Oil experts agree that their purpose is largely political: technically they keep legal ownership of oil reserves in state hands (3), while practically delivering oil companies the same results as the concession agreements they replaced.

Running to hundreds of pages of complex legal and financial language and generally subject to commercial confidentiality provisions, PSAs are effectively immune from public scrutiny and lock governments into economic terms that cannot be altered for decades.

In Iraq’s case, these contracts could be signed while the government is new and weak, the security situation dire, and the country still under military occupation. As such the terms are likely to be highly unfavourable, but could persist for up to 40 years.

Furthermore, PSAs generally exempt foreign oil companies from any new laws that might affect their profits. And the contracts often stipulate that disputes are heard not in the country’s own courts but in international investment tribunals, which make their decisions on commercial grounds and do not consider the national interest or other national laws. Iraq could be surrendering its democracy as soon as it achieves it.

POLICY DELIVERED FROM AMERICA TO IRAQ

Production sharing agreements have been heavily promoted by oil companies and by the US Administration.

The use of PSAs in Iraq was proposed by the Future of Iraq project, the US State Department’s planning mechanism, prior to the 2003 invasion. These proposals were subsequently developed by the Coalition Provisional Authority, by the Iraq Interim Government and by the current Transitional Government. The Iraqi Constitution also opens the door to foreign companies, albeit in legally vague terms.

Of course, what ultimately happens will depend on the outcome of the elections, on the broader political and security situation and on negotiations with oil companies. However, the pressure for Iraq to adopt PSAs is substantial. The current government is fast-tracking the process and is already negotiating contracts with oil companies in parallel with the constitutional process, elections and passage of a Petroleum Law.

The Constitution also suggests a decentralisation of authority over oil contracts, from the national level to Iraq’s regions. If implemented, the regions would have weaker bargaining power than a national government, leading to poorer terms for Iraq in any deal with oil companies.

A RADICAL DEPARTURE

In order to make their case, oil companies and their supporters argue that PSAs are standard practice in the oil industry and that Iraq has no other option to finance oil development. Neither of these assertions is true.

According to International Energy Agency figures, PSAs are only used in respect of about 12% of world oil reserves, in countries where oilfields are small (and often offshore), production costs are high, and exploration prospects are uncertain. None of these conditions applies to Iraq.

None of the top oil producers in the Middle East uses PSAs. Some governments that have signed them regret doing so. In Russia, where political upheaval was followed by rapid opening up to the private sector in the 1990s, PSAs have cost the state billions of dollars, making it unlikely that any more will be signed. The parallel with Iraq's current transition is obvious.

The advocates of PSAs also claim that obtaining investment from foreign companies through these types of contracts would save the government up to $2.5 billion a year, freeing up funds for other public spending. Although this is true, the investment by oil companies now would be massively offset by the loss of state revenues later.

Our calculations show that were the Iraqi government to use PSAs, its cost of capital would be between 75% and 119%. At this cost, the advantages referred to are simply not worth it.

Iraq has a range of less damaging and expensive options for generating investment in its oil sector. These include: financing oil development through government budgetary expenditure (as is currently the case), using future oil flows as collateral to borrow money, or using international oil companies through shorter-term, less restrictive and less lucrative contracts than PSAs (4).

IN WHOSE INTERESTS?

PSAs represent a radical redesign of Iraq's oil industry, wrenching it from public into private hands. The strategic drivers for this are the US/UK push for “energy security” in a constrained market and the multinational oil companies’ need to “book” new reserves to secure future growth.

Despite their disadvantages to the Iraqi economy and democracy, they are being introduced in Iraq without public debate.

It is up to the Iraqi people to decide the terms for the development of their oil resources. We hope that this report will help explain the likely consequences of decisions being made in secret on their behalf.

Notes

1. The Iraqi government would be left with control of only the 17 fields that are already in production, out of around 80 known fields.

2. The precise terms of proposed contracts are obviously be subject to negotiation: our projections are based on a range of terms used in the most comparable countries, including Libya, which is commonly viewed as having some of the most stringent in the world. Multinational oil companies are pushing for lucrative terms by international standards, based on Iraq’s high level of political and security risk. These risks place the Iraqi government in an extremely weak negotiating position. The projections are given in undiscounted real terms (2006 prices). The contract duration is assumed to be 30 years as 25-40 years is the common length. The (2006) net present value of the loss to Iraq amounts to between $16 billion and $43 billion at 12% discount rate.

3. The terminology of PSAs labels the private companies as “contractors”. This report illustrates that this label is misleading because PSAs give companies control over oil development and access to extensive profits.

4. These might include buyback contracts, risk service contracts or development and production contracts

Glossary

Back to top Bbl barrels

bn billion

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation

CPA Coalition Provisional Authority

DOE (US) Department of Energy

DPC development and production contract

FCO (UK) Foreign and Commonwealth Office

FDI foreign direct investment

FOB freight on board

GDP gross domestic product

ICSID International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

IMF International Monetary Fund

INOC Iraq National Oil Company

IOC international oil company

IPC Iraq Petroleum Company

ITIC International Tax and Investment Centre

IRR internal rate of return

kbpd thousand barrels per day

KRG Kurdistan Regional Government

mbd million barrels per day

MEES Middle East Economic Survey

MOU memorandum of understanding

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OPEC Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries

NPV net present value

PSA production sharing agreement

SERIS Sheffield Energy and Resources Information Service

UN United Nations

USAID United States Agency for International Development

1. The Ultimate Prize: Anglo-American interests in Gulf oil

Back to top The UK and US have long had their eyes on the massive energy resources of Iraq and the Gulf. In 1918 Sir Maurice Hankey, Britain’s First Secretary of the War Cabinet wrote:

“Oil in the next war will occupy the place of coal in the present war, or at least a parallel place to coal. The only big potential supply that we can get under British control is the Persian [now Iran] and Mesopotamian [now Iraq] supply… Control over these oil supplies becomes a first class British war aim.”(1)

After World War II both the US and UK identified the importance of Middle Eastern oil. British officials believed that the area was “a vital prize for any power interested in world influence or domination”(2), while their US counterparts saw the oil resources of Saudi Arabia as a “stupendous source of strategic power and one of the greatest material prizes in world history”(3).

TURNING BACK TO THE MIDDLE EAST

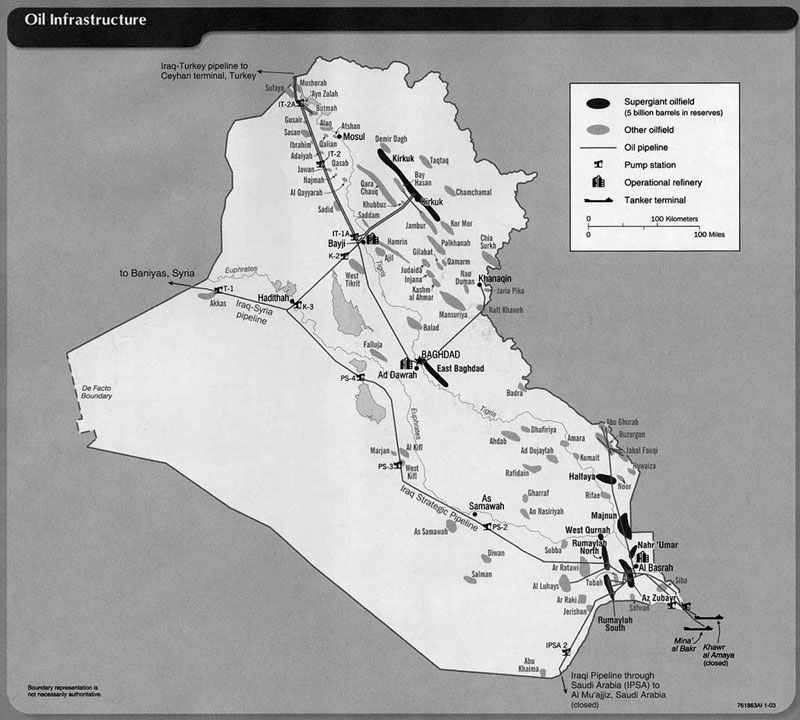

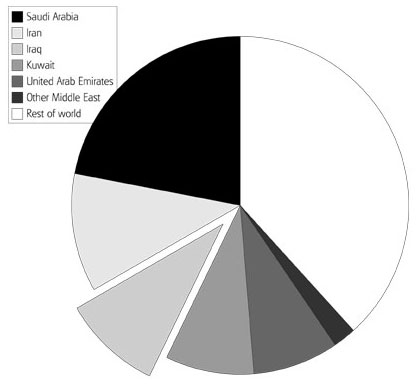

With over 60% of the world’s oil reserves,(4) their interest in the Gulf region is unsurprising. Iraq alone has the third largest oil reserves on the planet – accounting for 10% of the world total. Iraq is also reckoned to have the world’s largest unexplored potential, primarily in the Western Desert. On top of its 115 billion barrels of proven reserves, Iraq is estimated to have between 100 and 200 billion barrels of further possible (as yet undiscovered) reserves. Furthermore, not only are Iraqi and Gulf reserves huge, they are mostly onshore, in favourable reservoir structures, and extractable at extremely low cost.

Since the nationalisation of the major oil industries of the Middle East in the 1970s, Gulf reserves have been out of the direct control of the West and off the balance sheets of its companies. The oil companies have filled the gap by moving into the North Sea and Alaska in the 1970s and 1980s, and then in the 1990s by opening new ‘frontier’ areas such as the Caspian Sea and offshore West Africa.

However, the North Sea and Alaska are now in decline and while companies continue to actively pursue frontier oil development, the opportunities for growth there are limited and costs high. Thus, unable to escape from the arithmetic of where the giant reserves are, the US and UK are turning back their attention to the Middle East.

In a speech to the Institute of Petroleum in London in 1999, Dick Cheney, then CEO of oil services company Halliburton, commented:

“By 2010 we will need on the order of an additional fifty million barrels a day. So where is the oil going to come from? ... While many regions of the world offer great oil opportunities, the Middle East with two thirds of the world's oil and the lowest cost, is still where the prize ultimately lies.”(5)

To this analysis, he added a note of frustration: “Even though companies are anxious for greater access there, progress continues to be slow”.

A PRIMARY FOCUS OF US/UK ENERGY POLICY

Two years later, one of the Bush Administration’s first actions was to appoint Cheney, as US Vice President, to lead an Energy Task Force to consider where the USA’s long-term energy supplies would come from. His report noted:

“By any estimation, Middle East oil producers will remain central to world oil security. The Gulf will be a primary focus of U.S. international energy policy.”(6)

While US interest in Middle Eastern oil has been well-documented, similar considerations play in British strategic planning too. In January 2003, Foreign Secretary Jack Straw announced that one of the Foreign Office’s seven priorities was “to bolster the security of British and global energy supplies”.(7) The geography of such a policy had been spelled out in the 1998 Strategic Defence Review white paper:

“Outside Europe our interests are most likely to be affected by events in the Gulf and the Mediterranean. Instability in these areas also carries wider risks. We have particularly important national interests and close friendships in the Gulf. Oil supplies from the Gulf are crucial to the world economy.”(8)

Pointing to the government’s partnership on these issues with major oil companies, a further Foreign Office strategy paper later in 2003 identified a key objective as to:

“improve investment regimes and energy sector management in these regions [the Middle East, parts of Africa and the former Soviet Union], focusing on key links in the supply chain to the UK”(9) (emphasis added).

Importantly, these policies in America and Britain are coordinated. The US-UK Energy Dialogue - a bilateral initiative established during the April 2002 meeting of Prime Minister Blair and President Bush in Crawford, Texas(10), and designed to “enhance coordination and cooperation on energy issues” - demonstrates the close convergence of Anglo-American views and interests on Middle Eastern oil:

“Current forecasts for the oil sector put global demand by 2030 at about 120 million barrels per day (mbd), which is roughly 45 mbd higher than today. While recognizing that the increasing role of Russia and other non-OPEC producers, a large proportion of the world's additional demand will likely be met by the Middle East (mainly Middle East Gulf) producers. They hold over half of current proven reserves, exploration and production costs are the lowest in the world, and production in many mature fields in the OECD area is likely to fall. To meet future world energy demand, the current installed capacity in the Gulf (currently 23 mbd) may need to rise to as much as 52 mbd by 2030.”(11)

PUSHING FOREIGN INVESTMENT

However, as noted in the Dialogue, one obstacle to “free access” to oil that concerns the British and Americans is the lack of ‘installed extraction capacity’. To help deal with this problem President Bush and Prime Minister Blair tasked a joint Working Group with a list of planned activities. First on the list was to undertake “...a targeted study to examine the capital and investment needs of key Gulf countries...”.(12)

Within this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that in advising on the post-war reconstruction of Iraq, the British government has recommended that foreign investment in oilfields of most benefit to Iraq. In late summer 2004, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office issued a Code of Practice for the Iraqi oil industry, which argued that:

“It has been estimated that a minimum of US$ 4 billion would be needed to restore production to its 1990 levels of 3.5 million barrels per day (mbd), and perhaps US$ 25 billion to achieve 5 mbd. ... Given Iraq's needs, it is not realistic to cut government spending in other areas, and Iraq would need to engage with the International Oil Companies (IOCs) to provide appropriate levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to do this.”(13)

Photo: Greg Muttitt

The key US-UK "energy security" priority is secure control over an increasing supply of Gulf oil, preferably delivered by investment from their own companiesThe Foreign Office subsequently went on to advise the Ministry of Oil on “fiscal and regulatory” issues.(14) Although this was never published in a formal policy document, it continued at an informal level, with Foreign Office minister Kim Howells stating that “We discuss with the Iraqi Ministries their priorities on a regular basis.”(15) The FCO remains secretive about the content of this advice, refusing Freedom of Information applications. Tellingly, one of the exemptions used for their refusal was that the advice was “voluminous”.(16)

The US government too has maintained close contacts with Iraqi decision-makers.(17) Speaking on the handover from the Coalition Provisional Authority to the Iraqi Interim Government, one senior US official said:

“We're still here. We'll be paying a lot of attention and we'll have a lot of influence. We're going to have the world's largest diplomatic mission with a significant amount of political weight."(18)

A report commissioned by the US Agency for International Development was more specific about the form of contracts that should be used in Iraq, in order to achieve the West’s energy security goals:

“Using some form of [production sharing agreements] with a competitive rate of return has proved the most successful way to attract [international oil company] investment to expand oil productive capacity significantly and quickly.”(19)

As the above policies illustrate, the key US-UK ‘energy security’ priority is secure control over an increasing supply of Gulf oil, preferably delivered by investment from their own oil companies. It is clear that Iraq's newly accessible oil is expected to play an important role in meeting these priorities. But as we shall see, implementing these arrangements could have severe impacts on Iraq’s future development.

2. Re-thinking privatisation: Production sharing agreements

Back to top THE NATURE OF "PRIVATISATION"

Given the West’s fundamental strategic interest in the oil reserves of Iraq and the Gulf as outlined in the previous section, some observers were surprised when the oil sector was excluded from the sweeping privatisations of Iraq’s economy by US Administrator Paul Bremer in 2003 and 2004. Decisions on the future structure of the oil industry were deferred, to be addressed by an elected Iraqi government.

The Coalition Provisional Authority only awarded short-term repair and restoration contracts – for service companies such as Halliburton and Parsons to restore the country’s existing oil infrastructure, which had been damaged by war and sanctions – rather than long-term extraction concessions. In February 2005, Interim Oil Minister Thamer al-Ghadban stated that "As for the extraction sector, that is, dealing with the oil and gas reserves, which are 'assets', privatisation is completely out of the question at the moment."(20)

But if the non-privatisation of oil was a surprise, this was largely based on a misconception of what “privatisation” means in the Iraqi context. In the minds of some neo-conservatives, writing on Iraqi oil before the war, privatisation meant the transfer of legal ownership of Iraq's oil reserves into private hands. However, in all countries of the world except the USA (a), reserves (prior to their extraction) are legally the property of the state. This is the case in Iraq, and remains so under the new Constitution. There has never been a realistic prospect of US-style privatisation of Iraq’s oil reserves. But this does not mean that private companies would not develop Iraq’s oil.

In some ways, the debate on “privatisation” has obscured the important practical issues of who gets the revenue from the oil, and who controls the way in which oil is developed. On this matter, Iraq has a relevant history.

The development of Iraq’s oil industry began in the aftermath of the First World War, while the country was occupied by Britain under a League of Nations Mandate. In 1925, Iraq’s British-installed monarch, King Faisal, signed a concession contract with the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC)(21), a consortium of British, French and (later) American oil companies. The contract followed a model widely applied in the British colonies. It was for a period of 75 years, during which terms were frozen. Combined with two further concessions granted in the 1930s, the IPC obtained rights to all of the oil in the entire country. Even the Iraqi call for a 20% stake in the concession was denied, despite having been specified in earlier agreements.

As Iraqi frustration at the unfair terms of the deal grew, in the 1950s and 1960s the contract came under pressure. Underpinning this were the issues of whether the split of revenues between company and state was a fair one, and the degree of control the foreign companies had over the development: they restricted production to boost their producing areas elsewhere in the world, and used their monopoly on information to fix prices, depriving Iraq of income. These same arguments were echoed in all of the major oil-producing countries at the time, most of which had similar deals with multinational companies. The ultimate conclusion to these disputes was the nationalisation of many oil industries – in Iraq’s case in two stages in 1961 and 1972.(b)

INTRODUCING PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENTS

While these disputes were raging in the Middle East, a different model was emerging in Indonesia. There, a new form of contract was introduced in the late 1960s: the production sharing agreement (PSA).

An ingenious arrangement, PSAs shift the ownership of oil from companies to state, and invert the flow of payments between state and company. Whereas in a concession system, foreign companies have rights to the oil in the ground, and compensate host states for taking their resources (via royalties and taxes), a PSA leaves the oil legally in the hands of the state, while the foreign companies are compensated for their investment in oil production infrastructure and for the risks they have taken in doing so.

Although many in the oil industry were initially suspicious of Indonesia’s move, they soon realised that by setting the terms the right way, a PSA could deliver the same practical outcomes as a concession, with the advantage of relieving nationalist pressures within the country. In one of the standard textbooks on petroleum fiscal systems, industry consultant Daniel Johnston comments:

“At first [PSAs] and concessionary systems appear to be quite different. They have major symbolic and philosophical differences, but these serve more of a political function than anything else. The terminology is certainly distinct, but these systems are really not that different from a financial point of view.”(22)

So, the financial and economic implications of PSAs may be the same as concessions, but they have clear political advantages – especially when contrasted with the 1970s nationalisations in the Middle East. Professor Thomas Wälde, an expert in oil law and policy at the University of Dundee, describes them as:

“A convenient marriage between the politically useful symbolism of the production-sharing contract (appearance of a service contract to the state company acting as master) and the material equivalence of this contract model with concession/licence regimes in all significant aspects…The government can be seen to be running the show - and the company can run it behind the camouflage of legal title symbolising the assertion of national sovereignty.”(23)

As we will see, these advantages now appear to make PSAs the Western method of choice for future development of the Iraqi oil industry.

OPTIONS FOR OIL POLICY

There are essentially three models a country may choose from for the structure of its oil industry, plus a number of variations on these themes.

1. The system currently in place in Iraq, which has been the case since the early 1970s, is a NATIONALISED INDUSTRY. In this model, the state makes all of the decisions, and takes all of the revenue. The extent of involvement of foreign private companies is that they might be hired to carry out certain services under contract (a technical service contract) – a well-defined piece of work, for a limited period of time, and for which they receive a fixed fee. This is the model used throughout most of the Gulf region.

One variant on the technical service contract is the risk service contract. In this system, a private company provides capital to invest in a project, but is paid a fixed rate of return, agreed in the contracts (thus preventing excessive profits). A similar mechanism is the buyback contract, which has been used on some fields in Iran, in which companies also have a right to buy the oil or gas.

2. In the CONCESSION model, sometimes known as the tax and royalty system, the government grants a private company (or more often, a consortium of private companies) a license to extract oil, which becomes the company’s property (to sell, transport or refine) once extracted. The company pays the government taxes and royalties for the oil.

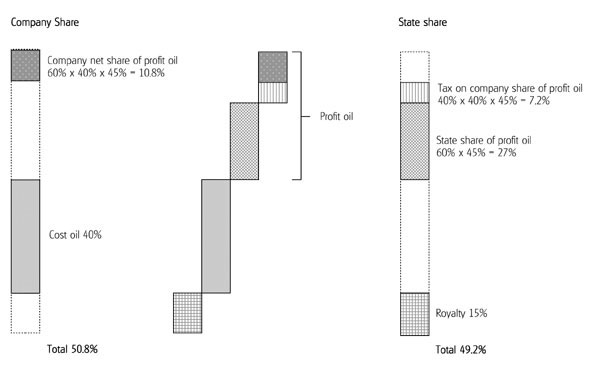

3. The PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (PSA) is a more complex system. In theory, the state has ultimate control over the oil, while a private company or consortium of companies extracts it under contract. In practice, however, the actions of the state are severely constrained by stipulations in the contract. In a PSA, the private company provides the capital investment, first in exploration, then drilling and the construction of infrastructure. The first proportion of oil extracted is then allocated to the company, which uses oil sales to recoup its costs and capital investment – the oil used for this purpose is termed ‘cost oil’. There is usually a limit on what proportion of oil production in any year can count as cost oil. Once costs have been recovered, the remaining ‘profit oil’ is divided between state and company in agreed proportions. The company is usually taxed on its profit oil. There may also be a royalty payable on all oil produced.

Sometimes the state also participates as a commercial partner in the contract, operating in joint venture with foreign oil companies as part of the consortium – with either a concession or a PSA model. In this case, the state generally provides its percentage share of development investment and directly receives the same percentage share of profits.

3. Pumping profits: Big Oil and the push for PSAs

Back to top As with many issues of foreign policy, the interests of the world’s largest oil corporations mesh closely with those of their national governments – as we saw in section 1. While the governments seek secure and adequate supplies of oil to feed their economies, the corporations need control over reserves to ensure their future profitability, to deliver returns to their shareholders. For governments, “secure” oil supplies often means that they are in fact part-controlled by major oil corporations based in their own countries.

For their part, major multinational oil companies have made no secret of their desire to gain access to Iraq’s reserves. Shortly before the invasion Archie Dunham, chairman of US oil major ConocoPhillips, explained that “We know where the best [Iraqi] reserves are [and] we covet the opportunity to get those some day.”(24) Shell has stated that it aims to “establish a material and enduring presence in the country.”(25)

Since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, foreign oil companies have worked hard to build relationships with Iraq’s Oil Ministry. They have appointed lobbyists to develop relationships with influential officials, provided training (often for free) for Iraqi officials and technicians, sponsored Oil Ministry participation in international conferences, and entered contracts (again, often for free) to analyse oilfield geological data.

In 2004, Shell recruited an Iraqi external affairs officer to help the company gain access to Iraqi government decision-makers, specifying in their advertisement:

“A person of Iraqi extraction with strong family connections and an insight into the network of families of significance within Iraq”.(26)

Through these means, the companies aim to be well-positioned when it comes to the signing of contracts.

WHAT OIL COMPANIES WANT

It is helpful at this point to look at the companies’ agenda for Iraq. Oil corporations are looking for three things when they invest in a country, all of which are delivered by production sharing agreements:

Photo: Greg Muttitt

Oil companies covet Iraq's oil wealth, and are pushing for access to it through production sharing agreements1. A right to oil reserves. Companies want a deal that guarantees their right to extract the reserves for many years, thus ensuring their future growth and profits. Furthermore, they want a contract that allows them to ‘book’ these reserves – including them in their accounts – which increases their company value. Production sharing agreements, like concession contracts, permit companies to book reserves in their accounts. The importance of this should not be underestimated for the oil majors. In 2004, when British/Dutch oil company Shell was found to have overstated the size of its ‘booked’ reserves by over 20%, it lost the faith of the financial markets: this impacted heavily on its share price and credit rating. Shell is now desperate to acquire new reserves – which is a key reason why Shell has made more effort than most to make friends in Iraq.

2. An opportunity to make large profits. Generally, oil companies make their profits from investing and risking their capital. In some cases, they lose their capital, for example when they drill a ‘dry well’. But in some cases they will find large and hugely profitable fields. Oil companies are therefore very different from service companies like Halliburton, which make money from fixed fees on predictable contracts. Oil companies aim for deals which may be more speculative, but which give them a chance of making super-profits. Production sharing agreements are designed to allow companies to achieve very large profits if successful.

3. Predictability of tax and regulation. While companies can accept exploration risk (that they won’t find oil) or price risk (that the oil price falls), both being beyond their control, they try to manage ‘political risk’ (that tax or regulatory demands will increase) by locking in governments. They thus seek to bind governments into long-term contracts that fix the terms of their investment. Production sharing agreements generally last for 25 to 40 years with terms protected from potential change by incoming governments.

Shell’s head of Exploration & Production, speaking at a conference in 2003, made the case for PSAs:

“...international oil companies can make an ongoing contribution to the region [the Persian/Arabian Gulf]... However, in order to secure that investment, we will need some assurance of future income and, in particular, a supportive contractual framework. There are a number of models which can achieve these ends. One option is the greater use of production sharing agreements, which have proved very effective in achieving an appropriate balance of incentives between Governments and oil companies. And they ensure a fair distribution of the value of a resource while providing the long term assurance which is necessary to secure the capital investment needed for energy projects.”(27)

THE VOICE OF BIG OIL

The most detailed expression of what the oil companies are seeking in Iraq has been made by the International Tax & Investment Centre (ITIC), a corporate lobby group pushing for pro-business investment and tax reform.

Almost all of ITIC's 110 listed sponsors are large corporations, with roughly a quarter of these in the oil sector. ITIC’s Board of Directors contains representatives from Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil and ChevronTexaco. Since its launch in 1993, ITIC has primarily focused on the former Soviet Union, but more recently, it has expanded its work to include Iraq. Its 2004 strategy review concluded that this project “should be continued and considered as a “beachhead” for possible further expansion in the Middle East.”(28)

In autumn 2004 ITIC issued a major report entitled Petroleum and Iraq's Future: Fiscal Options and Challenges, which includes the following key recommendations:

“The most appropriate legal and fiscal form for the facilitation of [Foreign Direct Investment] longer-term development of Iraq's petroleum industry will be a production sharing agreement (PSA).”(29) Foreign Direct Investment, by ITIC members and other multinational oil companies, would “effectively “kick start” the [Iraqi] economy and avoid the government diverting spending to oil development that is sorely needed for other programmes.”(30) PSAs are lauded as providing the “simplest and most attractive regulatory ... framework” which the ITIC claims are now the “norm in most countries outside the OECD.”(31) Having reviewed the various options, with due consideration to “international experience and regional preferences”, the ITIC concludes that the alternative models are far inferior to PSAs.

INAPPROPRIATE FOR IRAQ

PSAs are indeed quite common in countries with small oil reserves and/or high extraction costs (especially from offshore fields) and/or high exploration or technical risks. However, none of these conditions apply to Iraq; in fact, Iraq is quite the opposite. PSAs are not found in any other country comparable to Iraq.

It is difficult to overstate how radical a departure PSAs would be from normal practice, both in Iraq and in other comparable countries of the region. Iraq’s oil industry has been in public hands since 1972; prior to that the rights to develop oil in 99.5% of the country had also been publicly held since 1961.(c)

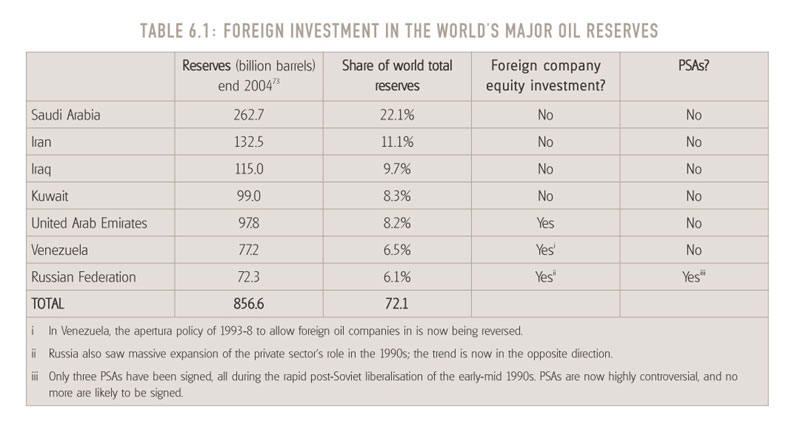

In Iraq’s neighbours Kuwait, Iran and Saudi Arabia, foreign control over oil development is ruled out by constitution or by national law. These countries together with Iraq are the world’s top four countries in terms of oil reserves, with 51% of the world total between them.(32)

Together with the United Arab Emirates, Venezuela and Russia, seven countries hold 72% of the world’s oil reserves. These latter three all have some foreign involvement through concession agreements, although both Venezuela and Russia are currently drawing back from it, following unsuccessful expansions in foreign investment in the 1990s. Of these seven countries with major oil reserves, only Russia has any production sharing agreements. Russia signed three PSAs in the mid 1990s; however, PSAs have been the subject of extreme controversy ever since, due to the poor deal the state has obtained from them, and it now looks unlikely that any more will be signed.

Countries with reserves the size of Iraq’s do not use PSAs because they do not need to and are able to run their oil industries on far more beneficial terms.

4. From Washington to Baghdad: Planning Iraq's oil future

Back to top PRE-INVASION PLANNING

Current Iraqi oil policy - first designed in

Washington, DC - would give at least 4% of Iraq's reserves to foreign companiesPrior to the 2003 invasion, the principal vehicle for planning the new post-war Iraq was the US State Department’s Future of Iraq project. This initiative, commencing as early as April 2002, involved meetings in Washington and London of 17 working groups, each comprised of 10-20 Iraqi exiles and international experts selected by the State Department(33).

The “Oil and Energy” working group met four times between December 2002 and April 2003. Although the full membership of the group has never been revealed, it is known that Ibrahim Bahr al-Uloum, the current Iraqi Oil Minister, was a member.(34) The 15-strong oil working group concluded that Iraq “should be opened to international oil companies as quickly as possible after the war” and that “the country should establish a conducive business environment to attract investment of oil and gas resources.”(35)

The subgroup went on to recommend production sharing agreements (PSAs) as their favoured model for attracting foreign investment. Comments by the handpicked participants revealed that “many in the group favoured production-sharing agreements with oil companies.” Another representative commented, “Everybody keeps coming back to PSAs.”(36)

The reasons for this choice were explained in the formal policy recommendations of the working group, published in April 2003:

“Key attractions of production sharing agreements to private oil companies are that although the reserves are owned by the state, accounting procedures permit the companies to book the reserves in their accounts, but, other things being equal, the most important feature from the perspective of private oil companies is that the government take is defined in the terms of the [PSA] and the oil companies are therefore protected under a PSA from future adverse legislation.”(37)

The group also made it clear that in order to maximize investments, the specific terms of the PSAs should be favourable to foreign investors:

“PSAs can induce many billions of dollars of foreign direct investment into Iraq, but only with the right terms, conditions, regulatory framework, laws, oil industry structure and perceived attitude to foreign participation.”(38)

Recognising the importance of this announcement, The Financial Times noted:

“Production-sharing deals allow oil companies a favourable profit margin and, unlike royalty schemes, insulate them from losses incurred when the oil price drops. For years, big oil companies have been fighting for such agreements without success in countries such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.”(39)

The article concluded that: “The move could spell a windfall for big oil companies such as ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch/Shell, BP and TotalFinaElf...”

SHAPING THE NEW IRAQ

The US and UK have worked hard to ensure that the future path for oil development chosen by the first elected Iraqi government will closely match their interests. So far it appears they have been highly successful: production sharing agreements, which were first proposed by the U.S. State Department group, have emerged as the model of oil development favoured by all the post-invasion phases of Iraqi government.

Phase 1: Coalition Provisional Authority and Iraqi Governing Council

During the first fourteen months following the invasion, occupation forces had direct control of Iraq through the Coalition Provisional Authority. Stopping short of privatising oil itself, the CPA began setting up the framework for a longer-term oil policy.

The CPA appointed former senior executives from oil companies to begin this process. The first advisers were appointed in January 2003, before the invasion even started, and were stationed in Kuwait ready to move in. First, there were Phillip Carroll, formerly of Shell, and Gary Vogler, of ExxonMobil, backed up by three employees of the US Department of Energy and one of the Australian government. Carroll described his role as not only to address short-term fuel needs and the initial repair of production facilities, but also to:

“Begin planning for the restructuring of the Ministry of Oil to improve its efficiency and effectiveness; [and]

Begin thinking through Iraq’s strategy options for significantly increasing its production capacity.”(40) In October 2003, Carroll and Vogler were replaced by Bob McKee of ConocoPhillips, and Terry Adams of BP, and finally in March 2004, by Mike Stinson of ConocoPhillips and Bob Morgan of BP (d). The £147,700 cost of the two British advisers, Adams and Morgan, was met by the UK government.(41) Following the handover to the Iraq Interim Government in June 2004, Stinson became an adviser to the US Embassy in Baghdad.

On 13 July 2003, in the first move towards Iraqi self-government, the CPA Administrator Paul Bremer appointed the quasi-autonomous, but virtually powerless, Iraqi Governing Council. On the same day Bremer appointed Ibrahim Bahr al-Uloum, who had been a member of the U.S. State Department oil working group, as Minister for Oil.

Within months of his appointment Bahr al-Uloum announced that he was preparing plans for the privatisation of Iraq's oil sector, but that no decision would be taken until after elections scheduled for 2005.(42)

Speaking to the Financial Times, Bahr al-Uloum, a US-trained petroleum engineer, said: "The Iraqi oil sector needs privatisation, but it's a cultural issue,” noting the difficulty of persuading the Iraqi people of such a policy. He then proceeded to announce that he personally supported:

Production sharing agreements for upstream (i.e. extraction of crude oil) development;

giving priority to US oil companies, “and European companies, probably.”(43) Phase 2: Iraq Interim Government

In June 2004, the CPA formally handed over Iraqi sovereignty to an interim government, headed by Prime Minister Iyad Allawi.

The position of Minister of Oil was handed to Thamir al-Ghadban, a UK-trained petroleum engineer and former senior adviser to Bahr al-Uloum. In an interview in Shell’s in-house magazine, al-Ghadban announced that 2005 would be the “year of dialogue” with multinational oil companies.(44)

About three months after taking power, Allawi issued a set of guidelines to the Supreme Council for Oil Policy, from which the Council was to develop a full petroleum policy. Pre-empting both the Iraqi elections and the drafting of a new constitution, Allawi’s guidelines specified that while Iraq’s currently producing fields should be developed by the Iraq National Oil Company (INOC), all other fields should be developed by private companies, through the contractual mechanism of production sharing agreements (PSAs).(45)

Iraq has about 80 known oilfields, only 17 of which are currently in production. Thus the Allawi guidelines would grant the other 63 to private companies.

Allawi also added that:

New fields would be developed exclusively by private companies, with the policy ruling out any participation of INOC;(46)

The national oil company INOC, which manages existing oil fields, should be part-privatised;(47)

The Iraqi authorities should not spend time negotiating the best possible deals with the oil companies; instead they should proceed quickly, agreeing whatever terms the companies will accept, with a possibility of renegotiation (e) later.(48) Phase 3: Transitional Government and writing the Constitution

The interim government was replaced in early 2005 by the election of Iraq's new National Assembly, which led to the formation of the new government with Ibrahim al-Ja’afari as Prime Minister. In a move which no doubt assisted policy continuity from the period of US control, Ibrahim Bahr al-Uloum was reappointed to the position of Minister for Oil.

Meanwhile, Ahmad Chalabi, the Pentagon’s former favourite to run Iraq, was appointed chair of the Energy Council, which replaced the Supreme Council for Oil Policy as the key overseer of energy and oil policy. Back in 2002 Chalabi had famously promised that “US companies will have a big shot at Iraqi oil.”(49)

By June 2005, government sources reported that a Petroleum Law (f) had been drafted, ready to be enacted after the December elections. According to the sources – although some details are still being debated – the draft of the Law specifies that while Iraq’s currently producing fields should be developed by INOC, new fields should be developed by private companies.

In October 2005, a new Constitution was accepted in a referendum of the Iraqi population. Like much of the Constitution, the oil policy section is open to some interpretation. Apparently referring to fields not currently in production, it states:

“The federal government and the governments of the producing regions and provinces together will draw up the necessary strategic policies to develop oil and gas wealth to bring the greatest benefit for the Iraqi people, relying on the most modern techniques of market principles and encouraging investment.”(50)

There are two issues here. The reference to “market principles and encouraging investment” indicates a clear direction of travel, in terms of opening to private companies. Meanwhile the first part of this clause, somewhat vaguely, tries to deal with the issue of jurisdiction. However, while this states that the federal and regional governments will work together, a subsequent clause states that:

“All that is not written in the exclusive powers of the federal authorities is in the authority of the regions. In other powers shared between the federal government and the regions, the priority will be given to the region's law in case of dispute.”(51)

Signing of contracts for extraction of oil and other natural resources is not listed(52) as one of the exclusive powers of the federal authorities – the implication is thus that on new fields, it is the authority of the regional governments.

This situation is quite unclear, and is further muddied by a last-minute deal, arranged just before the constitutional referendum, that the Constitution could be amended in the first half of 2006, and by comments by Zalmay Khalilzad, US Ambassador to Iraq, that “after that, as Iraq evolves, so, too, will this charter evolve”.(53)

In so far as the decision rests with Baghdad, the Oil Ministry is keen to sign contracts as quickly as possible. According to officials in the Ministry, their aim is to begin signing long-term contracts with foreign oil companies during the first nine months of 2006.(54) In order to achieve this goal, officials wanted to start negotiations with oil companies during the second half of 2005, before a legitimate Iraqi government is elected and in parallel with the writing of a Petroleum Law.(55) This time frame means that contracts will be negotiated without public participation or debate, or proper legal framework.

Meanwhile, the Kurdish authorities are even more impatient to sign deals. In June 2004, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) signed an exploration and development deal with Norwegian company DNO. In a clear sign of the tensions between Baghdad and the regions, the Oil Ministry reacted by warning companies that if they signed deals with regional governments, they would be excluded from contracts at a national level.

Then in October 2005, the KRG signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with K Petroleum Company, which is jointly owned by the Canada-based Heritage Oil and the Kurdish company Eagle, to carry out oilfield studies adjacent to the Taq Taq field in Kurdistan. Announcing the deal, Heritage stated that

“Negotiations to formalize the MOU into a Production Sharing Agreement(PSA) are scheduled to commence while the work program is being carried out.KPC is confident these studies will translate into a PSA, although there is no guarantee that a license will be awarded to the Company.”(56)

For the southern oilfields, the outlook is less clear. In any case, regional governments of both Kurdistan and southern Iraq would have far weaker bargaining power in negotiating with foreign oil companies than the Iraqi Oil Ministry (or Iraq National Oil Company), as they lack both the institutional experience and the consolidated weight of handling the entire country’s resources. The likely result would be more negative terms than could be achieved at a national level.

As noted above, only 17 of Iraq’s 80 known fields are currently in production.(57) As these 17 fields represent only 40 billion of Iraq's 115 billion barrels of known oil reserves, the policy to allocate undeveloped fields to foreign companies would give those companies control of 64% of known reserves.(58) If a further 100 billion barrels are found, as is widely predicted, the foreign companies could control as much as 81% of Iraq's oil; if 200 billion are found, as the Oil Ministry predicts, the foreign company share would be 87%.

Given that oil accounts for over 95% of Iraq’s government revenues(59), the impact of this policy on Iraq’s economy would be enormous.

5. Contractual rip-off: The cost of PSAs to Iraq

Back to top While the advantages of production sharing agreements for multinational oil companies are clear, there is a severe shortage of independent analysis of whether PSAs are in the short, medium and long-term interests of the Iraqi people. Unfortunately the Iraqi people have not been informed of the pro-PSA oil development plans, let alone their implications, which have transformed so seamlessly from US State Department recommendations into Iraqi government policy. This report hopes to go some way towards redressing this balance.

Our analysis shows that production sharing agreements have two major disadvantages for the Iraqi people:

1. The loss of hundreds of billions of dollars in potential revenue;

2. The loss of democratic control of Iraq's oil industry to international companies;

PSAs may also undermine an important opportunity to establish effective public oversight and end the current corruption and financial mismanagement in the Iraqi oil sector (see Section 6).

PSAs generally last (with fixed terms) for between 25 and 40 years: thus once signed the Iraqi people would have to live with the consequences for decades.

LOSING REVENUE: HOW MUCH WOULD PSAS COST THE IRAQI PEOPLE?

In order to understand why foreign oil companies are so keen to invest in Iraq, one needs to look at the economic outcomes that would result from applying PSA contracts to the Iraqi oil sector.

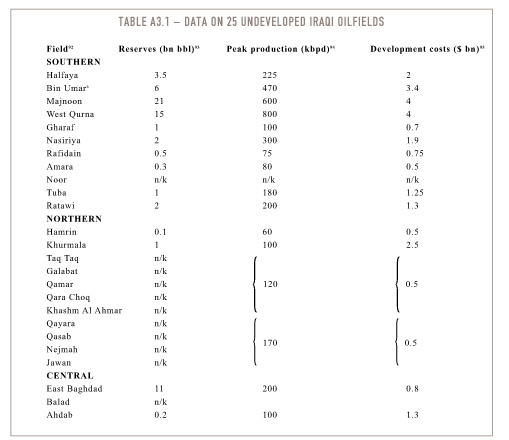

We have produced economic models of 12 of Iraq’s oilfields that have been listed as priorities for investment under production sharing agreements. We do not know yet what terms Iraqi contracts might contain (that will not be known until they are signed – and possibly not at all, if they are not disclosed to the public). Therefore we have taken contractual terms used in other comparable countries, and applied them to the physical characteristics of Iraq’s oilfields (based on data from the Iraqi Oil Ministry, the US Government and respected industry analysts such as Deutsche Bank – see Appendix 3). This process allows us to project the cashflows to the Iraqi state and to foreign oil companies, under a range of assumptions (such as oil price).

Specifically, we look at terms used in Oman and Libya (both having comparable physical conditions to Iraq) and Russia (the only country with any PSAs which has reserves at all comparable in scale to Iraq’s). The terms recently applied in Libya are widely viewed to be among the most stringent in the world. We have then compared the results with expected revenues of a nationalised system, administered by state-owned oil companies.(g)

Using an average oil price of $40 per barrel, our projections reveal that the use of PSAs would cost Iraq between $74 billion and $194 billion in lost revenue, compared to keeping oil development in public hands.

This massive loss is the equivalent of $2,800 to $7,400 per Iraqi adult over the thirty-year lifetime of a PSA contract. By way of comparison Iraqi GDP currently stands at only $2,100 per person, despite the very high oil price.(60)

It should be noted that these figures relate to only 12 of Iraq’s more than 60 undeveloped fields. Iraq has identified 23 priority fields on which to potentially sign contracts in 2006.(h) Thus when the other 11 fields are added, along with a further 35 or more later, and especially other fields yet to be discovered (recall that Iraq’s undiscovered reserves may be as large or even double the known reserves), the full cost of the PSA policy could be considerably greater.

We have been deliberately conservative with our assumptions. Our assumptions and methodology are outlined in Appendix 4.

Both the corporate lobby group ITIC (see section 3) and the British Foreign Office have argued that foreign investment can free up Iraqi government budgets for other priority areas of spending, to the tune of around $2.5 billion a year.(61) Although technically true, this is deeply misleading – as the investment now would be offset by the loss of revenues later.

Amazingly, in ITIC’s report advocating the use of PSAs, the economic impact is only examined up to 2010(62) – ignoring the fact that any foreign investment must be repaid.(j) It is as if one took out a bank loan but only considered the economic impact prior to paying it back!

The use of PSAs could deprive Iraq of $190 billion of revenueIn contrast, in this report, we look at the impact of PSAs over the whole length of the contract. Economists and indeed oil companies compare investments using the process of ‘discounting’, and the concept of ‘net present value’ (NPV). NPV is a measure of what the later income or expenditure would be worth if they were received or incurred now (See Appendix 2).

When looked at in these terms, far from ‘saving’ the government $8.5 billion of investment (the whole investment over several years, in 2006 NPV), these contracts will cost Iraq a (2006) NPV of $16 - $43 billion, at a 12% discount rate.(k)

Our assumed oil price for these calculations is $40 per barrel. The oil price is currently fluctuating around $60 per barrel, and there is an argument that structural factors, such as increasing demand in China and India, mean that oil prices are likely to stay at this level – which would make our $40 assumption conservative.

However, the oil price is notoriously difficult to predict. We therefore also look at the models at a higher price of $50 and a lower price of $30 per barrel. Here the models show that Iraq would lose $55 to $143 billion at $30 per barrel, while if the oil price averaged a higher $50 per barrel, Iraq would lose far greater revenues of $94 - $250 billion, compared to the nationalised model.

MASSIVE PROFITS: HOW MUCH DO THE OIL COMPANIES STAND TO GAIN?

Our economic model has also been used to calculate the key measure of oil project profitability - the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) (see Appendix 2) - which the oil companies are expected to make. This provides another measure of whether PSAs represent a fair deal for Iraq.

Profitability varies according to the size of the oil field, so we have based our projections on three different fields which (in Iraqi terms) are typical small, medium and large oil fields.

Our figures show that under any of the three sets of PSA terms, oil company profits from investing in Iraq would be quite staggering, with annual rates of return ranging from 42% to 62% for a small field, or 98% to 162% for a large field. This shows that under PSAs, Iraq's loss in terms of government revenue will be the oil companies’ gain.

By way of comparison, oil companies generally consider any project that generates an IRR of more than a 12% to be a profitable venture. For Iraqi oil fields, even under the most stringent PSA terms, it is clear that the oil companies can expect to achieve stellar returns.

Even at prices of $30/barrel, profits are excessive on all fields, with any terms, ranging from 33% on a small field with stringent terms to 140% on a large field with lucrative terms. At $50/barrel, the profits are even greater, ranging from 48% to 178%.

LOSING CONTROL: THE DEMOCRATIC COST OF PSAS

Iraq's democracy is new and weak. Having suffered decades of oppression by Saddam Hussein, Iraq's institutions and civil society need time to develop and mature. In this situation many Iraqis may feel that they do not wish to immediately lock their country into any single model of oil development over the long term. Unfortunately this is exactly what Iraqi politicians, under US and UK pressure, appear to want to do.

As we saw in section 2, in theory PSAs would allow the Iraqi state to retain ownership and control over their oil resources. However, in practice they will impose severe restrictions on current and future Iraqi governments for the full lifetime (25-40 years) of the contract.

PSAs have four key features that will in practice limit and remove democratic control from the Iraqi people:

They fix terms for 25-40 years, preventing future elected governments from changing the contract. Once a deal is signed, its terms are fixed. The contractual terms for the following decades will be based on the bargaining position and political balance that exists at the time of signing – a time when Iraq is still under military occupation and its governmental institutions are weak. In Iraq’s case, this could mean that arguments about political and security risks in 2006 could land its people with a poor deal that long outlasts those risks and is completely unsuited to a potentially more stable and independent Iraq of the future. Secondly, they deprive governments of control over the development of their oil industry. PSA contracts generally rule out government influence over oil production rates.(63) As a result, Iraq would not be able to control the depletion rate of its oil resources – as an oil-dependent country, the depletion rate is absolutely key to Iraq’s development strategy, but would be largely out of the government’s control. Unable to hold back foreign companies’ production rates, Iraq would also be likely to have difficulty complying with OPEC quotas which would harm Iraq’s position within OPEC, and potentially the effectiveness of OPEC itself. The only way to avoid either of these two problems would be for Iraq to cut back production on the fields controlled by state-owned oil companies, reducing revenues to the state. Thirdly, they generally over-ride any future legislation that compromises company profitability, effectively limiting the government's ability to regulate. One of the most worrying aspects of PSAs is that they often contain so-called ‘stabilisation clauses’, which would immunise the 60-80% of the oil sector covered by PSAs from all future laws, regulations and government policies. Put simply, under PSAs future Iraqi governments would be prevented from changing tax rates or introducing stricter laws or regulations relating to labour standards, workplace safety, community relations, environment or other issues. One common way of doing this is for contracts to include clauses that allocate the 'risks' for such tax or legislative change to the state.(64) In other words, if the Iraqis decided to change their legislation, they would have to pick up the bill themselves. The foreign oil company's profits are effectively guaranteed. Fourthly, PSAs commonly specify that any disputes between the government and foreign companies are resolved not in national courts, but in international arbitration tribunals which will not consider the Iraqi public interest. Within these tribunals, such as those administered by the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes in Washington DC, or by the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris, disputes are generally heard by corporate lawyers and trade negotiators who will only consider the narrow commercial issues and who will disregard the wider body of Iraqi law. As the researcher Susan Leubuscher comments, “That system assigns the State the role of just another commercial partner, ensures that non-commercial issues will not be aired, and excludes representation and redress for populations affected by the wide-ranging powers granted [multinationals] under international contracts.”(65) They may also – especially if connected to bilateral investment treaties – make a foreign company’s home state a party to any dispute, thus enabling that country to weigh in on the company’s behalf.

Photo: Greg Muttitt

Under PSAs, Iraq would hand sovereignty over oil resources, to foreign companies and international investment courtsThis loss of democratic control is illustrated by the case of BP’s Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline, which is being built from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean. This project is governed by a Host Government Agreement, some of whose legal provisions are comparable to those in PSAs.

In November 2002, the Georgian Environment Minister said she could not approve the pipeline routing through an important National Park, as to do so would violate Georgia’s environmental laws. Both BP and the US government put pressure on the Minister, through then President Shevardnadze. The Minister was forced first to concede the routing with environmental conditions, and then to water down her conditions. Part of the reason for her weak bargaining position was that two years earlier Georgia had signed the Host Government Agreement for the project, which set a deadline for environmental approval within 30 days of the application and stipulated that the contract had a higher status than other Georgian laws. The environment laws the Minister referred to were irrelevant. Ultimately, on the day of the deadline, the President called the Minister into his office, and kept her there until she signed, in the early hours of the morning.(6)

Shortly after Shevardnadze was overthrown in a ‘rose revolution’ in November 2003, new President Mikhail Sakashvili commented, “We got a horrible contract from BP, horrible”(67) – but he could not change it.

MULTINATIONAL COMPANIES FAVOUR COMPLEXITY

Another feature of production sharing agreements is that they are the most contractually complex form of oil contract. PSAs generally consist of several hundred pages of technical legal and financial language (often treated as commercially confidential). It is their complexity, not their simplicity, which is advantageous to oil companies.

The simplest form of oil fiscal system is the royalty (defined as a percentage of the total value of the oil), which can be seen as a company paying the state for its oil – effectively ‘buying’ it. This is used in most concession agreements, and sometimes in PSAs. In comparison with production sharing formulae, it is very clear what the state should receive from royalties – a fixed percentage of the value of oil. As long as the number of barrels extracted is known, and the oil price, it is easy to work out what royalty is due from the oil companies.

However oil companies dislike royalties and prefer systems based on an assessment of profits, such as PSAs. The reason is that they want what they call ‘upside’ (i.e. opportunities for greater profits) – ways they can reduce their payments, rather than being subject to a fixed level of payment for oil extracted.

Under profit-based systems, revenue is based on the profit remaining when the oil companies’ production costs have been deducted from the total revenue. As such, they depend on complex rules for which costs can be deducted, how capital costs are to be treated, and so on. The more complicated the system, the more opportunities there are for a company to maximise their share of the revenue by sophisticated use of accountancy techniques. Not only do multinational companies have access to the world’s largest and most experienced accountancy companies, they also know their business in more detail than the state they are working with. Consequently a more complicated system tends to give multinationals the upper hand.

For example, in the Sakhalin II project in Russia, the complex terms of the PSA resulted in all cost over-runs being effectively deducted from state revenue instead of from the Shell-led consortium’s profits. During the planning and early construction of the project, costs inflated dramatically. In February 2005, the Audit Chamber of the Russian Federation published a review of the economics of the project, finding that cost over-runs, due to the terms of the PSA, had already cost the Russian state $2.5 billion.

Although three PSAs were signed in the mid 1990s in Russia, they have been the subject of extreme controversy ever since. The changing view of PSAs in Russia in general also illustrates the loss of democratic control inherent in PSAs – if the government or political climate changes, the terms of a PSA cannot change to reflect new priorities. PSAs generally last for between 25 and 40 years. In Russia’s case, the rush to privatise in the early 1990s is now being questioned – but with the PSAs already in force it is impossible to rectify mistakes.

The Sakhalin II PSA is an example of a special type of PSA, which is growing in prominence. In such PSAs, the sharing of ‘profit oil’ is based not on a fixed proportion, but on a sliding scale, based on the foreign company’s profitability. The state receives only a low proportion of profit oil (or in the Sakhalin case, none) until the company has achieved a specified level of profit. Thus, states are deprived of revenue, while corporate profits are guaranteed. (See Appendix 1).

IRAQ WOULD FARE NO BETTER

In theory, Iraq may be able to negotiate PSAs with much more stringent terms than those used elsewhere in the world. As noted above, we do not know what exact terms Iraq might adopt if it uses PSAs. Iraq could also, in theory, avoid some of the more draconian legal clauses outlined above.

However, we have also seen that there are a number of structural features of PSAs which are likely to act against Iraq’s interests, whatever the terms. Helmut Merklein, a former senior official of the US Department of Energy, explains this based on the concept of economic rents – the excess profits of oil production (after deducting production costs and a reasonable return on capital):

“For all the sophistication and the bells and whistles these contracts have, … they all have two basic flaws, which make them less than perfect in terms of capturing rent. They are subject to distortions through petroleum price fluctuations in world markets, and they generally fail to provide the host country with its proper rent if the field turns out to be greater than expected. Various triggers in those agreements reduce the host country’s exposure, but they never really eliminate it.”(68)

The generation of rents is a feature of oil production. Because of oil’s sheer value, its extraction generates profits beyond what is normally expected on an investment. These rents should belong to the country that possesses the oil resource. However, Merklein’s point is that PSAs cannot – in unpredictable economic circumstances – deliver the country its fair share of the rents, and inevitably tend to give foreign oil companies excessive profits at the country’s expense.

To the flaws identified by Merklein, we would add the long-term and restrictive nature of PSAs, that their terms are fixed as negotiated in a situation which – one hopes – will not persist in Iraq; and that they also place legal constraints beyond the issue of revenue-sharing, as we have seen.

In some countries, circumstances in the oil sector may favour investment through a mechanism such as PSAs, in spite of these disadvantages – such as where fields are offshore, risk capital for exploration is required, or the country lacks technical competence. In Iraq, however, these conditions do not apply, and given the country’s huge oil wealth, it does not need to accept the negative consequences of PSAs.

On top of these structural flaws in PSAs, there are grounds to doubt whether the specific terms Iraq might achieve would be any better than in other countries, despite Iraq’s enormous oil reserves. The key issue here is bargaining power: the Iraqi state is new and weak, and damaged by the ongoing violence and by corruption, and the country is still under military occupation.

In fact, rather than negotiating a more stringent PSA deal than elsewhere, the oil companies will inevitably wish to focus on the current security situation to push for a deal comparable to – or better than – that in other countries in the world, while downplaying the huge reserves and low production costs which make Iraq an irresistible investment.

Indeed, precisely this point is being pushed by the oil companies and their governments. The corporate lobby group ITIC attempts to invert conventional economic logic, by implying that there is greater competition among oil-producing countries than among private companies:

“Although Iraq’s potential petroleum wealth is enormous, the government still faces competition from other countries offering petroleum rights to investors. … Investors, too, are competing for access to attractive petroleum deposits but competition among them may be limited if the project in question requires scarce expertise or depth of financial resources.”(69)

Thus one of ITIC’s key recommendations is that Iraq “offer to companies profit potential consistent with the risk they bear”.(70)

Their argument that countries, not companies, must compete is especially perverse given the high oil price, and the wide recognition of supply constraint: that there is a shortage of access to reserves, not of access to capital.

Similarly, the US government’s development agency USAID has advised the Iraqi authorities that

“Countries with less attractive geology and governance, such as Azerbaijan, have been able to partially overcome their risk profile and attract billions of dollars of investment by offering a contractual balance of commercial interests within the risk contract, one that is enforceable under UK and Azeri law with the option of international arbitration.”(71)

If Iraq follows that advice, it could not only concede a contractual form which is not in its interests, but specific terms which radically understate the country’s attractiveness to the international oil industry. Along with much of its future income, Iraq could be surrendering its democracy as soon as it achieves it.

6. A better deal: Options for investment in Iraq’s oil development Back to top

A central question for Iraqi planners and politicians is how to invest in the country's oilfields – revenues from which will provide the central plank of the Iraqi economy for the foreseeable future. In the last section we saw, by looking at common practice elsewhere in the world, that investment through production sharing agreements (PSAs), would be likely to come at considerable cost to Iraq.

A RADICAL DEPARTURE

Much as their proponents like to claim that PSAs are standard practice throughout the world’s oil industries, in fact International Energy Agency figures show that just 12% of world oil reserves are subject to PSAs, compared to 67% developed solely or primarily by national oil companies.(72) Thus it is far from inevitable or necessary that PSAs must be used in order to obtain investment in Iraq’s oil development.

PSAs are often used in countries with small reserves; however the nationalised model is almost exclusively used in all countries with very large oil reserves.

The use of PSAs in Iraq would represent a major departure from common practice among the large oil producers of the region. Iraq and three of its neighbours (Saudi Arabia, Iran and Kuwait) are the world’s top four countries in terms of oil reserves, with 51% of the world total between them.(73) None of them use any form of foreign company equity involvement in oilfields.

Looking further afield, these four Gulf states together with the United Arab Emirates, Venezuela and Russia, hold 72% of the world’s oil reserves. These latter three all have some foreign involvement in their oil industry, although both Venezuela and Russia are currently drawing back from it, following unsuccessful expansions in foreign investment in the 1990s. Of these seven countries with major oil reserves, only Russia has any production sharing agreements.

In the Russian case, three PSAs were signed in the mid 1990s; they have been the subject of extreme controversy ever since due to the poor deal the state has obtained from them, and it now looks unlikely that any more will be signed.

OPTIONS FOR INVESTMENT

One argument that is deployed by proponents of PSAs is that Iraq has no other option to generate the capital investment needed to rebuild and expand its oil industry.

This is simply not true. In fact Iraq has at least three options for generating investment in its oil industry, without giving away its revenue and control over the industry:

1. Direct investment from government budget.

2. Government / state oil company borrowing from banks, multilateral agencies and other lenders.

3. Investment by international oil companies using more flexible and equitable forms of contract.

It is not the role of this report to advocate any particular structure for the Iraqi oil industry, nor to advocate for or against the use of foreign investment. That decision rests with the Iraqi people. However, in this section we briefly explore each of these options, all three of which are superior to PSAs in terms of consequences for the Iraqi economy and people.

After 50 years of rip-off by foreign companies and over 20 years of war, Iraq needs the right policies to develop its oil industry.First, it should be stressed that there is considerable technical competence among Iraqis themselves and foreign companies are not required to manage the industry. Indeed, the most successful period in the history of Iraq’s oil industry was between nationalisation in 1972 and the start of the first of Saddam’s wars with Iran in 1980. Freed up from the foreign interference that had unhappily characterised Iraq’s previous petroleum history, the Iraq National Oil Company moved forward confidently and effectively: between 1970 and 1979, INOC increased production from 1.5 million to 3.7 million barrels per day and discovered the four super-giant fields West Qurna, East Baghdad, Majnoon and Nahr Umar, and at least eight giant fields.

In some areas, the state of Iraqi knowledge may not be the most up-to-date, because of the sanctions era. However, this is easily solved within any of the above models by employing specialist companies under short-term technical service contracts to provide drilling and production expertise when required. Thus what is at issue is how capital is obtained, not skills.

OPTION 1: FINANCING FROM GOVERNMENT BUDGETS

The simplest model would be for the required investment to be provided each year out of government budgets. This is quite possible and appropriate in Iraq’s case, because in contrast to many other countries:

The development cost is low when compared to the return;

As a consequence, the payback period is very quick;

Since there are considerable proven but currently undeveloped oil reserves, risk to capital is very low (as no exploration is required for immediate field development). In the longer term, Iraq will explore but even this is relatively cheap and low-risk. Iraq's investment requirement is expected to peak at around $3 billion per year.(75) This is well within the range of current budgetary allocations: the 2005 Iraqi oil investment budget is $3 billion76 (out of a total Iraqi budget of around $30 billion).

Furthermore, within at most three years from the start of development, revenues from new production would well exceed the ongoing investment requirements, and could therefore provide this finance. In other words, at worst Iraq would have to invest $2.5 – 3.0 bn of its existing budget for three years.

One argument commonly advanced in favour of foreign investment in Iraq’s oil is that it would save government budgetary expenditures for other priority areas. For example, the British Foreign Office argued in 2004, in a Code of Practice issued to the Iraqi Oil Ministry:

“In the absence of a very high oil price, Iraq would only be able to finance this investment [in oil development] itself if it could secure a very generous debt reduction deal and was prepared to make substantial cuts in government expenditure in other areas. Given Iraq's needs, it is not realistic to cut government spending in other areas, and Iraq would need to engage with the International Oil Companies (IOCs) to provide appropriate levels of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to do this.”(76)