Pulling the rug out:

Pseudo-development in Karzai's Afghanistan

Afghanistan as an empty space, part two. See parts one, three and four.

by Marc W. Herold

Departments of Economics and Women's Studies

Whittemore School of Business & Economics

University of New Hampshire

POSTED MARCH 7, 2006 --

|

Welcome to the "new" Afghanistan, and please, ladies and gentlemen proceed up these golden stairways.

The forms taken by pseudo-development in Kabul are many and grotesque: construction of luxury hotels (photo above of elevator in the new Kabul City Center), shopping malls and ostentatious "corrupto-mansions,"1 grinding poverty amidst opulence, pervasive insecurity, lock-down and deserted streets at night, an opium and foreign monies-financed consumption boom, pervasive corruption, alcohol and prostitutes for the foreign clientele, and the long list of "Kabul's finest" - foreign ex-pats2, a bloated NGO-community, carpetbaggers and hangers-on of all stripes, money disbursers, neo-colonial administrators, opportunists, imported Chinese and Soviet Republic prostitutes, imported Thai masseuses in the Mustafa Hotel, bribed politicians and local power brokers, facilitators, beauticians (of the city planner or aesthetician types), members of the development establishment, do-gooders, mercenaries, fortune-hunters, enforcers, etc.3

In this section, I shall address six inter-related aspects of Kabul's pseudo-development: (1). Opulence amidst destitution; (2). The absence of genuine governance in a culture of impunity; (3). Corruption; (4). Life in the ex-pat community; (5). Evidence of decadence -- alcohol and prostitution in Karzai's Kabul; and (6) The climate of generalized insecurity. Naturally, no aggregate data exists on these matters and so I shall rely upon scattered first-hand reports that form a coherent whole.

A monument to Kabul's "culture of impunity": a new "corrupto-mansion" in Sherpur. More examples here and here. |

On November 8, 2006, destitute Afghanistan opened a five-star, $36.5 million luxury hotel with rooms starting at $275 a night -- five times the monthly salary of an average Afghan civil servant (the executive suites go for $400 a night). Karzai who has long had a penchant towards Western luxury hotels -- in the 1980s his favorite lair was in the lobby of the Holiday Inn in Islamabad where he was known by the Western press corps as the "Gucci guerrilla" who distributed C.I.A. monies to the anti-Soviet mujahideen fighters4 -- presided over the grand opening, noting that the hotel could set an example for the development of the rundown capital,

Let's begin developing Kabul keeping the Serena hotel as the center of it.5

At the Kabul Serena Hotel, November 8, 2006 (source: Reuters) |

Business is booming in the nearby glitzy shopping mall, the Kabul City Centre (see cover photo). Hassan Saidzada, the manager of a watch shop there sells Swiss watches to cabinet ministers, jihadi commanders and newly made Kabuli tycoons. He recently sold a Breitling watch for $4,000 to the chief executive of a mobile phone company.6 Farooq Shah, a salesperson in Suhrab Mobile, sells Apple iPods and giant flat-screen televisions to foreigners and the Kabul nouveau riches. Nearby, Baki Karasu from Turkey, 41, who opened his new Beko store in the fall of 2005, sells imported refrigerators, dishwashers and ovens, but few Afghans can afford such luxuries or have the electricity to run them.7

Outside, Malik Shah, a 26-year-old day laborer has been standing on the freezing winter pavement since dawn, hoping for a day job that might earn him $48, but none had come up. Another 40 men waited beside him, wrapped in woolen shawls.9 They are persona non-grata in the Kabul City Center with its escalators, heated stores, Play Stations, fashion boutiques, and cappuccino bar.

Poverty, joblessness and high prices force many people of Kabul to beggary. One can see beggar men, women and children in every corner of the city. (Jan.23, 2005) |

Every morning for the last two months, Abdul Hanan, has waited behind a fence at the entrance to Bagram Air Base, hoping to be selected for a day job. Every evening, the 30-year old father of six walked away empty-handed. He and about 350 other men waited, gazing imploringly at American guards hoping to be one of these admitted each day for the daily wage of about $4. 0 This is four times the amount Abdul makes hewing hand-made wooden snow shovels out of tree trunks in Kabul. Abdul, his wife and six children live on $1 a day, live in one room without electricity or running water in Kabul.10

Thousands of women and girls who weave world famous Afghan carpets are treated as unpaid slaves by their male relatives, according to rights activists, but the government does nothing to regulate the industry.11 They work in damp, dark home factories. Child carpet weavers are addicted to nicotine and opium given to them in order to be calm. Child labor is rampant in Afghanistan. Impoverished families rely upon the meager earnings children can collect.12 Amid, 14, Andress, 13, and Rosedeen, 15, below work as mechanics in an auto repair shop in Kabul.

|

Many Afghan families only see reconstruction money by begging for it directly.13 Every day, Haroun, a 12-year-old sells chewing gum in the traffic outside the U.S. occupation forces' compound in Kabul. So do his three brothers and sister, aged 8 to 13. Their mother Gul Shah, 35, tends to a small home in a rundown neighborhood with open sewers and petty crime. The main room is heated by a small stove fed with animal feces. She says,

Of course, I don't want them to be in the streets, especially if they miss school. But otherwise we will not have enough to eat...So many changes...but none of them have reached here.14

Malnutrition is an everyday reality. A U.S. State Department report published in July 2005, noted that Afghanistan has the highest level of malnutrition in the world at 70 percent.

A Kabul native studying in Peshawar described peacetime Kabul with its rich and poor:

In Sherpur, the super-rich are building mansions verging on palaces. Meanwhile, a much larger number of Afghan squatters live in squalor in the shells of former government buildings, including one that once housed the embassy for the old Soviet Union. Abdul Qayoom sits in the sun making wooden snow shovels. A cow moos, a rooster crows and a young child whimpers. Older children laugh as they play.

Abdul, who makes less than a dollar day, and his family share space in one of three abandoned government buildings clustered behind a fence. The Spartan complex is home to some 700 Afghan refugees who returned after the Taliban regime fell four years ago.

They were drawn back to Kabul by promises of homes and jobs, said Abdul. But the government abandoned them as well as the buildings, he said. "We are disappointed," he added. Abdul's house is a small mud-brick shanty without electricity that he shares with his family of eight. The building around the shanties is nothing but a concrete shell.

Abdul's children, wearing tattered clothes, play around him as he tells his story: He fled his native province of Samangan in the north when the civil war broke out in 1992. He migrated to several provinces before ending up in Kabul after the fall of the Taliban in 2001."We came here in the hopes of a better life," he said. "But you can see how we live." Abdul and other returnees are scattered across Kabul in tents and houses made of tin, wood planks or mud. It has been three years since the government "dumped" them in abandoned buildings, as they say, promising aid and suitable shelter. They received two sacks of flour and a canister of cooking oil six months ago, Abdul said. "The government just makes promises but doesn't fulfill them," he added.15

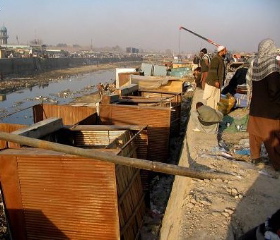

As the glittering new palaces of consumption were opening up in Kabul, another story was unfolding. In December 2006, the Kabul police authorities were destroying and removing small shops of poor families in the Pol-e-Bagh Amoni area near the Serena Hotel. The authorities wanted to have the area cleared so as to allow safer access by roads, since the Serena is where visiting dignitaries frequently stay. Karzai's police moved in and smashed small shopping stalls, dumping them into the Kabul River.

More photos at Pajhwok Afghan News

The peoples' livelihoods were destroyed without the slightest consideration for their future -- much like the destruction of poppy fields. The small shop owners protested and a confrontation with the city police ensued.

BBC Persia photo courtesy of RAWA |

Open sewers run through Kabul's streets. One of the movers of the Kabul Beauty School, Rosemary Stark recounts,

I fell into the sewer. Kabul is a huge city without a functioning sewer system. Imagine a gully between the sidewalk and the street that is 12 inches wide and up to two feet deep. Through it runs raw sewage, street garbage and this time of year, melted snow. Occasionally, there's a chunk of concrete thrown over it, but most of the time you have to leap to avoid it.16

Most residents in Kabul unable to afford diesel generators and buy fuel have no more than five hours' power every other night. A one-kilowatt generator costs at least $80 and diesel fuel goes for about $4 per gallon. As winter temperatures plunge below zero, family members huddle around wood stores and fires trying to stay warm. Cold-related illnesses are rampant. The unlucky ones die from the cold. Sahib Jamal, 60, says two already died this winter. At night she warms her calloused, blackened hands and her eight children on a fire. During the day, her eight children scavenge in the streets of Kabul for empty soda cans -- 60 cans bring in 40 cents. She said, "that's enough to buy three pieces of bread." A street boy, Cho Cha, instead of going to school washes cars to support his family, observing,

Life hasn't changed...I earn more money now than I did under the Taliban, but things are more expensive.17

But, the U.S.-backed Karzai routinely trots out new promises of a bright future. On a recent trip to Herat, Karzai was approached by an old man who told him, "only make promises you can fulfill."18 Wadir Safi, a law professor at Kabul University, says, "People have become fed up with promises and not seeing much improvement practically." Mohammad Reza returned with his family from exile in Iran by bus in late 2001, but now he's trying to go back. He says, "I wish I hadn't come. I had a better life there."

After three years of promises, Karzai finally increased the pay of Afghan civil servants and teachers by 40 percent, but this translated into taking the average salary to just over $40 to $50 a month, one-half the price of a one-kilowatt diesel generator. The country's 280,000 civil servants earn an average monthly wage of $50, while about 50,000 Afghans work for "aid organizations" where support staff earns up to $1,000 a month. The rest is foreordained: the qualified Afghans get hired away. The result is that Kabul in particular is brimming with a very small coterie of expensive foreign contractors, consultants and staff.19

A child living inside the old Kabul National Theater building in August 2004 |

As a result of the influx of ex-pats and all the other "fine people" in Kabul, inflation has taken hold and rents have skyrocketed. Rent for a three-room mud home is at least $200 a month -- four times the monthly salary of a civil servant! Just between September 2001 and January 2002, for example, the rent of Save the Children's Kabul office rose from $500 a month to $6,000 a month! In the dilapidated district called Daimazang, impoverished families live in 10-foot-square spaces partitioned off with mud brick walls on all sides. Some have strung plastic tarps for protection from snow and rain, while others simply face the sky. There is no electricity and little firewood; the price of wood had doubled to about $1 for twelve pounds. Hazrat Gul, 45, who makes $4 a day breaking stones for construction in the mountains around Kabul said,

We just have a blanket. During the night, we get under the blanket and we try to sleep.20

Mohammad Agha, a father of five who works as a bicycle mechanic, said he feared many in Daimazang would not make it through the winter. Agha, his own voice hoarse with pneumonia added, "all of the children are suffering. They are all coughing from pneumonia."

U.S. bombs, the opening of a parliament, and fraud-ridden presidential elections have not changed their everyday reality. Karzai's vision of developing Kabul along the lines of the opulent Serena Hotel manifestly has no place for poor people like Mohammad Agha.

The "new" Afghanistan has visibly benefited a few. Farah Stockman provided a nice description of their reality,

The fields of the few landowners who have received irrigation assistance have blossomed into squares of emerald green on a horizon of parched earth, while the Land Rovers of foreigners and Afghans with UN jobs or U.S. defense contracts dominate Kabul's traffic jams.

Commercial buildings, some financed by drug barons and others by businessmen returned from exile, feature never-before-seen wonders: Afghanistan's first escalator and modern shopping mall, complete with a metal detector at the door; a café that would not look out of place in Paris; and showrooms full of flat-screen televisions, Beverly Hills Polo Club watches, and Turkish suits that almost no one here can afford.

But for most residents, Kabul is still a city of antique rugs, open sewers, and mud houses built into the hillsides... Larger-than-life billboards left over from the recent parliamentary election show female candidates, now free to participate in politics. They gaze down on burka-clad women begging for money below. A short distance outside the capital, the signs of progress fade. The road east winds past a vast no man's land dotted by adobe villages that have seen little change in the past four years. Farther still, past Jalalabad, the road comes to a place of dilapidated Russian tanks on the horizon and a ruined ancient fort. There are no schools here. The only hint of the central government's influence is anger by local farmers over an effort to eradicate the growing of opium poppies.21

Islands of opulence amidst a sea of poverty and, let me repeat, "the only sign of the central government's influence is anger by local farmers."

A pillar of the façade of development and progress in Karzai's "new" Afghanistan is the establishment of governance to which I now turn.22 Even liberal analysts routinely trot out the idea that since 2003,

"...the Karzai government has been able to extend its authority to most areas of the country and to curtail the overbearing influence of warlords in national politics. The de facto veto that prominent warlords seemingly held over national policy from 2001-03 has largely been removed."23

This assertion remains questionable. What we do know is that those regional warlords are now ensconced in the Kabul government, that the Kabul government is largely a façade for U.S. influence and priorities, and that heightened insecurity pervades even Kabul.

As many have noted, the writ of the Kabul regime still barely extends to the periphery of the city during daytime with occasional forays outward into the provinces by heavily armed contingents of Afghan and U.S. occupation forces. The real governance, however, lies elsewhere as Amy Waldman cogently noted in 2004, dateline Kabul:

KABUL, Afghanistan -- "So what are we doing today?" Afghanistan's president, Hamid Karzai, asked the United States ambassador, Zalmay M. Khalilzad, as they sat in Mr. Karzai's office. Mr. Khalilzad patiently explained that they would attend a ceremony to kick off the "greening" of Kabul -- the planting and seeding of 850,000 trees -- in honor of the Afghan New Year. Mr. Karzai said he would speak off-the-cuff. Mr. Khalilzad, sounding more mentor than diplomat, approved: "It's good you don't have a text," he told Mr. Karzai. "You tend to do better." The genial Mr. Karzai may be Afghanistan's president, but the affable, ambitious Mr. Khalilzad often seems more like its chief executive. With his command of both details and American largesse, the Afghan-born envoy has created an alternate seat of power since his arrival on Thanksgiving. As he shuttles between the American Embassy and the presidential palace, where Americans guard Mr. Karzai, one place seems an extension of the other.24

And so on March 21, 2004, as part of Kabul Greening Week, Karzai trotted outside to plant a tree under the keen eye of Ambassador Khalilzad, a photo op duly recorded by the obedient Western press. The trees were planted and the ambassador and Karzai then met with United Nations personnel about elections, "a process that Khalilzad is ferociously prodding for."25

Some two years later in January 2006, Karzai issued a decree in Kabul ordering all concrete security barriers strategically placed in the capital to protect embassies and other such spots to be removed after torrents of complaints from inconvenienced drivers. But foreign organizations and the U.S. Embassy emphatically opposed the removal. The concrete blocs remain in place six weeks after Karzai's ultimatum. As Habibullah, 28, of Kabul observed,

Karzai's decrees don't have any authority even over Afghans -- how can we expect them to have an impact over foreigners?26

The spectacle of "governance" is illustrated by the recent elections in Afghanistan. Once again, a hollow fetish is made of the completion in October 2005 of the three steps outlined in the 2001 Bonn Agreement: the indirect election of a more representative government; the passage of a new constitution; and the holding of presidential and parliamentary elections.27

The Western governments, the United Nations, and mainstream press fell over themselves heralding the good news, a new president chosen in the country's "first democratic elections."28 Such assertions reflect a convenient historical amnesia: in 1986 and 1987, Afghanistan's first true national elections were carried out under Soviet military occupation, First, the KGB organized a 'loyal jirga' -- national assembly - in 1985 and through bribes and intimidation, got its new Afghan asset, Najibullah, positioned to take the place of the ineffectual Soviet puppet in office.29 Second, elections in 1986 and 1987 confirmed Moscow's choice. The resemblance with the U.S.-sponsored and manipulated, U.N-funded elections of October 2004 where Washington's choice was ratified, are all too obvious. In the U.S-U.N-run election, dangerous opposition candidates who did not recognize the legitimacy of the Karzai regime were excluded (by, for example, not guaranteeing their safety), warlords were bribed to give at least tacit support to Karzai, and diverse ethnic minority groups were allowed to participate thereby guaranteeing a fractured outcome. Moreover, Karzai was virtually the only candidate with the necessary transportation and security resources to mount a nationwide campaign. As Michael Scheuer cautioned, however, few of those who disagree with Karzai have put away their weapons and decided to wait peaceably for the next election.30

Predictably, little changed outside Kabul, where the country remains ruled by local warlords, "rented" power brokers, drug kingpins, and the Taliban. The old warlords have not been sent into retirement, but merely shuffled around among top provincial jobs or cabinet posts. Kandahar's infamous Gul Agha Sherzai -- once labeled "the U.N.'s warlord of the year" was removed from Kandahar, given a ministerial post, and then sent off to be governor of Nangarhar province.31 Ismael Khan and Rashid Dostum were brought in from their regional fiefs to take a place in the Karzai cabinet, whereas other local kingmakers and U.S. favorites such as Hazrat Ali (Nangarhar) and Mohammad Atta (Mazar) continue with "business as usual" in their regional empires. Mohammad Yusuf Pashtun was transferred from being Minister of Urban Development to the post of governor of Kandahar, but the real power in Kandahar is Wali Ahmad Karzai, the president's drug-trafficking younger brother.

A year later, another electoral spectacle was again on display to the world. The U.N.-funded parliamentary elections led to (the intended) weak, fractured body, due partly to U.S insistence that candidates stand as independents, not associated with any party. The International Crisis Group described the unusual election as a 'lottery.'32 The structure of the political framework was chosen so as to precisely guarantee continued executive power by the U.S-backed Karzai and his coterie of ministers. As expected, former militia bosses, war criminals and the like secured seats in the new parliament. In many parts of the country, old tribal politics still hold sway and old faces still dominate.33 Intimidation was rampant and according to even the New York Times, "whole districts have come under suspicion for ballot box stuffing and proxy voting."34 The voter turnout was a mere 53 percent, and in Kabul, the most politicized city, it was only 35 percent, reflecting disillusionment with the electoral spectacles.35 As Declan Walsh put it,

it seemed bizarre -- Afghanistan was hosting a great party for democracy, yet it looked as though nobody had bothered to turn up...officials were pedaling hard to find comforting explanations.36

Many who had voted in 2004 did not vote in 2005 as nothing had improved for them as a result of the first election. These poor results elicited a lot of hand ringing in October from the Washington Beltway 'internationals' crowd -- the likes of the Afghanistan Working Group, the United States Institute of Peace, Human Rights Watch, Larry Sampler of the Institute for Defense Analysis, etc.37 Sampler, formerly at UNAMA in Kabul, floated the specter that the international community could be "losing the hearts and minds" of the Afghan people as warlords appeared to be winning at the polls.38 They predictably won. In a country with an 80 percent illiteracy rate and the absence of western-style campaigning, voters simply voted along ethnic, tribal, religious, or power-broker lines. The Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission asserted that more than 80 percent of the winning candidates in the provinces and 60 percent in Kabul maintained ties to armed groups.39 The incoherence of post-election governance is underscored by others, saying the country has,

ended up with three or four governments...and now, the fifth, the parliament....described as a hodgepodge of conflicting ideologies and interests.40

But predictably, the U.S. Government and the mainstream U.S. press proclaimed with great fanfare that the parliamentary elections were proof that democracy had taken hold in Afghanistan, one U.S observer hailing a "miracle" had just occurred in Afghanistan. An exchange between that U.S. election observer and R.A.W.A. highlights the radically different interpretations.41 The representative of R.A.W.A. listed numerous individual cases of intimidation and fraud.

After some $350 million spent -- about one-third the value of all reconstruction projects completed in four years -- by the U.N. on the two elections, little tangible change has occurred for the vast majority of Afghans. Little of the reform agenda has taken root, while warlordism, corruption, drug trafficking, opulence in a sea of mass poverty, and a resolute Taliban insurgency grind on.

All the while, the human rights of ordinary Afghans continue to be abused. The independent Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) set up in December 2001, has documented these. In February 2006, scores of residents of the Sancharak district of the northern Sar-i-Pul province accused a number of former local commanders from the Northern Alliance parties -- the Jamiat and Junbish -- of running private cells, extortion and torturing people.42 The AIHRC confirmed the existence of private jails in the province; however the provincial governor denied the claims. The grandiosely titled Afghan Security Force -- former mujahideen hired by the U.S. forces to guard their bases -- is accused by local people of lawlessness and extortion.43

Little doubt remains that a culture of impunity reigns at all levels of governance in Afghanistan.

For average persons in the country's civil service, the Karzai regime doled out a $7-a-month wage increase in October 2005, which was met with despair and derision.44

Governance by the Kabul-based Karzai regime is a cruel hoax for most. For many, the biggest change from the Taliban era has been increased insecurity and stifling corruption.45 But the president continues on his heavy schedule of international junkets -- giving speeches, attending international conferences (at the World Economic Summit in Davos), accepting medals and other honors, and even returning to his old lair in Islamabad in February 2006:

Hamid Karzai in Islamabad in February 2006 (photo by Farooq Naeem, AFP) |

Appointments to key decision-making positions throughout the Afghan government have often been based upon nepotism and cronyism (as well as opportunism in the sense of bringing in possible powerful independents)46. Such nepotism and patronage extends to relatives of ministers part and present like Marshall Mohammad Fahim, Abdullah Abdullah, Yunos Qanooni, etc. In 2003, Minister Farhang admitted that" nepotism and cronyism have been increasing in Afghanistan." Favorite positions accorded are ambassadorships. Karzai himself chose two of his uncles, Abdul Aziz and Abdul Ghaffor, as ambassadors to the Czech Republic and Egypt. Reasons cited for such practices include considerations of trust, paying back supporters, and lack of jobs and few other sources of reliable income.

Moreover, at numerous times the Karzai regime has either tolerated blatant fraud (e.g., the bulldozing of homes in Sherpur47) or made executive decisions to pardon officials accused of corruption. The UN's special envoy on housing rights specifically named Marshall Fahim and Education Minister Yunus Qanooni as benefiting from the evictions.48 In 2006, Karzai issued a decree pardoning six officials convicted in the hajj ceremony corruption case.49 Some months earlier, an Afghan army general helped the kidnapper of the Italian NGO worker, Clementia Cantoni, escape from jail.50 A senior official of the central bank, Da Afghanistan Bank, went underground after fraudulently withdrawing sums from the bank in July 2005.51

Everyone in Kabul knows that to secure business deals requires paying a "commission." Bribery, corruption and extortion exist among the police, judicial system, public utilities, and even the national airline.52 No big business can start in Kabul without a percentage being paid to one or several ministers, generals, governors, and commanders.53 As Goudsouzian put it, "money talks in Afghanistan's scramble for reconstruction." An Afghan-American political analyst provided additional specifics,

The shadow economy...has given governors and commanders a kind of 'purse power' that once was the monopoly of the central government...a number of illicit income sources, such as opium, lumber, fuel and other smuggling items are in the hands of high government officials and commanders. In addition, custom revenues, which has always been the main source of national income for the Afghan state, has been largely taken by the governors/warlords and spent at their discretion rather than being controlled by the central treasury.54

The illegal businesses of provincial strongmen are overlooked in Kabul in return for political and military cooperation -- the famed renting of an Afghan. One of the more astonishing cases involves Hamid Karzai's younger brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, who blends the tribal, money power, and a role in "new" Afghan politics (as a candidate for parliament in Kandahar). Wali lives in a marble-clad mansion in Kandahar behind security walls that are more elaborate than even the local U.N. bunker.55 In 2004, reports began surfacing that Wali was involved in the drug trade.56 A year later, Wali who helped finance Karazai's presidential campaign, was directly implicated by the former interior minister, Taj Mohammad Wardak,

There is no direct proof but everyone knows. If you ask the people in the bazaar, four out of ten will tell you that Karzai's brother is exporting drugs.57

In a report published in January 2006 on Afghanistan's drug trade, Newsweek reported,

[Wali] was alleged to be a major figure by nearly every source who described the Afghan network to NEWSWEEK for this story, including past and present government officials several minor drug traffickers. 'He is the unofficial regional governor of southern Afghanistan and leads the whole trafficking structure,' says the veteran Interior Ministry official. Ahmed Wali Karzai vehemently denies the allegation...58

In mid-2005, Scott Baldauf wrote in The Christian Science Monitor about "the involvement of local as well as high-level government officials in the opium trade is frustrating efforts to eradicate poppy fields."59 In February 2006, none other than Habibullah Qaderi, Afghanistan's anti-narcotics minister admitted that some cabinet ministers were deeply implicated in the drug trade.60 The minister explained that this reality helps understand why trafficking is conducted with apparent immunity. Ali Ahmad Jalili, who resigned as Afghanistan's interior minister in 2005, even said,

sometimes, government officials allow their own cars to be used for a fee. Sometimes they give protection to traffickers. In Afghanistan, corruption is a low-risk enterprise in a high-risk environment. Because of lack of investigative capacity it is very difficult to get evidence. You always end up arresting the foot soldiers.61

One observer in the Mazar region noted when five local government officials in the Chamtal district of Balkh were dismissed in late 2005, "it's a case of the sharks arresting the small fish." Major high-level traffickers include favorite U.S. warlord, Hazrat Ail in Nangarhar and General Mohammed Daoud, a former warlord who moved on to become Afghanistan's deputy interior minister in charge of the anti-drug effort.62

Abdul Karim Brahowie, Afghanistan's minister of tribal and frontier affairs in 2005, said the government had become so full of drug smugglers that cabinet meetings had become a farce: "Sometimes the people who complain the loudest about theft are thieves themselves."63 A British official added that corruption was also rampant in the new National Assembly. Should one be surprised that Afghans greeted the Karzai government's newly launched anti-corruption drive with skepticism?64 A senior police commander in Kabul reported in 2005, "whatever number of police cars there are in Kabul, I can tell you that more than 50 percent of them are carrying drugs inside from one place to another."65

A German investigative journalist writing for Der Spiegel, concluded based upon experience in the northern province of Badakshan, that once the Taliban was deposed, "peace in Afghanistan [was] a boon for drug lords."66 Victory over the Taliban spelled defeat in the war on drugs.

I have demonstrated that the Afghan economy is fuelled primarily by foreign funds and by the opium economy -- it does not matter that this economy is illegal for when money earned is spent it sets in motion the Keynesian multiplier. Let me now turn to the life and style of ex-pat community and other members of "Kabul's finest."

I rely here upon the accounts by the ex-pats themselves. Daily life in the ex-pat community is discussed in the glossy, full-color monthly magazine, Afghan Scene, published since June 2004, by Domenic Medley, 33, a Britisher and former BBC journalist67. A member of the bloated ex-pat community reflected on a blog in June 2005 as follows:

We drive around in 4x4s, white, driven by Afghan drivers. We are served dinner. We live in compounds, cut off from the rest of Afghan life. We have, essentially, servants. Let me repeat that, for it bears emphasis: we have servants. We are paid enough per month to feed the average family for a year. In Kabul for one whole day, boys aged 10 years old pull a barrow around making a profit of 50 afs. We barely notice the odd dollar as we throw down tips in the restaurant, as my Ustad pointed out to me. If I were an Afghan, I would hate me: in fact I do. OK, so none of this really matters if we are doing good work. Let's pose the question: are we doing good work? Actually, let's not, because I don't like the answer I feel inclined to give. My colleague posed the question, and gave two answers, with two consequences. Either we are hated, in which case we need to get the hell out, right now, OR we are not hated. If the latter, we need to think about security very seriously. Now that Clementina is no longer in the hands of those who kidnapped her, I can speak of this without being accused of bad taste. If we are not actually hated, then living the way we do is simply more likely to institute that sort of hatred. We are insulating ourselves from a community which prizes community and belonging, which cements qawm ("us and them") as a concept, which prizes elaborate greetings, the protocols of civil behaviour. We consistently reject this, driving around in our big cars unsmiling and oblivious. This behaviour is not likely to endear us. Our security regulations demand that we remain in glorious isolation, but are themselves counter-productive in that they make the ordinary Afghan less likely to help us in times of need. We may only be threatened by a minority, but we are systematically alienating the good wishes of the majority. It is difficult to know what to do. Should we relax security and make an effort to exist in the community? Perhaps for long-stay people this makes most sense. The problem is that most of the staff here come and go, live in the ex-pat Kabul bubble, never learn the language, and never really interact with Afghans (I do not absolve myself from these accusations). Our ignorance and lack of commitment means we cannot safely live in Afghanistan-proper. Our work suffers fatally as a result.

The writer is obviously a member of a well-heeled non-governmental organization such as the agencies of the United Nations and countless other "aid" agencies in Kabul. The foreign NGO workers -- though not the Afghans -- earn on average $4,000 a month, mostly tax-free, and seldom spend it in local shops. Sure, they frequent the new Sony Centre and the Kabul City Centre, but most other shopkeepers only glimpse them as they drive around in one of the couple hundred $60-75,000 Toyota Land Cruisers, a majority owned by the U.N.68 A correspondent for the magazine Private Eye provides additional insight into life in the ex-pat community of Kabul:

The cruisers ferry them from office to restaurant to guesthouse. Some of them are quite lavish. A French organization has hired a four-star chef and Kabul's 'first boutique hotel' has opened for business...There's the swimming pool at the central U.N. compound and regular parties and barbecues. Memories of a party held by the DHL courier group last November [2003], when an opium pipe was passed around by UN staff, are still fresh. If boredom strikes, aid workers might also sign up for Tai Chi and Argentinean tango lessons. Booze, pork chops, prosciutto, marinated steaks, shrimps, cigars and caviar are regularly flown into the two PXs catering for westerners. Run by westerners themselves, none of their vast profit reaches the local economy. Now the German brewer of Biltburger Pils has a representative in Kabul signing up new customers. And Starbucks is here too 'for office and home delivery.' Again none of this investment is much to us locals. True, a few Afghans are 'lucky' enough to get jobs cleaning, serving tea or gardening...69

The letter elicited an indignant rebuke where the writer (country director of the population-control N.G.O., PSI International) pointed out that NGO staff travel around in $33,000 Nissan Patrols and that an annual salary of $48,000 in Kabul is hardly inflated given the "pretty harsh conditions" of life in Kabul.

And one wonders, along with the government's former planning minister, Ramazan Bashardost, why so little of the reconstruction aid committed actually translates into tangible life-improving things?

A professor of film at Boston University, John Robert Kelly, published an account, "Beer and Loafing in Afghanistan," in the right-wing blog InstaPundit (run by University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds) about his experiences in Afghanistan as an ex-pat. I quote from it extensively here because it luridly captures important facets of some (not all) ex-pat thinking:

It's a lonely and frustrating life for the western NGO and UN grief relief workers in Afghanistan. There are those hefty paychecks, often amounting to thousands of dollars --tax-free-- a week, but no place to spend it. After all, how many carpets and antique swords can one collect? Then there's that pesky problem of the desultory hours surfing the net in air conditioned estates converted to office space, but nowhere else to travel, except back to the villa in new, chauffeured Landcruisers for an evening of the same old faces, same old conversations. Numerous fearful directives and warnings keep these NGO workers from hitting the street and meeting and mingling with the Afghan population. When these warnings are lifted, few wish to wander from their guarded compound. There's a very valid awareness that the NGO permanent party isn't well liked by the Kabulis. An elderly Hazara rug merchant whose business has been halved by the timidity of NGO shoppers, snorts derisively in perfect English, ""Their feet never touch the ground in Kabul."" And he's right. In a typical week, one sees just a few handfuls of westerners, mostly ISAF troops on holiday, even in the safest zones of the tourist traps and souvenir shops on Chicken Street, Kabul's answer to Rodeo Drive. Many of the professional compassion corps are feeling restless and bored; they've already been staff in Kosovo, East Timor and Afghanistan, and nowadays believe they belong in Iraq, that's where the real money is. In the status conscious pecking order of NGO hierarchies, Afghanistan is passe. Only the palpable danger of Iraq keeps down the flurry of resumes from Kabul to Baghdad. It's the rare NGO worker who applies for work before the shooting is over and the maximum salaries are fixed. The money has been spent in Afghanistan, the bank is closed. The UN has larded tens of millions of dollars on an enormous fleet of brand new top-of-the-line Toyota Landcruisers, many times that on inflated salaries, mansions and the luxurious perks of occupying pashas. The needy locals are not amused. The American citizens who've liberally financed this largesse would be appalled at the waste. It's not all monotonous or pointless in Kabul; at one French NGO housed in a stunning antique-laden chalet, I've devoured a seven-course meal prepared by a 4 star chef. Then there's always the sumptuous UN House, where one can take a dip, mingle poolside among scandalous bikinis and dowse dehydration with inspired cocktails fashioned by our languid Euro masters. Unfortunately, since "American UN employee" is an oxymoron, our one attempt to storm the formidable barricades is a spectacular failure. We're rudely turned away, despite flashing $20 bills to the Afghan UN security. My companion, a fierce Pushtoon-American licensed to pack a very visible Glock 19, glances back at the sunbathers as we're escorted out: "We've paid for all this with our taxes, you bastards!" One of the Pushto guard's shrugs his shoulders sympathetically, muttering an apology that suggests "someday this will all be ours again." For all the heroic American efforts in Afghanistan, truly and deeply appreciated by the indigenous population, we're still treated as unwanted nuisances by the predominantly European NGO residents.

For us hoi polloi, there was always the Irish Pub that opened on Saint Paddy's day to such fanfare in the western press--and with far greater gratitude in Kabul--but is now shuttered, a victim of its own success.

Sean McQuade's commercial instinct was impeccable: the creation of a stimulating oasis for thirsty westerners in one of the driest and most oppressively conservative cities in the Islamic world. The demand was high--a bit too high, according to some Afghans. In a city where getting stoned isn't an amusing colloquialism for intoxication but a literal description for the Taliban sport of getting smashed at the soccer stadium, Sean's otherwise laudable enterprise had a few defects in the business model, the most notable was that his public house had a mullah next door. McQuade had hoped for a lower profile for his tavern, but the spirited swarms of tipsy patrons pouring into their NGO SUVs in the late hours scandalized the neighborhood and not even the owner's gracious offer of baksheesh to rebuild local roads and schools could keep the speakeasy alive. All is not lost for parched westerners in search of a public lager with good company, however, since other more discreet taps have opened throughout the city. At the Mustafa Hotel, long the favorite haven of adventuresome tourists and savvy international journalists, where last summer we diluted toxic contraband Tajik vodka (at $50 a liter) with Fanta, one can not only legally quaff a draught, but also surf the net or file a story at the same time...and not a mullah for a hundred meters.70

Further entertainment for the well-heeled bored ex-pats and nouveau riche Afghans is provided with the reopening of the Kabul golf course, the city's first 'gastroclub'-cocktail bar (the Elbow Room), listening to Saad Mohseni's commercial radio (Arman FM) and television (Tolo TV) stations, or simply perusing the latest Afghan Scene magazine -- whose first issue featured a fashion piece entitled "I can't believe I'm buying a tube top in Kabul."71 The Bloomberg news agency featured an article titled "Whiskey Shots Replace Gunshots in Rebuilding, Revitalized Kabul."72 It described the scene close to midnight at the Coco Cabana club in the Wazir Akbar Khan neighborhood where whiskey shots were still being noisily exchanged, adding,

This is a new Kabul, a rebuilding city full of high-rises put up by the nouveau riche modeled on gaudy Pakistani buildings they remember from their exile. With their black-and-white marble trim, fussy columns and multicolored glass facades, they stand like arrogant peacocks over their humble adobe neighbors. Paid handsomely for working in a war-ravaged country, the burgeoning ex-pat community rebuilding the country flocks to trendy international restaurants like L'Atmosphere, owned by a Frenchman who originally came to Kabul to train Afghan journalists. Here, behind high steel walls, a passageway meant to mimic a Provencal farmhouse gives way to a well-kept garden, complete with a swimming pool. Bikini-clad French women exchange greeting kisses on the cheek as Bridgette Bardot-era music pumps gently from well- hidden speakers. Tables fill up quickly with hungry U.N. workers and diplomatic staff who pore over the menu, looking for the best Beaujolais.

Any guest staying overnight at the Serena Hotel would find familiar luxury, as,

...almost everything that the luxury hotel requires -- from European cheeses for its breakfast buffet to chemicals for the laundering of its downy white towels to the Penhaligon lotions and shampoos with which the bathrooms are lavishly stocked -- must be imported. Goods are flown from Dubai into one of Pakistan's international airports, then taken by railroad to the border city of Peshawar, where they begin a 10-hour journey by truck over the Khyber Pass to Kabul.73

Ghulam Hazrat Safi returned from Dubai and invested $35 million building the green glass, 10-story Kabul City Center shopping mall and the adjoining Safi Landmark Hotel. The mall opened in September 2005. Since then,

...groups of young Afghan men and women have been enjoying shopping in stores that sell perfume and scented candles, or gossiping over coffee in the basement cafe. Wearing jeans under a long black robe, Marsila, a 25-year-old student studying English literature at Kabul University, said she and her classmates have become mall rats.74

Interior of the Kabul City Center |

More photos at Pajhwok Afghan News

Civilization restored (and imported).

Amongst "Kabul's finest" figure the freelance soldiers of fortune (e.g., ex-Green Beret Jack Idema), carpetbaggers of all stripes, enforcers (e.g., DynCorps, Bearing Point, etc). They apparently hang out at Kabul's Mustafa Hotel,

...muscles and automatic weaponry on display, guzzling beer and flirting with the giggling Thai girls flown in to staff the hotel's new massage parlour and beauty salon. The American ex-soldiers who have flocked to Afghanistan tend to be men of mystery, their ranks dominated by laconic Southerners. They are to be found in the Irish bar of the Mustafa, a former secret police detention centre hurriedly converted into a hotel after the fall of the Taliban and now run by an Afghan-American car dealer from New Jersey. Over expensive glasses of Jack Daniel's, they swap hair-raising tales, compare weaponry and joke with the massage parlour girls who dress in camouflage waistcoats.75

Fortune-hunter, Jack Idema, went a bit beyond even the standards of Kabul's chaotic violence, by operating a private jail where he and his thugs hung prisoners upside down, tortured them, etc. But in reality, the most exciting it gets for most of these macho men is guarding western businesses for several hundred dollars a day.

Civilization protected.

As part of the massive influx of foreigners and newly rich westernized Afghans, alcohol consumption and prostitution have made a strong comeback. The compromise reached regarding alcohol was that only foreigners are officially allowed to consume liquor even though the Afghan constitution bans alcohol.76 Bars and clubs openly serve alcohol and when closed-down by authorities are quickly re-opened. Along the road between Kabul and Jalalabad, several stalls openly sell Heineken beer. One stall owner said to Kim Barker as a police officer walked by, "no problem...Foster's, Heineken, Beck's, whiskey vodka. I have wine for women too."

As usually happens, along with alcohol and private clubs, commercial sex has sprung up. In March 2005, the Disco Restaurant opened. The new club hung a banner along the sidewalk featuring a half-naked dancing couple. The Disco served no food but did provide four Chinese women willing to dance with foreign men. The owner, Zhaogia Guo says he wanted to make money and give foreign men a place to dance.

In early 2005, articles began appearing providing details on how Chinese restaurants and guesthouses in Kabul often served as fronts for popular brothels. Justin Huggler reports that "most are located in the expensive neighborhoods like Wazir Akbar Khan and Shar-e-Nau, amid the expensive restaurants and bars frequented by the plethora of foreign diplomats, UN staff and NGO workers who live in Kabul."77 The Silk Road Restaurant located just across from a girls' school, is one of the many new brothels opened up in Kabul.

(Source: Tom Pennington, Forth Worth Star Telegram/KRT, Dec. 30, 2005) |

Civilization's underside tasted by some.

Again, some facilities get closed down by authorities but then re-open under another name. In February 2006, Afghan police raided many restaurants, arresting 46 foreign women for selling alcohol to Afghans and engaging in prostitution.78

According to a regular brothel patron, prostitutes in Kabul are divided into two categories: Chinese and those from the former Soviet republics.79 Even the prostitutes are imported!

A Mr. Sabit who is legal adviser to the Interior Ministry makes the rounds of guesthouses, bars and clubs in Kabul. Kim Barker reported:

On one recent visit, he gestured at a Chinese woman dressed in a fur jacket, fishnet stockings, white miniskirt and white boots almost unbelievable in a country where many Afghan women still cover their faces and everything else. "Look at that," he muttered. The only customer was a Western man, sitting at a table by himself. Although Sabit would like all these places to disappear, he will probably end up disappointed.

The large foreign community in Kabul operates economically as an import-dependent bubble economy onto its own with few domestic linkages. At best, some crumbs of the incomes earned trickle-down to poorer segments of society. The organizations visibly function with very large overheads. Along with the arrival and growth of the ex-pat inevitably come certain western social ills.

Widespread agreement exists that in Kabul and larger Afghanistan a climate of fear and instability exists. A resurgent Taliban insurgency threatens vast swathes of the nation and even affects large cities like Kandahar, Kabul, and Mazar-i-Sharif. The year 2005 has been the bloodiest since 2001. The insurgency in the provinces has successfully disrupted reconstruction work, e.g., in the south some 200 schools are closed due to violence.80 The insurgency's new tactics -- suicide bombings, improvised explosive devices -- and kidnappings promise to further raise the general sense of insecurity.81 Kabul's thoroughfares are empty by 9 P.M. and the 'internationals' are advised to stay at home under curfew. A recently arrived employee of the United Nations Development Program writes,

This place is like Europe after WWII, except it is full of Afghans and they are not particularly industrious or organized. I am living in a guesthouse of UNDP staff and have settled into a routine, exercises at dawn, breakfast, work, lunch, work, a ride home, a drink, dinner, reading and bedtime... with some writing in between. There is no liberty permitted here, we go and come to the office and can't be on the streets at all. Security is tight. WE are picked up by a UN car and dropped off at 6:30 P.M.82

Afghan police officer Ghulam Raza, 26, frisks guests before they are allowed to enter a wedding at the Sham-e-Paris restaurant in Kabul, the capital. Such security practices were unknown in Afghanistan until recent months (Photo by Griff Witte, Washington Post) |

A report in a Canadian newspaper in early 2006 cautioned,

Kabul -- The city smells of dust, diesel, wood smoke, windborne curry, chai tea and a whiff of raw sewage -- but also fear. And it is growing...in the past 18 months, and even more so in the past six months...[the] mood of optimism has shifted to a grinding sense that things are slowly falling apart, expatriates here say. The evidence is everywhere on the streets. Guesthouses that once thrived with foreign business are dark and empty, and drivers willing to ferry foreigners are in short supply. The one hotel in Kabul that still does a robust trade, the Gandamak Lodge, is literally ringed by gates and razor wire and guarded by men with automatic weapons...many humanitarian workers from abroad have left...foreign embassies fly no flags and carry no displays that would overtly give their presence away...road travel from Kabul to...Kandahar...is now discouraged for anyone traveling without protection of an armed convoy.83

The situation is exacerbated by an entrenched, well-financed opium mafia threatening the role of law.

Within the Washington Beltway, officials claim that a measure of peace and security has finally taken root in Afghanistan. But as Wahidullah Amani wrote for the independent newspaper of the Institute for War & Peace Reporting,

...try telling that to Abdul Hadi, a resident of...Kandahar. Hadi had just recently witnessed a suicide bombing that left one dead and three injured, in addition to the bomber himself. Although the bomber may have been aiming to hit a passing convoy of United States-led Coalition troops, his victims were all Afghan civilians. In Kandahar, we are afraid of the trees, of the air, of the ground we walk on,' said Hadi as he gestured helplessly at his surroundings. 'This is no life'.84

A policeman in Kandahar added, "as a policeman, I go on duty in the morning never knowing whether I will live to go home in the evening."

The Karzai regime argues that its police and army forces are now in control of the country. Based upon what evidence? The absence of large-scale, pitched battles with large Taliban forces -- the Karzai spokesman saying, "the opposition is no longer able to fight face to face". What they don't say is that it is the destructive force of B-52Bs, the F-16s, the A-10s, and the Apache helicopters which are the explanation of the Taliban refraining from launching attacks with larger units and instead focusing upon small-scale targeted missions.

The situation in the provinces which were once strongholds of the Taliban is even more precarious for the United States and its Afghan client's forces. Griff Witte recently provided a vivid description of Uruzgan, the homeland of Mohammad Omar, When the United States sent tons of wheat seed here this winter [2005/6] to be given to farmers as an alternative to growing poppies, local officials sold the seeds and pocketed the money. When the U.S. ambassador came for a visit Jan. 5, a suicide bomber detonated himself several hundred yards away, killing 10 people. And every time U.S. troops have managed to seize a portion of Uruzgan province, this remote, ruggedly beautiful region of south-central Afghanistan, enemy fighters have simply slipped away and found new hiding places among its endless craggy hills and hollows.85

The United States, as part of controlling the empty space of Afghanistan at least cost, has been able to "persuade" the Dutch to oversee volatile Uruzgan Province, the Canadians to do the same in Kandahar, and the British to oversee volatile Helmand Province.

In nearby Pakistan, a thoroughly reorganized Taliban movement has even established the Islamic Republic of [North] Waziristan86. By taking control of almost all of the North Waziristan tribal area, the Taliban have gained a significant base from which to wage resistance against U.S.-led forces in Afghanistan.87

This section has woven together a tapestry of the grotesque pseudo-development whose related threads include: a culture of impunity and corruption, obscene opulence amidst grinding poverty and unemployment, a façade of governance marketed with a $300 million price-tag, and an import-driven, high-priced ex-pat economic bubble in Kabul. The whole looks like the chimera expressed by Karzai,

Let's begin developing Kabul keeping the Serena hotel as the center of it.88

Coming next, Part Three: Hat Trick: Selling Brand Karzai.

Footnotes

1. Naturally in the midst of this, a few organizations (and individuals) genuinely try and do succeed in making life better for the common people - for example, the hospital run by the Italian N.G.O., Emergency in Kabul comes to mind, the wonderful work on de-mining carried out by a number of NGO’s, the vaccination campaigns administered by the United Nations, the projects of Oxfam, BRAC and RAWA, etc.

2. Let me be very clearly, I am NOT saying all ex-pats. Some live modestly and even in some hardship. For an example, see Raul of the UNDP who describes his life in Kabul at “Raul in Kabul.”

3. Two years ago, I described this world in my “AfghaniScam: Livin’ Large inside Karzai’s Reconstruction Bubble,” Cursor.org (September 24, 2003).

5. Agence France Presses, “Destitute Afghanistan Opens its most Luxurious Hotel” (November 9, 2005). Four years ago, I laid out the essences of what I thought would be the Karzai approach to development and labeled it “The Intercontinental Model,” see “Karzai & Associates’ Trickle-Down Reconstruction,” Cursor.org (May 12, 2002). The Serena hotel was funded by the Aga Khan Foundation for Economic Development and the World Bank (through its International Finance Corporation).

6. Declan Walsh, “Kabul: Booming and Broke,” The Guardian (December 28, 2005).

7.Griff Witte, “In Kabul, a Stark Gulf Between Wealthy Few and the Poor,” Washington Post (December 9, 2005).

8. Walsh, op. cit.

9. Anita Powell, “Desperate Afghans Turning to U.S. Army for Work. Amid Staggering Unemployment, Day-Laborer Jobs Prized,” Stars and Stripes (February 23, 2006).

10. See and listen to video on Abdul at “Kabul’s Poor,” Copley News Service (no date).

11. “Afghan Carpet Weavers are Unpaid Slaves, Rights Activist,” Agence France Presse (December 1, 2005).

12. For a superb visual portrayal, see Chien-Min Chung, “Afghan Child Labor,” The Digital Journalist (2002).

13. The livelihood strategies of the urban poor in Kabul are examined in Pamela A. Hunte, Some Notes on the Livelihoods of the Urban Poor in Kabul, Afghanistan (Kabul: Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), Case Studies Series, February 2004).

14. Walsh, op. cit.

15. Ahmad Shuja, “Peacetime Kabul Has Its Rich and Poor,” Copley News Service January 21, 2006.

16. Rosemary Stasek, “Letter From Kabul,” Mountain View Voice (February 25, 2005).

17. Farah Stockman, “Afghanistan: Few Haves and So Many Have-Nots,” op. cit

18. Sayed Salahuddin, “Afghan Prosperity a Dream for Most, Frustration Grows,” Reuters (December 1, 2005).

19. The above comes from Toby Poston, “The Battle to Rebuild Afghanistan,” BBC News (February 26, 2006).

20. Witte, op. cit.

21. Stockman, op. cit.

22. An interesting analysis of governance or the lack thereof in Afghanistan is also presented in Mark Sedra and Peter Middlebrook, “Beyond Bonn. Revisioning the International Compact for Afghanistan,” Foreign Policy in Focus (November 2, 2005). The report is long on “things to be done” and rather short on “what is and why.”

23. Sedra and Middlebrook, op. cit.

24. Amy Waldman, “In Afghanistan, U.S. Envoy Sits in Seat of Power,” New York Times (April 17, 2004).

25. Waldman, op. cit.

26. Wahidullah Amani, “Barriers Prove Insurmountable for Karzai,” IWPR (February 18, 2006).

27. See comments by Barnett Rubin in Panel II: Politics, Democracy, and Institution Building (Washington D.C.: conference “Winning Afghanistan,” American Enterprise Institute, Washington D.C. (October 2005)).

28. See UNAMA statement and “The First Democratic Elections in Afghanistan: A Report by the Bipartisan Observer Team,” Foreign Press Center Briefing (October 15, 2004).

29. The analogy is from Eric Margolis, “Bogus Elections in Kabul.”

30. Michael Scheuer, “History Overtakes Optimism in Afghanistan,” Terrorism Focus (The Jamestown Foundation) 3, 6 (February 14, 2006).

31. Robert Fisk, “Ladies and gentlemen, let's have a big hand for Gul Agha - the UN's warlord of the year,” The Independent (August 9, 2002).

32. “Elections Will Create Weak and Divided Parliament, Says Expert,” AKI Italy (September 7, 2005).

33. Paul McGeough, “Old Ways Linger Beneath a Veil of Votes,” Sydney Morning Herald (September 10, 2005).

34. Carlotta Gall, “Voting Fraud is Found in Afghanistan’s Election,” New York Times (October 3, 2005).

35. “Despite Assurances, Karzai Falls Short on Reforms,” The Daily Star (Lebanon) (October 10, 2005).

36. Declan Walsh, “Democratic Disillusionment,” The Guardian (September 23, 2005).

37. For a description of the views see the summary of a conference held in October 2005 at the neo-conservative bastion, the American Enterprise Institute, “Winning Afghanistan.”

38. Larry Sampler, “Disappointment Grows in Democracy’s Dividends” Washington D.C.,: conference “Afghanistan: Old Problems, New Parliament, New Expectations,” United States Institute of Peace, October 2005).

39. Sedra and Middlebrook, op. cit.: 9

40. Jim Lobe, “Four Years into Afghan Campaign, Perils Abound,” Antiwar.com (October 6, 2005).

41. See Diane Tebelius, “The Afghanistan Miracle,” The Seattle Times (October 4, 2005) and Mehmooda Sheikiba, “The ‘Miracle’ or a Mockery of Afghanistan?”

42. Ahmad Naeem Qadiri, “Sar-i-Pul Residents Complain of Torture Cells,” Pahjwok Afghan News (February 15, 2006).

43.Kim Sengupta, “British Troops Fear Backlash as Afghans Attack Opium Crop,” The Independent (February 26, 2006).

44. “Despair at Afghanistan’s First Civil Service Wage Hike,” Agence France Presse (October 16, 2005).

45. Sedra and Middlebrook, op. cit.: 4

46. Farangis Najibullah, “Afghanistan: Nepotism, Cronyism Widespread in Government,” Eurasianet.org (May 11, 2003).

47. Details and names of close Karzai associates who benefited provided in RAWA reporter, “Crime and Barbarism in Shirpur by Afghan Ministers and High Authorities,” Rawa.org (September 16, 2003).

48. “Afghanistan’s Poor Losing Homes: UN Report,” CBC News (April 11, 2004).

49. “Karzai Pardons Officials Convicted in Hajj Corruption Case.”

50. “Army General Helped Kidnapper to Escape: Afghan Official,” Reuters (August 9, 2005).

51. Ahmad Nareem Qadri, “Financial Fraud Unearthed at Afghan Central Bank,” Pajhwok Afghan News (July 14, 2005).

52. For a description see Hafizullah Gardish, “Corruption Rampant at Every Level,” Afghan Recovery Project No. 120 (May 27, 2004).

53. Tanya Goudsouzian, “Money Talks in Afghanistan’s Scramble for Reconstruction,” The Daily Star (August 24, 2004).

54. Goudsouzian, op. cit

55. McGeough, op. cit.

56. Reported in Carlotta Gall, “Afghan Poppy Growing Reaches Record Level, U.N. Says,” New York Times (November 19, 2004).

57. Declan Walsh, “Karzai Victory Plants Seeds of Hope in Fight to Kick Afghan Opium Habit,” The Guardian (January 1, 2005).

58. Ron Moreau and Sami Yousafzai, “A Harvest of Treachery. Afghanistan’s Drug Trade is Threatening the Stability of a Nation America Went to Stabilize. What Can be Done?” Newsweek (January 9, 2006).

59. Scott Baldauf and Faye Bowers, “Afghanistan Riddled with Drugs,” The Christian Science Monitor (May 25, 2005).

60. Toby Harnden, “Drug Trade 'Reaches to Afghan Cabinet,’” Telegraph (February 5, 2006).

61. Harnden, op. cit

62. See Paul Watson, “Afghanistan: A Harvest of Despair. The Lure of Opium Wealth is a Potent Force in Afghanistan,” Los Angeles Times (May 29, 2005).

63. Baldauf and Bowers, op. cit.

64. "Afghans Greet Government’s Newly Launched Anti-Corruption Drive with Skepticism," Institute for War & Peace Reporting (February 4, 2006).

65. Baldauf and Bowers, op. cit.

66. Dirk Kurbjuweit, “Peace in Afghanistan is a Boon for Drug Lords,” Der Spiegel (August 17, 2005).

67. And available for perusal here.

68. Salesman Muhammed Khaled at the Toyota dealership said, “we have enough customers willing to pay US $50,000 for this car. Customers are either foreigners, important commanders or government officials” (“Capitalism Intensifies Class Divisions in Afghanistan,” Associated Press (September 28, 2003) reprinted in Taipei Times (September 28, 2003).

69. Correspondent for Private Eye, “Letter from Kabul,” Afghan Scene no. 2 (July/August 2004): 30-31.

71. Duncan Campbell, “Kabul Tunes into Capital Pursuits,” The Guardian (June 17, 2004).

72. Michael Luongo, “Whiskey Shots Replace Gunshots in Rebuilding, Revitalized Kabul,” Bloomberg.com (September 20, 2005).

73. Kayherine Zoepf, “Emerging Destination of the Year: Kabul,” The New York Times (January 22, 2006).

74. Laura J. Winter, “A Rising Kabul Rules,” New York Daily News (November 27, 2005).

75. Nick Meo, “Kabul’s Colonel Kurtz,” Sunday Herald (July 11, 2004).

76. Kim Barker, “Compromise on Alcohol Leaves Afghans Shaken, Stirred,” Chicago Tribune (April 25, 2005.

77. Justin Huggler, “Chinese Prostitutes Arrested in Kabul ‘Restaurant’ Raids,” The Independent (February 10, 2006).

78. Justin Huggler, op. cit.

79. Michaela Cancela-Kieffer, “Business Turns Bad for Chinese Brothels in Afghan Capital,” Agence France-Presse (February 4, 2005).

80. IRIN, “Afghanistan: Education Crisis in the South with 200 Schools Closed,” Reuters (February 8, 2006).

81. Kidnappings are primarily undertaken by gangs. In 2004, a gang kidnapped the cousin of the very wealthy Habib Gulzar, owner of Kabul’s only official Toyota dealership and a ransom was paid for his release.

83. Michel Den Tandt, “Afghans Fight Rising Fears,” The Globe and Mail (January 23, 2006).

84. Wahidullah Amani, “Growing Sense of Insecurity,” Institute of War & Peace Reporting (December 23, 2005).

85. Griff Witte, “Afghan Province’s Problems Underline Challenge for U.S. Resilient Insurgency, Corruption Keep Uruzgan a ‘Last Frontier,’” Washington Post (January 30, 2006).

86. Syed Saleem Shahzad, “Terrorism: Taliban Video Claims Mulsim State in [North] Waziristan,” Adnkronosinternacionmal (AKI) (February 6, 2006).

87. Syed Saleem Shahzad, “The Taliban’s Foothold in Pakistan,” Asia Times (February 8, 2006).

88. Agence France Presses, “Destitute Afghanistan Opens its most Luxurious Hotel” (November 9, 2005).