Afghanistan as an empty space

The perfect Neo-Colonial state of the 21st century. Part one. See parts two, three and four.

by Marc W. Herold

Departments of Economics and Women's Studies

Whittemore School of Business & Economics

University of New Hampshire

This report is dedicated to the invisible many in the 'new' Afghanistan who are cold, hungry, jobless, sick -- people like Mohammad Kabir, 35, Nasir Salam, 8, Sahib Jamal, 60, and Cho Cha, a street child -- because they 'do not exist.'

POSTED FEBRUARY 26, 2006 --

Argument: Four years after the U.S.-led attack on Afghanistan, the true meaning of the U.S occupation is revealing itself. Afghanistan represents merely a space that is to be kept empty. Western powers have no interest in either buying from or selling to the blighted nation. The impoverished Afghan civilian population is as irrelevant as is the nation's economic development. But the space represented by Afghanistan in a volatile region of geo-political import, is to be kept vacant from all hostile forces. The country is situated at the center of a resurgent Islamic world, close to a rising China (and India) and the restive ex-Soviet Asian republics, and adjacent to oil-rich states.

The only populated centers of any real concern are a few islands of grotesque capitalist imaginary reality -- foremost Kabul -- needed to project the image of an existing central government, an image further promoted by Karzai's frequent international junkets. In such islands of affluence amidst a sea of poverty, a sufficient density of foreign ex-pats, a bloated NGO-community, carpetbaggers and hangers-on of all stripes, money disbursers, neo-colonial administrators, opportunists, bribed local power brokers, facilitators, beauticians (of the city planner or aesthetician types), members of the development establishment, do-gooders, enforcers, etc., warrants the presence of Western businesses. These include foreign bank branches, luxury hotels (Serena Kabul, Hyatt Regency of Kabul), shopping malls (the Roshan Plaza, the Kabul City Centre mall), import houses (Toyota selling its popular Land Cruiser), image makers (J. Walter Thompson), and the ubiquitous Coca-Cola1.

The "other," the real economy -- is a vast informal one in which the Afghan masses creatively eke out a daily existence.2 They are utterly irrelevant to the neo-colonist interested in running an empty space at the least cost. The self-financing opium economy reduces such cost and thrives upon invisibility. The invisible multitudes represent a nuisance -- much like Kabul's traffic -- upon maintaining the empty space. Only the minimal amount of resources -- whether of the carrot or stick type -- will be devoted to preserving their invisibility. Many of those who returned after the overthrow of the Taliban are now seeking to emigrate abroad, further emptying the space.3

The means to maintain and police such an empty space are a particular spatial distribution of military projection by U.S. and increasingly NATO forces: twenty-four hour high-level aerial surveillance; a three-level aerial presence (low, medium, high altitude); pre-positioned fast-reaction, heavily-armed ground forces based at heavily fortified key nodal points; and the employ of local satraps' expendable forces. The aim of running the empty space at least cost is foundering upon a resurgent Taliban, who have developed their own least cost insurgency weapons (e.g., improvised explosive devices and suicide bombings) and are putting them to good use.

U.S. troops patrolling the empty space of Afghanistan

Unlike in the colonies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries where effort was made to develop economic activities -- from plantations to mines, factories to infrastructure -- in order to have a self-financing colony, in the neo-colony of Afghanistan no such efforts are warranted. Indeed, such efforts contravene the aim of running an empty space at least cost. In effect, Afghanistan today has reincarnated itself in its historic role as a buffer state (in twenty-first century clothing).

While this argument may offend many -- from the U.S military's Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) to the United Nations development establishment (UNAMA), to the community of NGOs and to the 'Cruise Missile Left' (the humanitarian interventionists are well-represented in Kabul4) -- it nonetheless presents a coherent whole of what we have seen and continue to see in Afghanistan. Laments and mea culpas about "nation-building on the cheap" miss the entire point -- empty space on the cheap. The argument, which is constructed based upon revealed outcomes -- or circumstantial evidence -- as nowhere would any of the powerful or their lackeys publicly admit that Afghanistan is an empty space, is comprised of five inter-related sections, the first two of which are included in this essay. I document how the United States and its client state in Afghanistan, has no interest in real socio-economic development in Afghanistan, and delve into the largely invisible economy where most Afghans carry out a daily struggle to survive. Part two will expose the grotesque forms of pseudo-development in Kabul, reveal how an illusionary image of progress and governance -- Brand Karzai - is constructed and marketed, and close with an analysis of the U.S. military strategy, which is geared to protect at least cost an "empty space," a modern reincarnation of the buffer state.

Real development is an after-thought

In 1989/90 when Afghanistan had served its 'external' purpose -- defeating Soviet forces and weakening the Soviet Union -- U.S. interest faded and the country became an "empty space" though with dire medium-run consequences (in the guise of Osama bin Laden disembarking in Jalalabad in 1996, at the invitation not of the Taliban but by their enemies, mujahideen warlords whom the U.S. had funded and armed5). Similarly, during the period 1950-79, Afghanistan was of no interest to U.S. policymakers so long as the country's leaders maintained its neutrality during the Cold War, something carefully pursued in those decades.

Afghanistan is of no economic interest either in terms of what it exports legally (dried fruit and carpets) or as a market for imports and foreign investment. One can only look on with some bemusement as the Western development establishment searches feverishly for legitimate "new" exports, both as substitutes for opium, and to contribute to righting a huge trade deficit. High-value products like cut flowers, saffron, rosewater, lavender, and perfumes have been suggested as substitute crops6. But even the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization dismisses the saffron idea, noting that it might grow in the Maiwand district of Kandahar, "...but fits into a different agricultural niche than poppy and is simply not a viable alternative."7

Such views conveniently forget that the country's economy has historically been based upon self-sufficiency and subsistence agriculture, centered upon the clan at the village level.8

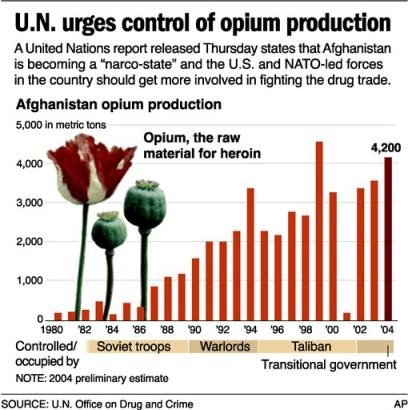

The exponential rise in land devoted to opium poppy production since 2001 is a very clear indicator of peoples' revealed options or preferences in terms of survival opportunities. Year-end 2005 estimates indicated that more than 2 million Afghans, about 9 percent of the population, grew opium illegally. Focus upon land under cultivation, however, can be misleading if per acre yields vary as they did during 2003-4 when bad weather and crop infestation significantly reduced yields. In 1999, under the Taliban, 4,600 tons of opium resin were produced compared to 4,200 tons in 2004. In 2003, total output was about 3,600 tons with a hectare yield of 45 kilos of opium, which brought in a farm gate price $283 a kilo (but only $92 in 2004, though, as The Economist noted, "...still not bad, when GDP per head is around $2009). The average kilo farm-gate price of opium in 2005 was $102 (a kilo of heroin sold for $60,000 on the streets of Moscow.10) Yields have since risen -- 32 kilos per hectare in 2004 to 39 kilos in 2005 -- an increase in acreage yield of 22 percent attributed greater moisture and no crop infestation. While the Western press points to the "success" of efforts in combating poppy production by highlighting a decrease in acreage between 2004-5 from 131,000 to 104,000 hectares, overall opium output in 2005 remained at 4,100 tons11. The prospects are for a continuing flourishing poppy trade.12

Source: "A New Opium War"

Again, all the official hand-wringing in the West about Afghanistan's opium economy and the heralding of alternative crops fails to understand that the opium crop unlike any other is at the center of a complex web of village social relationships. It forms the glue in a complex network of relationships of reciprocity. Peasant farmers do not engage in poppy growing merely because of higher returns per hectare.

Poppy growing and opium production have a long history in Afghanistan. In the 1930s, a quasi-state enterprise held a monopoly of opium export (as recounted elsewhere herein). In much contemporary writing, a flawed, crude, reductionist argument is made: profit-maximizing Afghan farmers will opt to grow poppies. Such a simplistic analysis is untenable.

David Mansfield has presented an incisive, nuanced analysis of opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan based upon field research from June 1997 to December 199913. Mansfield begins by noting that the extent of poppy cultivation differs widely across districts in Afghanistan, being greater in areas where landholdings are small, access to both irrigation water and markets more difficult. Poppy mono-cropping is basically non-existent.

In effect, poppy growing is determined by specific local conditions and is not necessarily a profitable crop in all circumstances. In particular, poppy growing emerges as a bargain amongst unequal parties, that is, "it has become a medium of exchange between the resource rich and the resource poor, creating a symbiotic relationship." He elaborates,

For the resource rich, their control over resources allows them to determine the rules of exchange by which they acquire opium. Consequently, traditional land tenure arrangements and informal credit systems have been modified in order to favor the cultivation of opium poppy. Within this new framework, opium has come to represent a commodity to be exchanged, not only for the purchase of food but as the means for achieving food security, providing the resource poor with access to land for agricultural production and credit during times of food scarcity.

Hence, opium production is driven less by expected profitability (and crop substitution calculations) and much more by the livelihood strategies of the poor, as it provides access to land, credit, and a vital source of off-farm income necessary for household survival. On the other hand, for those with land, opium cultivation generates attractive risk-adjusted return with minimal personal effort. As Mansfield so aptly concludes, one need recognize that the socio-economic and political structures that create and maintain poverty in Afghanistan also encouraged the cultivation of opium poppy.

A similar conclusion was reached by a leading researcher at France's Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique who emphasized that opium production proceeds from poverty and food insecurity, from Afghanistan to Myanmar.... it is a coping mechanism and livelihood strategy,

...providing peasants not only with a source of income, but also with access to land and credit. More than opium production as such, it is therefore poverty and the shortcomings of the Afghan agrarian system that should be tackled.14

Much ado is made in the West about opium being in the hands of the Pashtun Taliban. Again, such a perspective conveniently forgets the contrary evidence presented by the province of Badakshan where the Taliban never had any presence. The Western-sponsored poppy eradication programs have primarily served to alienate large swathes of the desperately poor Afghan rural population who depend upon poppy for daily survival.15 The U.S.-organized effort in 2004 was a resounding failure. The U.S. contracted with DynCorp (a favorite of Team Bush) for $50 million to train an Afghan eradication team. The 400 members received two weeks' training -- long enough, according to one diplomat then, "to learn how to drive a tractor and point a gun." The team set out for Wardak Province. The result was chaos. In the words of The Economist,

farmers fired rockets at the team camp, and sowed their poppy fields with land mines. Yet it destroyed 1,000 hectares of poppy in six weeks, and should be expanded next year.16

Similar resistance and anger at Western-led efforts to eradicate poppies arose in Nangarhar province. While poppy output was reduced by 80 percent,

Villagers estimated that 60 percent of Hafi Zan's economy had disappeared. The local mason, butcher and fruit seller have all gone out of business. 'Our village has lost almost all its income,' said one of the elders in another village near the Pakistan border. 'We have no choice. This coming year [2005-6] we will plant opium again and this time the whole tribe is agreed that we will fight. We are ready to die.17

The income from drugs during 2002-2004 is estimated to have been $6.820 billion, while that from international aid was less than half that, $3.337 billion.18 Whereas pledges of aid from the international community between January 2002 -- April 2006, amounted to $14.4 billion, only $9.1 billion were actually committed by February 2005, and of that only $3.9 billion disbursed (January 2002 -- February 2005) and $3.3 billion has been disbursed for ongoing projects. Of the total disbursements, a mere $.9 billion worth of projects have been completed. Such fine points escape many who point out that Afghanistan "...has been supported by an input of about $15 billion dollars from the international community since 2001."19 Ahmed Rashid reported that western donors committed on average $2.5 billion every year during 2002-5 for reconstruction, but less than half that money was disbursed20. For its part, the U.S. has spent $1.3 billion on reconstruction in Afghanistan over four years, "intending to win over Afghans with signs of progress."21 By way of contrast, the United States spends $10 - $12 billion annually on military operations in Afghanistan.

The World Bank and members of the development establishment like to point out that such meager results are explained by "bottlenecks in implementation" -- long times between commitment to a project and start of actual work. A study sympathetic to the so-called reconstruction effort in Afghanistan was forced to admit in early 2005,

...growth of the legal economy has slowed, little investment is arriving, even Kabul has no reliable electric power or water supply, and bureaucrats paid less than $50 a month in a capital [city] where the housing market caters to internationals to pay $10,000 a month for a house, resist reforms that they fear might throw them out on the street...22

At the same time, such "development experts" and representatives from some NGO's like CARE, point out that Afghanistan has received significantly less international aid (per capita) than other post-conflict societies (like Kosovo, East Timor, Bosnia, etc)23. They then go on to blame such a low level of funding as explaining why in the eyes of many Afghans, so little reconstruction has taken place. The refrain is familiar. James Dobbins, a former Bush envoy to Afghanistan, says

Afghanistan is the least resourced, large-scale American reconstruction programme ever.24

Whereas certainly a low level of international funding in relative terms has occurred -- hardly surprising given Afghanistan as an empty space -- more important has been what and how the funds have been spent. As one story headlined, "...computers, satellites and money cannot in themselves transform an impoverished tribal society," especially combined with rampant corruption, inflated project costs and poor carry-through.

During 2002-5, the U.S. spent about $1.3 billion -- or some 38 percent of the total $3.6 billion pledged by the international donor community after 200125 -- on Afghan reconstruction (as compared to $30 billion in Iraq), that is, a little over $250 million per year, a paltry amount. Moreover, the Bush administration has slashed reconstruction aid to Afghanistan from $1 billion in 2005 to $623 million in 2006. Afghans are widely reported to being increasingly disenchanted with the U.S.-led reconstruction program. Projects languish unfinished, and project quality leaves much to be desired. For example the U.S.A.I.D. in 2004 budgeted to build or renovate 289 schools, but U.S. contractors built only eight and refurbished 77, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Likewise, the U.S.A.I.D. budgeted to build or rehabilitate 253 health clinics in Afghanistan; eight were built and none were rehabilitated. The GAO pointed to poor contractor performance (and security problems, inconsistent financing, staff shortages, lack of oversight).26 Other reports echo the concern over the poor quality of work undertaken. For example, in a village close to the U.S. occupation forces' main base at Bagram, a mud-brick school built in 2003 compliments of American taxpayers is now in utter disrepair -- its walls crumbling and its roof pitted by termites chewing into untreated wooden beams.27 Moreover, the project costs of official U.S.-sponsored projects are often much higher than by a private NGO. For example, CARE International built 40 schools in 2004, which in most cases cost $10,000 - $20,000 less than U.S-sponsored projects.

The chief U.S.A.I.D. administrator in Kabul, however, proclaims that much progress has been made, citing two national elections, five times as many children in school (including 1.6 million girls), and 500 miles of asphalt roads. Similar rationalizations get regularly repeated: a legal economy which has grown 85 percent since 2001, a quadrupling of school enrollments to 6 million pupils (one-third of whom are girls), falling inflation, a stable currency, booming urban commerce, and paving 1,740 kilometers of roads. Another purveyor of glad tidings from Afghanistan is, predictably, The Wall Street Journal.28

The use of Provisional Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) by international military forces in Afghanistan to engage in civilian reconstruction projects has consistently been criticized by NGOs on three grounds: quality of work executed; high cost of work executed; and concern that blending military and civilian operations will heighten insecurity for all civilian reconstruction work -- a claim well borne out as reconstruction workers have become targets since 2002.29 Moreover, PRTs seem to have come about as a way of trying to achieve security in Afghanistan on the cheap.30

All this does little to alleviate rural hunger, provide jobs, increase access to clean water, etc. In an interview in mid-2005, Afghanistan's Minister for Rural Development, Mohammad Hanif Atmar, admitted that most of rural Afghanistan simply continues to suffer from food insecurity, little access to safe drinking water, access to basic social services such as health and education, etc.31 Generally, aid bypasses needy villages, whereas in some towns monies sent by relatives from abroad stimulates economic activity.32 Even in Kabul, the island of Westernization and the epicenter of imaginary reality, garbage piles up (generating foul odor and undoubtedly contributing to disease) as the city is only able to remove 40 percent of the daily waste produced.33 The city's sewage difficulties are even worse. Kabul, which never had a sewerage-pipe system, has but one truck for picking up sewage! Most property owners simply pay for men with donkey carts to take sewage away. But those too poor to afford that, suffer disproportionately from diseases such as leishmaniasis (a sin ailment caused by a parasite transmitted by sand flies), mumps and diarrhea due to garbage and sewage problems. High levels of dust, soot, and fumes also choke Kabul, causing health problems.34

But the problems run deeper than low funding, "bureaucratic bottlenecks" which paralyze aid donors, and poor project implementation. Spending upon luxury high-visibility constructions in the few urban centers and major highways -- a favorite of the international community -- has very little direct benefit to most Afghans who live outside of cities and far away from major highways. Over $3 billion in reconstruction has not brought one single new power plant, new dam, or major water system into service even though electricity is an important input in cities and for agriculture. An estimated six percent of Afghans receive any regular electricity.35 Road construction has bypassed rural areas where roads are most needed. A doctor in the Guzara district of Herat province told a Los Angeles Times reporter that many pregnant women die on their way to hospitals because they lack transportation or the secondary roads are impassable.36 But the high visibility U.S-funded Kabul to Kandahar $250 million highway was paved by the Louis Berger Group as chief contractor in record-breaking time, with the aim of helping Karzai in the June 2004 elections and providing for many photo-ops, dutifully printed in the U.S. corporate media. In late 2003, a U.S. program named "Accelerate Success" was launched in Afghanistan, "geared towards reshaping the Afghan public perception of both the Afghan central government and the United States, its major supporter."37 The critical element was to create the image -- the perception -- that U.S.-led efforts are improving peoples' lives. Even Jim Myers, head of Louis Berger's Afghan operations said in October 2004, "it's the most political project I've ever done."38

Source: "Karzai Opens Key Afghan Highway," BBC News (December 16, 2003)

Another common complaint amongst Afghans is that they are left out of much of their own rebuilding.39 For example the Chinese-funded project to rebuild the Kabul-Jalalabad highway went to two Chinese firms, relying upon expensive, skilled foreign labor. A similar claim is made about the United States, which favors U.S. firms for its projects:

According to the Washington Post, U.S. construction company, Louis Berger has built or renovated 533 buildings, including clinics and schools at an average cost of 226,000 dollars each. The Afghan government could have done the job for 50,000 dollars a unit, the paper said.40

As far as private aid through the 2,300 and some NGOs -- 400 being international -- active in Afghanistan, which both receive and channel aid, they perform governmental functions that under-sourced Afghans should be doing. Maintaining this maze of NGOs is wasteful. Their logistics, personnel, housing and other internal costs eat up more than 60 percent of the assistance money, a figure that is probably somewhat exaggerated. Afghans reportedly joke

...that they suffered under the Soviets, then the Taliban and now the NGOs.41

The question is where is all the money going in Afghanistan?

Karzai's Planning Minister, Ramazan Bashardost, in 2004 specifically took the NGO community to task, but also the United Nations, accusing them of wasting billions. As planning minister, Bashardost was chief supervisor to the aid organizations operating in Afghanistan. He sought to clarify how the NGOs were actually spending the money allocated to them -- how much for the rents and salaries, for their cars and how much they were actually using for their projects. He demanded the organizations open their books. Only 437 out of a total of 2,355 organizations obliged. He found that many relief organizations were there for a simple reason: to turn a profit by the working the gold mine of lucrative aid contracts. The phrase "NGO mafia" is commonly used.

Bashardost resigned when his efforts were overruled by the Western kowtowing Karzai, but he then went on to win a seat in the parliamentary elections with one of the highest numbers of votes in Kabul. Barshardost said,

the people are asking themselves if these billions of dollars have been donated, which of our pains have they remedied, what ointment has been put on our wounds... there is minimum improvement in the lives of ordinary people... all ministers and key government officials have lost their legitimacy.42

His parliamentary campaign called for 1,935 registered NGO's to be expelled from Afghanistan. He says about 20 percent of all funding to NGOs is spent on "commissions" which are bribes to government officials (and the U.N. behaves similarly). He also points out that 420 of the NGOs in Afghanistan have done excellent work.43

Bashardost's critique was largely ignored in the United States, but Der Spiegel devoted a lengthy article in 2005 to the topic of "the aid swindle."44 Susanne Koelbi echoes many points I had made in an essay published in late 2004 for Cursor.org.45 She writes,

The international community has sought to deliver quick success in rebuilding war-torn Afghanistan. But the country has become an El Dorado for international consultants and professional aid workers who ply the streets in Land Cruisers. Their methods have also fostered an atmosphere of corruption and sloppiness that has left many Afghans feeling disappointed and cheated.

The aid "wastage" -- hefty salaries, luxury cars, large overheads, 'commissions,' overpricing, corruption -- was also noted by Jean Mazurelle, World Bank director in Afghanistan, in January 2006,

In Afghanistan the wastage of aid is sky-high; there is real looting going on, mainly by private enterprises. It is a scandal...In 30 years of my career I have never seen anything like it.46

He goes on to say that 35-40 percent of the aid is "badly spent," funding a plethora of international consultants and security for expatriates. And some of the aid pledged to Afghanistan is used to maintain head offices in faraway capitals. For example, "aid consultants" placed in government and non-government offices -- all the American and NATO "advisers" who from behind their walled compounds "weigh in on every aspect of governance, from what kind of uniform the new border police should wear to the legal details of a huge new anti narcotics law"47 -- take 15 to 25 percent of total aid according to estimates.

For example, a European official reported

For a contract of 45 million dollars recently given to the F.A.O., four million has to go towards financing its headquarters in Rome.48

The Karzai regime officeholders seek to have the aid disbursements go through the Afghan government -- three-quarters of foreign aid to Afghanistan in 2006 was not going through the government.49 Of course, given the high levels of official corruption and nepotism within the Karzai clique (a theme I shall later address)50, such a "reform" seems to trade-off monies flowing to expensive foreign aid contractors for monies flowing into the pockets of Karzai's clique (via kick-backs on contracts, etc.).

Even the Minister of Economy, Amin Farhang, who overseas foreign assistance programs reportedly observed in December 2006,

"assistance is coming to Afghanistan, but we don't know how it is spent, where it is spent.51

What better description of Afghanistan as empty space to be kept that way "on the cheap."

The situation for Afghan women and children was deemed an "acute emergency" in mid-2005 by a representative of UNICEF due to sky-high maternal death rates and almost one-half of all children -- particularly girls -- suffering from malnutrition.52 The winter of 2004-5 exposed the country's broken promises when more than 600 people, most of them children died. In some eastern provinces, ravenous wolves attacked hungry children.53

A virtual fetish has been made of bringing education to Afghan girls and women, a cause taken up in some feminist quarters. Again, the transparently obvious political dimension is clear for all to see.54 The 2004 UNDP report on Afghanistan notes that it "has the worst education system in the world." Why did Western donors before 9/11 express no interest in the plight of Afghan women or girls' education? Why did they not support and report widely upon the lonely, tireless efforts of RAWA?55 Why do these donors who care so much for Afghan girls, not express similar concern for poor African women? A study made two years after the U.S. invasion concluded,

Yet, more than two years later, the number and manner of dollars spent, and the actual situation on the ground reveals that Afghan women's rights have been clearly negotiated in exchange for political gains, manipulated for public relations success stories, under-funded, or ignored altogether.56

Abundant further evidence has been collected by R.A.W.A. demonstrating that change for Afghan women has been at best marginal since the U.S. invasion.57 As a member of R.A.W.A. wrote,

Britain and the U.S. said war on Afghanistan would liberate women. We are still waiting... The Karzai government has established a women's ministry just to throw dust in the eyes of the international community. In reality, this ministry has done nothing for women. There are complaints that money given to the women's ministry by foreign NGOs has been taken by powerful warlords in the Karzai cabinet.58

In what surely qualifies as a major public relations coup -- widely picked up in the Western corporate media -- a beauty school was set up inside the Ministry of Women's Affairs in Kabul. The funding was provided by a group of "comfortable New Yorkers in the high fashion industry," including a Vogue Editor.59 The ostensible purpose was to train local women in beauty techniques and to give them the business skills to set up their own salons, but the effort was re-interpreted by the West as an example of women's liberation (though the BBC sarcastically headlined a story "Afghan lipstick liberation"60), when in fact the group benefited represents an infinitesimal fraction of Afghan women.

Another way to expose the negligible value put on the lives of common Afghans is simply to peruse the detailed evidence I have been gathering during the past four years on the killing and injuring of thousands of Afghan civilians carried out in the name of a 'war on terror.' My compilation, the Afghan Victim Memorial Project, provides up-to-date details on the killing of more than 1,300 Afghans.61 Another angle to document the low value put on an Afghan's life is to compare the compensation paid by the U.S. military in cases of wrongful death.62

I have argued that Afghanistan is simply of no economic interest to the United States (and other developed countries). This is revealed by very low levels of reconstruction aid provided and by the types of donor-funded projects implemented, driven more by donor interests than concern for Afghans' everyday lives. Much of the reconstruction aid has been devoted to high visibility projects of questionable value to average Afghans. The Afghan masses are increasingly clear that terribly little of the $3 billion in reconstruction aid has trickled-down to them, whereas a significant portion has manifestly and visibly tricked-up to the coterie of elites around Karzai, comfortably ensconced in Kabul.63 But, should we expect otherwise when the country's function is that of an empty space to be maintained at least cost and presided over by the imaginary reality of a government in Kabul?

The lives of the masses don't matter

The "new" Afghan economy is primarily a jobless one, where returned refugees are now seeking to leave once again. It is also dependent upon and driven by imports, and dominated by the opium trade, where the economic gains are very unequally distributed.

Overflowing slums of Kabul, a vast casual labor market, begging, children everywhere trying to earn a few pennies, and visible rampant poverty provide the evidence not available in non-existent official reports. In December 2004, the United Nations' International Labour Organization drew attention to high levels of unemployment in Afghanistan.64 It singled out illiteracy (estimated to be 70 percent) as the single greatest cause, but that really misses the point. Widespread unemployment results from a stagnant real economy -- the reported annual economic growth rates of 10-20 percent are statistical constructions having little to do with the real economy of producing legal goods and services. The vast bulk of Afghans find occasional or casual employment in the informal economy in cities or the countryside. Around 50,000 children in Kabul -- or two percent of the city's population - work on the streets polishing shoes, selling fruit, working as porters in the markets, washing cars, scavenging in garbage, or simply begging for money.

Children in Kabul collecting garbage for resale, March 2004

For example, Mohammad Kabir, 35, who was sacked from a government job in a reform process, told IRIN news as he waited at the crowded roundabout at Kot-e-Sangi on the outskirts of Kabul, a huge informal labor market,

This is the capital and you can guess [what it is like in] the provinces. All these people gather here every morning expecting to find daily labor and earn some bread and tea for the family meal.

He waited until midday before finding a half a day's work.

Others find work as servants, chauffeurs and bodyguards in the new service economy of Kabul.65 Yet others find temporary jobs in the booming luxury construction taking place in Kabul -- building five-star hotels, shopping malls, narco-mansions or "corrupto-mansions."

Others conclude, "The new Afghanistan is a myth [and] it's time to go and get a job abroad." As Dan McDougall wrote recently,

Outside the iron gates of the Iranian embassy, braced against the winter sleet in woolen caps and ankle-length chupans, hundreds of Afghan men roll out blankets and kneel towards Mecca. At each bow the men's noses merge with the slushy grey mixture of mud, snow and sewage that covers the rutted pavements and roads of Kabul. Their prayers are for a new life elsewhere and food for their starving families - they are queuing in the dawn's half light to leave Afghanistan.... 'I wish I hadn't come back home from Iran after the Taliban left. I had a better life there; I had occasional work at least, so I am going back.' Zahair Mohammad stands in the line trying, with hundreds of others, to get an Iranian visa. 'I was thinking positively for a long time about rebuilding a life here in Kabul, where I was born, but I was wrong, very wrong. It's time to go. I need to work abroad, like most, as a cheap labourer and send money home. What we're hearing on the radio about a new Afghanistan is nothing but a dream.' He gestures at the kilometre-long queue. 'I was a refugee before and now I'm choosing to become one again. I'm not alone.... The Observer has learnt that such is the demand among ordinary Afghans to leave that this weekend the Interior Ministry has run out of the basic materials to make passports...According to human rights watchdogs, the huge increase in economic migrants exposes the shortcomings of Western-led reconstruction, estimated to have cost $8bn (£4.5bn) so far, failures which are disturbingly apparent in the overflowing slums of the capital, Kabul. Hundreds of thousands may have returned from Pakistan and Iran, swelling the city's population to more than two million, but with local unemployment running at 70 percent there is simply no future for them.'66

Others estimate the unemployment rate in Kabul's population of 2.5 million at 50-70 percent. While the country's gross domestic product has nearly doubled since 2001, about 30 percent of the country's population remains unemployed -- the unemployment rates in the countryside are much lower -- and 37 percent need donated food to survive according to statistics compiled from the Brookings Institution.67

No aggregate figures are available which describe this reality of a jobless real economy without hope. Certainly a vibrant informal economy exists in which boundless creativity thrives and softens the daily hardship of surviving, but this economy exists outside of and in spite of that created by the technocrats of the development establishment. In this city without industry, with streets abounding with beggars, with hundreds of thousands of impoverished widows and orphans, with chaotic traffic jams (some 30,000 find jobs driving taxis in Kabul), and poverty wages, the option of leaving looks attractive. I can do no better than cite McDougall,

In the bombed remains of Kabul's Ministry of Energy, Nasir Salam, aged eight, skips through the mud, his jacket flapping in the wind, exposing his skinny ribs. He is running towards a vast mound of rubbish where children are playing with kites, one of Afghanistan's most popular pastimes, although the kites are composites of plastic bags and greasy lengths of string. The youngsters are badly malnourished, their hair and flesh a mass of sores. their chests wheezing. On the road that runs parallel to the slum, their mothers congregate, dressed in filthy burqas and chadris, eyes visible through latticed slits as they bang on car windows begging for money. Others like them had earlier caught a bus to beg in central Kabul, hoping that passing aid workers will spare a dollar. Idle men are everywhere, standing in small groups amid creeks of raw sewage.

Nasir and his parents are among hundreds of families who have taken up residence in this abandoned compound - most were refugees, encouraged to return home from Iran or Pakistan, after the fall of the Taliban but now destitute. The buildings where some are squatting have collapsed ceilings, but they offer some respite from the cold. Few charities come here. The only visitors in the past month have been officials from a government ministry who came to inspect the site and said they would evict the squatters and reclaim the land for the state.

Nasir's father, Allahnazzar, 47, says he would leave, if he could. 'What is there for us here? There are hundreds of thousands like us, perhaps millions. There is no work. We are squatting in the corner of a bombed building for shelter, there is no clean water and children die from disease here every month. Many friends who were with me in Pakistan after the Taliban took power have gone back to find work as labourers. Abroad they can work and send money back to their families to help them survive.' In a far corner of the slum, 20-year-old Enayatullah Khan has invited neighbours to his 'home' for a celebration. He is clutching his Afghan passport, empty save for an Iranian visa. He is due to leave the next day. 'I know I will earn money in Iran, I will get work as a labourer and with spring coming I will work in the fields. I am young, I don't mind leaving Kabul, most of my friends have gone.'

Outside the Ministry of Interior, a cottage industry has sprung up supplying services to those who want to leave the country, from roadside photographers providing passport pictures to local people filling out forms for the illiterate. Tariq has raised the money to buy an ancient camera and takes at least 200 passport snaps a day. 'The demand is high. Everyone wants to go to Iran and Pakistan to work, young and old, nobody wants to stay here. The queue for the visas is so large that the traffic police marshal it. But what you are seeing here is the people who want to enter within the law, probably because they have been put in jail as illegal immigrants before and don't want that again.

'Hundreds of thousands more will go over the border illegally, what other option do they have,' he adds, pointing across the street where a group of men have monopolized a playground. 'Look at them, they are playing on a children's roundabout, there is nothing else to do.'

A major contributor to the jobless economy is the import-dependency of the new Afghanistan. Aggregate trade data reveals enormous balance of trade deficits amounting to one-third of gross domestic product. As a share of the country's gross domestic product, imports amounted to: 67 percent in 2001/2, 59 percent in 2002/3, and 74 percent in 2003/4.68 The governor of Afghanistan's central bank, Anwar ul-Ahady, singled out consumer goods in 2004 as the most secure area for investment, noting

Most of the things we consume come from the outside. And major cities are the largest consumers. Kabul especially is the largest consumer.69

Since so little of that consumed in the westernized enclave economy is produced locally, all needs to be imported. Pankaj Mishra describes a Kabul scene he saw while walking back to his hotel in early 2005,

Earlier that evening, I had seen two Afghan girls at a pizza parlor. They wore tight blue jeans, their faces were uncovered, and they sipped [imported] Pepsi-Cola as they watched American women playing softball on ESPN. They would have been an unthinkable sight in the Taliban-ruled Afghanistan I had visited in early 2001. Almost four years later, Kabul was full of such surprises: new walled-off villas with mock-Palladin facades, well-stocked supermarkets, Internet cafes, beauty parlors, restaurants, and stores selling DVDs of Bollywood as well as pornographic films. Sitting in one of Kabul's great traffic jams caused by the [imported] Land Cruisers, surrounded by the vivacious banter of Afghanistan's new radio stations and the cries of children hawking newspapers, I often felt as if I was in a small Indian city...70

Kabul: the Import Economy

The spaces and activities of daily living for the masses of poor are being constantly shrunk. In one of the major scandals that came to light in September 2003, dozens of homes of poor squatters in the Sherpur neighborhood of Kabul were bulldozed to make place for "narco-mansions" and "corrupto-mansions" of the Karzai clique (including seven cabinet members and Karzai's hand-picked mayor)71. The Karzai government through its appointed mayor of Kabul, sold 4,300-square-foot lots to officials and commanders for about $1,000 each. Kothari said some were resold for more than $80,000 in Kabul's hot real estate market.72

No one in Kabul's new 'land mafia' was ever prosecuted for fraud. The issue was of such enormity that even the flaccid U.S. mainstream press took note,

"What happened in Sherpur is a microcosm of what has been happening all over the city and the country," said Miloon Kothari, a U.N. specialist on housing and land rights, who spent several weeks here. His final report accused several senior Afghan officials, including the powerful defense minister, of active collusion in official land grabs, and flatly recommended that they be fired. In his report, Kothari described a 'culture of impunity' in which Afghan officials and other powerful individuals can seize homes and refuse to leave them or appropriate valuable public land for their own profit.73

The huts were bulldozed by Kabul's police and the land parceled out to people with money and connections. Now, dozens of mansions are being built there. These "corrupto-mansions" differ from typical Afghan homes that have muted colors, simple materials, and shrouded windows. The new houses seem designed to attract attention with vivid tiles, elaborate balconies and ornate columns. A 10-foot-high eagle statue perches on one roof, wings outstretched.74

New mansions arising in the Sherpur district

In Jalalabad, Nangarhar Province, government policy led to the closure of some seventy-five brick kilns and the unemployment of 18,600 laborers.75 The government banned the import of cheap coal from Pakistan, and Afghan officials then increased domestic prices (by some 50 percent). Increased costs significantly reduced demand for mud bricks -- a staple in popular housing construction. The kilns had been operated by Afghan refugees who had returned from Pakistan, but who are now trying to collect the money to go back there. Kabul's small manufacturers of clothing and shoes -- often with ten years experience in their trade -- began closing-down in early 2005 as Kabul free-trade oriented Western policymakers allowed cheap Chinese imports of basic consumer items.76 Tamin, 22, a newly unemployed tailor who has been making suits in Kabul for ten years, says he cannot find work, adding "If I Don't find work, I will have to go to Iran."

By far the most dynamic sector of the post-Taliban economy has been the narcotics sector. By 2004-5, it was conservatively estimated to account for about 60 percent of the country's legal GDP excluding opium (compared to about 40 percent in 2001-2)77. Afghanistan has become far more dependent upon narcotics-related income (defined as the sum of farming and trafficking income) than any other country in the world -- with narcotics-related income hovering at around 60 percent of legal GDP, as compared to slightly over 20 percent for second-placed Myanmar/Burma.78 But the share of opium-related income accrues disproportionately to the traffickers:

| Year | Farmers' income (%) | Traffickers' income (%) | Total income in % | and $ billions |

| 2000 | 11% | 89% | 100% | $ .9 billion |

| 2001 | 7% | 93% | 100% | $ 1.18 billion |

| 2002 | 51% | 49% | 100% | $ 2.35 billion |

| 2003 | 43% | 57% | 100% | $ 2.3 billion |

| 2004 | 21% | 79% | 100% | $ 2.8 billion |

| Source: derived from UNODC estimates in Rubin, Hamizada, Stoddard (2005), op.cit.: 24 | ||||

The opium trade is estimated to employ 2.3 million Afghan farmer family members (compared to 1.7 million in 2003). But, farming families are capturing a declining share of total opium-related domestic income in Afghanistan -- the share falling from 51 percent in 2002 to 21 percent in 2004. A case study of the effects of the opium eradication program in Nangarhar during 2004-5 revealed a very grim picture:

This study looks at the impact such a reduction in opium poppy cultivation has had on rural livelihoods strategies and how households have responded. It explores the diversity of coping strategies households have adopted in response to the shock Theban on opium poppy cultivation has imposed on rural livelihoods in the province. It suggests that the majority of households in the areas where opium poppy has been cultivated at its most concentrated have endured significant hardship. The loss of on-farm income, combined with the daily wage labour opportunities from working during the weeding and harvesting season has led to reductions in household income of perhaps as much as US $3,400, equivalent to as much as 90 percent of their total cash income. Further indebtment of the farmers is a consequence. This fall in income has been compounded by a shift to wheat for consumption rather than high value vegetable crops fop sales, restrictions in the availability of credit, and deflation in the non-agricultural rural economy that has reduced both the level of employment and the rates of daily wage labor.79

No matter. The empty space of Afghanistan was perceived to have been violated insofar as the opium trade was believed to be financing a resurgent Taliban.

The three brief cases discussed here -- the jobless economy in the new Afghanistan, the displacement of poor families in Sherpur to make way for corrupto-mansions of the Karzai elite, and the destruction of livelihood strategies for impoverished opium farmers -- illustrate the U.S. and its client government's disinterest in the masses' real economy and daily life.

To be continued.

Footnotes

1. Naturally in the midst of this, a few organizations (and

individuals) genuinely try and do succeed in making life better for

the common people - for example, the hospital run by the Italian

N.G.O., Emergency in Kabul comes to mind, the wonderful work on

de-mining carried out by a number of NGO's, the vaccination campaigns

administered by the United Nations, the projects of Oxfam, BRAC and

RAWA, etc. .

2. For an interesting, balanced, first-hand description see Pankaj Mishra, “The Real Afghanistan,” The New York Review of Books 52, 4 (March 10, 2005)

3. Admirably put recently in Dan McDougall, “‘The new Afghanistan is a myth. It’s time to go get a job abroad’,” The Observer (February 5, 2006)

4. After the failed hunt to capture bin Laden “dead or alive,” the United States fell back upon justifying the bombing and intervention in Afghanistan upon “humanitarian grounds,” namely deposing the repressive Taliban. Many NGOs – including liberal organizations quickly came to support the U.S. intervention (see Walden Bello, “Humanitarian Intervention: Evolution of a Dangerous Doctrine,” Focus on the Global South (January 19, 2006) )

5. Kathy Gannon, “I is for Infidel,” GL Weekly (Australia) (December 4, 2005)

6. Seee for instance Barnett R. Rubin, “Flowers for Afghanistan” (Kabul, September 12, 2003)

7. FAO Representation in Afghanistan, ”Profiles: Southwestern Afghanistan. Main Crops and Cropping Systems,” FAO Website.

8. A point elaborated upon in detail in Marc W. Herold, ‘Modernizing’ Afghanistan: How 80 Years of Intervention Impoverished a Frugal Society (Durham: book manuscript-in-progress, Department of Economics, University of New Hampshire, 2006)

9. “After the Taliban,” The Economist (November 18, 2004)

10. Chouvy, op. cit., and Guy Falconbridge, “Russia Illegal Drug Trade Worth $15 Billion a Year,” Reuters (February 17, 2006)

11. Asian Development Bank, “Afghanistan’s Opium Economy,” Asian Development Bank Review (December 2005)

12. Carlotta Gall, “Afghanistan’s Openly Flourishing Poppy Trade,” New York Times (February 17, 2006)

13. See his "The Economic Superiority of Illicit Drug Production: Myth and Reality. Opium Poppy Cultivation in Afghanistan" (Feldafing/Munich: paper presented at the conference, "The Role of Alternative Development in Drug Control and Development Cooperation", August 2001)

14. Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy, “Afghan Opium: License to Kill,” South Asia (February 1, 2006)

15. For an excellent empirical account, see Christian Parenti,” Afghan Poppies Bloom,” The Nation (January 24, 2005)

16. “After the Taliban,” op. cit.

17. Tom Coghlan, “Afghan Opium Farmers’ Anger at West Threatens Crop Controls,” Telegraph (August 31, 2005)

18. Data from Barnett R. Rubin, Humayun Hamidzada and Abby Stoddard, Afghanistan 2005 and Beyond. Prospects for Improved Stability Reference Document (The Hague: Conflict Research Unit, Netherlands Institute of International Relations “Clinendael,” April 2005), 79 pp.

19. As in Sanjay Suri, “Develop the Place, For Everyone’s Sake,” Inter Press Service (January 245, 2006)

20. Ahmed Rashid, “It Takes Two Hands to Help,” Yale Center for the Study of Globalization (October 9, 2005)

21. David Rohde and Carlotta Gall, “Afghans Allege Reconstruction Funds Wasted,” New York Times (November 7, 2005)

22. Rubin, et. al., op. cit.: 63

23. Barnett R. Rubin, Abby Stoddard, Humayun Hamidzada, and Adib Farhadi, Building a New Afghanistan: The Value of Success, the Cost of Failure (New York: Center on International Cooperation, New York University in cooperation with CARE, March 2004)

24. Benjamin Duncan, “The Nation-Building the U.S. Neglects,” Al Jazeera.net (February 29, 2004)

25. “Security, Drugs, Funding Woes Hinder US Rebuilding in Afghanistan,” Agence France Presse (July 29, 2005)

26. Marcus Stern and Ahmad Shuja, “After Four Years and $4 Billion,” Copley News Service (December 23, 2005)

27. Margaret Coker and Anne Usher, “Four Years Later, Much U.S. Aid in Afghanistan Has Had Little Impact, Little is Done to Assure Quality of the Work, U.S. Report Says,” Austin-American Statesman (October 16, 2005)

28. See for example, Arthur Chrenkoff, “Coming Home. A Roundup of the Past Month’s Good News from Afghanistan,” The Wall Street Journal (July 11, 2005)

29. Paul Barker, “Why PRTs Aren’t the Answer,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting (November 3, 2004)

30. See Refugees International, “Security on the Cheap: PRTs in Afghanistan” (July 7, 2003) and also James Ingalls, “Buying Hearts & Minds in Afghanistan. U.S. Efforts to Maintain Imperial Credibility,” Z Magazine Online 16, 12 (December 2003)

31. “Afghanistan: Interview with Rural Development Minister,” Reuters (July 4, 2005) reprinted on Reuters Alternet

32. “Afghan Reconstruction Aid Bypasses Needy Villages,” Agence France Presse (January 30, 2006)

33. Mohammad Jawad Sharifzada and Shahabuddin Tarakhil, “Kabul’s Underbelly,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting (September 30, 2004)

34. “Kabul Choking on Air Pollution,” Peopleandplanet.et (June 9, 2004)

35. Rashid, “Cold Exposes,” op. cit.

36. Neamat Nojumi, “War – What is it good for? Remember Afghanistan?” Los Angeles Times (October 9, 2005)

37. A point made in Jim Ingalls, “Buying Hearts & Minds in Afghanistan. U.S. Efforts to Maintain Imperial Credibility,” Z Magazine Online 16, 12 (December 2003)

38. Andrew North, “Afghan Election Notebook 4 – Lonely Road,” BBC News (October 5, 2004)

39. Ben Arnoldy, “Afghans Left Out of Their Own Rebuilding,” Christian Science Monitor (May 24, 2005)

40. In Agence France Presse, “Afghan Aid ‘Wastage’ Under the Spotlight at London Conference” (January 29, 2006)

41. Neamat, op. cit.

42. “Afghan MP Says Billion in Air, but no Improvement,” Reuters (January 31, 2006)

43. Justin Huggler, “Afghan Candidate Calls for Expulsion of ‘Corrupt’ NGOs,” The Independent (September 13, 2005)

44. “Susanne Koelbi, “The Aid Swindle,” Der Spiegel (May 4, 2005)

45. Marc W. Herold, “An Island Named Kabul. Trickle-Up Economics and Westernization in Karzai’s Afghanistan,” Cursor.org (December 6, 2004)

46. In Agence France Presse, “Afghan Aid ‘Wastage’ Under the Spotlight at London Conference,” op.cit.

47. Farah Stockman, “Afghanistan: Few Haves and So Many Have-Nots,” The Boston Globe October 9, 2005)

48. “Afghan Aid ‘Wastage’,” op. cit.

49. Harry Dunphy, “Report: Most Afghan Aid Bypasses Government,” Associated Press (January 23, 2006)

50. Farangis Najibullah, “Eurasia Insight: Afghanistan: Nepotism, Cronyism Widespread in Government,” Eurasianet.org (May 11, 2003)

51. Rohde and Gall, op. cit.

52. “UNICEF: Afghanistan Child Mortality Soars,” Associated Press (August 5, 2005)

53. Ahmed Rashid, “Cold Exposes Afghanistan’s Broken Promises,” BBC News (March 17, 2005)

54. See Katherine Viner, “Feminism as Imperialism. George Bush is Not the First Empire –Builder to Wage War in the Name of Women,” The Guardian (September 21, 2002)

55. Beautifully recounted in Anne Brodsky, With All Our Strength; The Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan

56. Sonali Kolhatker, “Afghan Women Continue to Fend for Themselves,” Foreign Policy in Focus (March 4, 2004)

58. Mariam Rawi, “Rule of the Rapists,” The Guardian (February 12, 2004)

59. Jill Colgan, “Afghanistan – Kabul Beauty School,” ABC.net.au (September 30, 2003)

60. “Afghan Lipstick Liberation,” BBC News (October 17, 2002)

61. See “The Afghan Victim Memorial Project.”

62. See my “The Value of a Dead Afghan Revealed and Relative,” Cursor.org (July 21, 2002) at

63. A point dramatically made in my essay, “An Island Named Kabul,” op. cit.

64. "Afghanistan: ILO to Tackle Unemployment,” IRINnews.org (December b6, 2004)

65. Mishra, op. cit.

66. McDougall, op. cit.

67. Griff Witte, “In Kabul, a Stark Gulf Between Wealthy Few and the Poor,” Washington Post (December 9, 2005)

68. Derived from International Monetary Fund, Islamic State of Afghanistan: Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix (Washington D.C.: IMF Country Report No. 05/34, February 2005): 32. Unlike other heavy importers like Singapore and Malaysia which also export a lot, Afghanistan imports consumer goods and exports very little.

69. Tanya Goudsouzian, “Money Talks in Afghanistan’s Scramble for Resources. Investors Face Tantalizing Offers from Dubious Characters,” The Daily Star (August 28, 2004)

70. Mishra, op. cit I have added the [imported].

71. Details and photos in RAWA, “Ministers and highest level authorities occupy land and demolish the homes of poor people in Kabul” (September 9, 2003)

72. Andrew Maykuth, “Facing Land Grab by Elite, Kabul’s Poor Turn to U.N.,” The Philadelphia Inquirer (September 20, 2003)

73. Pamela Constable, “Land Grab in Kabul Embarrasses Government. Mud Homes Razed to Make Room for Top Afghan Officials,” Washington Post (September 16, 2003)

74. Witte, op. cit.

75. “Brick Kiln Closures Put 18,600 Afghans Out of Work,” Asia Pulse (December 17, 2005)

76. Mohammad Jawad Sharifzada, “Imports Threaten Local Industries,” Institute for War & Peace Reporting no. 158 (January 2005)

77. Rubin, Hamizada, Stoddard (2005), op.cit.: 24

78. Ibid

79. David Mansfield, Pariah or Poverty? The Opium Ban in the Province of Nangarhar in 2004/05 Growing Season and Its Impact on Rural Livelihood Strategies (Jalalabad: The Project for Alternative Livelihoods in Eastern Afghanistan (PAL), Policy Brief No. 1, September 2005)