U.S. military strategy to maintain Afghanistan as an 'Empty Space'

Afghanistan as an Empty Space, part four. See parts one and two and three.

by Marc W. Herold

Departments of Economics and Women's Studies

Whittemore School of Business & Economics

University of New Hampshire

POSTED MARCH 18, 2006 --

After a couple of years of learning following the demise of the Taliban as a visible presence, the United States military has perfected its strategy of maintaining Afghanistan as an empty space at least cost. The strategy is comprised of six inter-related elements:

- 1) Relying upon two levels of 24/7 air power;

- 2) Concentrating hub activities at two large, permanent U.S. bases -- Bagram and Kandahar -- while NATO will operate a large new base under-construction in Herat capable of housing 10,000 troops.1 In 2005, the U.S. Air Force spent $83 million upgrading its two major bases in Afghanistan;

- 3) Maintaining some 30 smaller, forward operating bases with 14 smaller airfields housing highly mobile air and ground forces. U.S. forces stay in their fortified bases and only carry out special search operations, leaving routine patrolling to their local satrap forces;

- 4) Reducing its own ground forces commitment in order to cut both financial and political costs (e.g., dead and injured U.S. troops) and having N.A.T.O. forces (especially Canadian, British and Dutch) replace U.S. occupation forces in the most volatile regions -- Kandahar, Helmand, and Urzugan;

- 5) Employing local satrap forces of the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police to do routine patrolling and ground combat, but with heavy U.S. aerial tactical support (see #1 above). But, success here depends upon training of these army and police forces;

- 6) Increasing use of "strategic communication" (or disinformation) by the Bush Administration.

The Pentagon has deployed air power assets so as to effectively maintain a 24/7 presence over Afghanistan. High-flying large bombers -- B52Bs and B1-Bs based in Diego Garcia -- are constantly in the air high over Afghanistan, ready to provide tactical air support at short notice. In the past couple years, the Pentagon has relied more upon un-manned aerial vehicles of the Predator type. These drones patrol 24/7 over regions deemed to be in hostile hands (e.g., the northeastern and eastern provinces of Afghanistan especially in the border areas), launching rocket attacks upon targets.

At a lower-level, other tactical aircraft based within Afghanistan (and from U.S. carriers operating in the Arabian Sea -- especially the close air-support heavily armed A-10 Warthogs (at Bagram) and AH-64 Apache attack helicopters (at the two large U.S. bases as well as at many of the forward operating bases) -- provide more focused and more mobile fire power. The effect of such very mobile, massive aerial firepower has led the insurgents to change tactics away from concentrating their forces, focusing instead upon small-scale, quickly executed, highly pin-pointed attacks (e.g., police posts, government buildings, schools and other reconstruction projects, U.S. Humvee patrols, etc.). Attacks upon Afghan National Army and Police are intended to raise the cost of recruiting such local U.S. satraps. The tactic is hit-and-run, an adjustment to U.S. air power deployment and having nothing to do with the desperate tactics of an almost defeated enemy (as the Pentagon and the U.S. corporate media so loudly trumpet).

The tactic is to cause sufficient U.S. casualties that the issue remains visible politically. And certainly in 2005, the Taliban and their associates did just that. The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) reported that Afghanistan in 2005 was more dangerous for American troops per capita than Iraq:

According to USIP, in the spring of 2005 U.S. troop casualties -- both injured and killed -- reached 1.6 per 1,000 soldiers in Afghanistan, compared with a casualty rate of 0.9 in Iraq. Afghan insurgents, likely Taliban an al-Qaida fighters, are adopting methods proven effective in Iraq.2

For the entire year of 2005, the number of U.S. troop fatalities in Iraq per 1,000 U.S. soldiers was six, while in Afghanistan it was five; in other words, Afghanistan is just about as deadly a place as is Iraq.

Attacks by Taliban and allies have mushroomed since spring 2005.3 Scores of articles were published as of March 2005 with headlines like "Taliban Are Back" or "Revival of the Taliban."4 In May, Ken Sanders headlined a piece with "Iraq in Miniature."5 By September, Paul McGeough was writing from Spin Boldak in southern Afghanistan, "Welcome to Taliban Central, Pay at the Gate."6 In early 2006, the Taliban were producing DVDs showing their training camps in the Waziristan border region.7 Even more dramatically, the Taliban claimed to have established a Muslim State in North Waziristan, two weeks after Caroltta Gall reported in the New York Times that Pakistani efforts to root out insurgents in that area had faltered.8 Moreover, the Taliban circulate openly in Quetta, the capital city of Balochistan.9 The Taliban forces are now led by veteran, experienced, senior commanders such as Jalaluddin Haqqani, Mullah Dadullah and Saifullah Mansour and work closely with Al-Qaida. Increasingly Afghans, Chechans, Uzbeks and Arabs are fighting side-by-side, employing more sophisticated weapons and communications equipment, showing high levels of coordination, and clearly-defined battle tactics.10

The year 2005 was the most violent year of the insurgency since 2001.11 From January -- December 2005, 99 U.S. soldiers were killed in Afghanistan as compared to 55 killed between October 7, 2001 and the end of 2002. During 2002, 43 died, in 2003 the number was 46, and another 52 died during 2004. Even the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency admits that violence in Afghanistan increased by 20 percent during 2005, raising the level of insurgent threat to the highest point since late 2001.12 What is also surprising is that attackers now include Chechen, Uzbek and Arab fighters not merely along the Pakistan border, but in provinces well inside Afghan territory, in provinces such as Logar and Ghazni.13 The increased lethality and effectiveness of improvised explosive devices employed in Afghanistan is illustrated by two recent attacks -- on February 13, 2006 in Uruzgan Province and on March 12, 2006 in Kunar Province. Both attacks involved remote-controlled devices directed at armored U.S. Humvees on patrol and both killed four U.S. soldiers.

The insurgency's strategy is to bleed the enemy slowly, force a dispersion of its forces (increasing their vulnerability), and to bring a halt to any so-called reconstruction projects by raising the general level of insecurity.14 In May 2005, CARE International and an Afghan NGO issued a report, "NGO Insecurity in Afghanistan," wherein the fatality rate for NGO employees and the very high levels on insecurity prevailing in rural Afghanistan were documented.15 Aid workers hardly venture out beyond the confines of Jalalabad and Kandahar.16

The traditional guerrilla tactic of fading away into the villages and hamlets also raises the political cost for U.S. and Afghan forces as they bomb or attack villages, break into homes, killing and injuring civilians as occurred numerous times recently. At least 100 civilians have been killed by U.S. military action during the past year (see Table 1). The nighttime raids turn villagers against U.S. occupation forces.17 The corrupt and rapacious behavior of central government representatives does the same. For example,

The elders from the Sangin district of Helmand, which American planes bombed recently, said they had joined the small number of Taliban fighters because the government officials preyed on them and robbed them. 'The Taliban are in the villages, among the people,' said Ali Seraj, a descendent of Afghanistan's royal family and a native of Kandahar...With its corrupt and often brutal local officials, the government has pushed Afghans into the hands of the Taliban, said Abdul Qadar Noorzai, head of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission in Kandahar.18

|

|

| These photos by German war photographer, Perry Kretz, were taken in the fall of 2004 during a raid by U.S. occupation forces in Paktika Province. The first shows a raid in-progress by the Wolfhound unit of the 3rd Platoon, 25th Infantry Division. The second depicts the same unit photographing homeowner, Amir Mohammad, another example of the sexual humiliation perpetrated by the U.S. occupation forces upon Afghan villagers. More photos. |

A deputy director of Amnesty International heard on his recent visit to Afghanistan,

...numerous accounts of deeply offensive behavior toward women by U.S. forces, such as ransacking women's belongings and verbal abuse during weapons searches. 'We will kill to protect the honor of our women and children,' said one released detainee whose family had allegedly endured such treatment... We took scores of testimonies from individuals who alleged wanton destruction or theft during raids. We also heard tales of males being humiliated by, among other things, being forced to kneel on the ground with heads bowed while being blindfolded and handcuffed, sometimes hooded, in the presence of their families before being taken away for interrogation.19

| Table 1. Incidents where U.S. Military Action in the Afghan Theater Killed Civilians, March 2005 -- today | ||||||

| Wife and 2-6 children | F? | Adult/child | March 22, 05 | Waza Khwa village | Paktika | 3-7 |

| A boy | M | 10-14? | March 23, 2005 | Near Asadabad | Kunar | 1 |

| Gulbahar Aqa, father, 2 brothers, 4 women ,3 children | M,F | Adult, Adults, Adults, child | April 29, 05 | Zambori village in Charcheno district | Uruzgan | 10 |

| 8 civilians incl. women and children | F,M | Adult, child | May 8/9, 05 | Ali Shing district | Laghman | 8 |

| Shayesta Khan, 75 | M | adult | May 16, 05 | Sarbano village | Paktia | 1 |

| 5 civilian tribesmen | M | adults | May 21/22 05 | Lwara Mandai | North Waziristan, Pakistan border with Paktika | 5 |

| 17-25 civilians | M,F | Adults, child | June 30, 05 | Chechal village | Kunar | 17-25 |

| 5 civilians incl. a woman | M,F | adults | Aug 2, 05 | Ali Shing district | Laghman | 5 |

| Abdul Shahkor, 55, and wife, 16-yr-old boy, another man and woman | M,F | M-2, F-2, 1 child | Aug 8/9, 05 | Rauf village in Dai Chopan district | Zabul | 5 |

| 2 men, 1 woman | M,F | M-2, F-1 | Aug 9, 05 | Mara (Mareh) village in Deh Chopan | Zabul | 3 |

| Azizullah's wife | F | adult | August | Village in Dai Chopan area | Zabul | 1 |

| Noor Aziz, 8Abdul Wasit, 17 | M | child | Dec 1,05 | Asoray , North Waiziristan | Pakistan | 2 |

| Bal Khan and his mother, brother and two sons; Salam Khan and his mother and brother | F,M | M-4, F-2, child-2 | Jan 7, 06 | Dandi Saidgai village, 13kms north of Miran Shah, North Waziristan, 3kms from border | Pakistan | 8 |

| 4 women, 8 children, 6 men | F,M | F-4, M-6, Child-6 | Jan 12/13, 06 | Damadola village in Bajaur Agency, 40 kms from border with Kunar | Pakistan | 18 |

| Five civilians | ? | adults | Feb 2/3, 06 | Sarvan Kala village | Helmand | 5 |

| One civilian | M | adult | Feb 4, 06 | Shoraw village | Helmand | 1 |

| Two nomad women | F | adult | Feb 11, 06 | Bangi Dar village | North Waziristan, Pakistan | 2 |

| A woman | F | adult | March 8/9,06 | Kandi Bagh village | Nangarhar | 1 |

| Source: details for each incident provided in Marc W. Herold, the Afghan Victim Memorial Project. | ||||||

The expectation (and hope) is that U.S forces will periodically engage in outrageous behavior that can then be amply broadcast, serving to further alienate local populations. One recalls the incident in October 2005, of U.S. troops burning two Taliban bodies in the mountains north of Kandahar, a desecration of Muslim practice.20 Also, stories of torture by U.S. soldiers of abducted persons at U.S. forward operating bases fan the flames of the insurgency.

In effect, a stalemate -- or an empty space -- has been created where neither the U.S occupation forces nor the insurgency can prevail. Knowing this, each side adjusts accordingly in order to carry on the war-without-end at least cost.

On the U.S. side, efforts are being made to reduce the level of its ground forces in Afghanistan, which has both a financial savings effect, but far more importantly, it defuses political opposition in the United States. Lower levels of casualties and fewer troops abroad simply alleviate the pain experienced by injury, death and absence. It defuses the popular slogan, "Bring the Troops Home."

Another critical element of the United States involves having NATO forces do the ground fighting and actual occupation (including possibly carry out the very unpopular poppy eradication campaign). The idea here is that if a number of different countries contribute occupation forces and casualty levels remain what they have been over the past couple years, then the political price is bearable as it will be spread over different nations.

The training of local satrap army and police forces has lagged far behind schedule. A former Afghanistan policy officer at the State Department had this to say in late 2005 about Afghan forces,

The Pentagon has played a numbers game for three years with the fledgling Afghan army, which looks big on paper but has virtually no ability to move itself, sustain itself or fight by itself. In Paktika, Afghan soldiers were carted to operations in rented civilian trucks and quietly given MREs to keep them from going hungry.21

The U.S. military even admits that it carefully chooses where to send its Afghan satrap forces, never sending them into combat where they might suffer defeat.22

On the side of the insurgency, the least-cost adjustments are quite obvious. The use of remote-controlled or timed improvised explosive devices (IEDs) is a very low-cost, effective weapon -- no insurgent casualties and inexpensive to build. A slightly more costly weapon is the deploying of suicide bombers. Use of these two weapons has risen exponentially since 2004.23 During 2005, there were 17 suicide bombings (compared to five between 2002-4) and close to 20 during the first three months of 2006.24 To repeat, this has absolutely nothing to do with the weakness of the insurgency -- a message which is broadcast by the Pentagon, the lieutenant colonels at Bagram Air Base, and the Pentagon's corporate media boosters as part of the all-important information war. The effect of increased attacks has been to significantly elevate a general sense of insecurity across much of Afghanistan, even in such places as Kabul where foreigners are on curfew as of the early evening.

The thinking of the insurgency is that time is on their side. The slow bleeding of occupation forces, their deteriorating morale, continuing chaos in the countryside and towns of Afghanistan, and the high cost of keeping a sufficient military presence to maintain Afghanistan as "an empty space" -- at a military cost of about $1 billion a month25 -- will sooner or later lead to U.S. occupation fatigue. The Taliban and Al-Qaeda know about Afghanistan's war-filled history,

and the propensity of Afghan warriors for taking the long view of things and finding ways to ultimately defeat all the occupiers they have ever faced.26

Such will be compounded as the public realizes that average operational military costs -- amount needed to keep a soldier in each war theater -- in Afghanistan were and probably still are higher than in Iraq.27 The war in Afghanistan is costing close to $10 billion annually (Table 2) just in narrowly-defined military terms -- about 16% of total war expenditures. But the total expenditures in 2005 on the Iraq and Afghan wars were $100 billion, and are estimated to be at least $120 billion in 2006, that is, a 20 per cent increase despite plans to draw down troops in both areas.28 Douglas Holtz-Eakin, formerly at the independent Congressional Budget Office, said in January 2006 that "fighting terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan" is costing the United States $6-7 billion a month.

| Table 2. Current (2006) Military Costs of U.S. Wars | |||

| DoD annual spending | DoD monthly spending | DoD spending per minute | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iraq | $54 billion | $ 4.5 billion | $ 100,000 |

| Afghanistan | $ 9.6 billion | $800 million | $ 18,000 |

| Source: Mark Manzetti and Joel Havemann, "Iraq War Costing $100,000 Per Minute," Seattle Times, February 3, 2006. | |||

Thanks to National Priorities Project research, one can now estimate how much the Bush Administration's Iraq war (FY 2001 -- FY 2006) is costing each American state and community. For example, the cumulative cost per American household is $2,992 (based upon a total Iraq war cost of $315.8 billion). The cumulative cost to the state of New Hampshire, for example, is $1.3 billion.29 Simple arithmetic suggests then that cumulative cost for Afghanistan per American household is $680 and for the state of New Hampshire $342 million (based upon total military costs of $83 billion in Afghanistan).

Sooner or later, a war-weary American public will estimate that the soaring opportunity cost of this endless war in Afghanistan is simply not worth it. The $316 billion spent on Iraq could have been spent so that,

over 71 million people could have received comprehensive health care (36 million are currently uninsured); 61 million students could receive university scholarships; nearly 5 million workers could be employed as port container inspectors (only 6 percent of the 9 million containers arriving annually are currently inspected); or every child in the world could be given basic immunizations for the next 80 years...30

War critics' message that the war is not making the United States safer and is harming U.S. citizen taxpayers by saddling them with an enormous debt burden because the was is being financed by deficit spending, is gaining greater and greater acceptance even amongst conservatives.31

Michael Scheuer, a former counterterrorism official at the CIA in charge of tracking down Osama bin Laden, says

Osama doesn't have to win; he will just bleed us to death...He's well on his way to doing it."32

But such thoughts and other bad news need to be kept from the general public and that is where the Pentagon's news management enters the picture. It begins at the lowest level with the coterie of U.S. lieutenant colonels in Afghanistan who regularly: deny any civilian casualties occur as a consequence of U.S. military action; forbid media access to areas of U.S. bombing and raids; report on U.S. military successes in the field which allegedly regularly kill scores of enemy combatants; give preferential access to reporters who will portray the military very favorably (e.g., Lara Logan of CBS News is a favorite with a special penchant for hanging-out with U.S. Special Forces); repeatedly assert that the Taliban and its allies are on their last gasp and resorting to "desperate tactics'; and very likely under-report U.S. casualties. At a higher level, the U.S. military media center located in Fayetteville, N.C., which "would be the envy of any global communications company," functions to support U.S. government objectives around the world. Jeff Gerth wrote in the New York Times,

In Iraq and Afghanistan, the focus of most of the activities, the military operates radio stations and newspapers, but does not disclose their American ties. Those outlets produce news material that is at times attributed to the 'International Information Center,' an untraceable organization.... The United States Agency for International Development also masks its role at times. USAID finances about 30 radio stations in Afghanistan, but keeps that from listeners...33

Defenders of programs to influence media, such as Lt. Col. Charles A. Krohn, argue,

Psychological operations are an essential part of warfare, more so in the electronic age than ever...if you're going to invade a country and eject its government and occupy its territory, you ought to tell people who live there why you've done it. That requires a well thought out communications program.34

The Pentagon outsources programs for "media analysis.... and damage control planning" to companies such as the Rendon and Lincoln groups. In early 2004, the Rendon Group was hired to help Karzai improve his media image, though the effort was soon admitted to have been "...a rip-off of the US taxpayer."35

But the truth is too big to be hidden. Scott Baldauf, a long-time reporter of the Afghan scene, begins a recent article with,

Grim phrases are on the lips of diplomats, government officials, and aid workers in Kabul when describing Afghanistan these days. Narco state, political disillusionment, military stalemate, donor fatigue, American military pullout.36

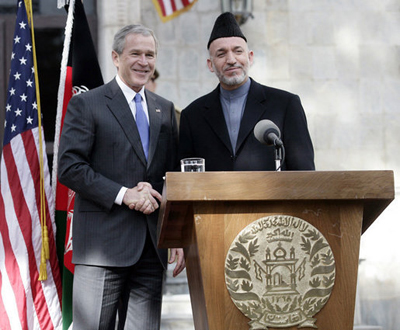

But such reality need not be dwelled on. The day after the director of the United States' Defense Intelligence Agency told the U.S. Congress that the Afghan insurgency was growing -- that "the volume and geographic scope of attacks had increased last year [2005]"37 -- President Bush alighted amidst great secrecy in Kabul to announce at a photo op in the heavily guarded Presidential Palace in Kabul,

"we are impressed by the progress that your country is making......we like stories of young girls going to school for the first time so they can realize their potential..."

Former Taliban defense minister, Mullah Obaidullah Akhund commented on the president's visit,

if the American president's visit had been announced in advance, the Taliban mujahideen would have greeted him with rockets and attacks. But Bush proved his cowardice by coming on a secret visit as a thief.38

Steven Simon, senior analyst at the RAND Corporation, is very blunt, "we are losing the war."39 In February 2006, ABC News reported that President Bush will ask Congress for an additional $65.3 billion for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, bringing total war spending close to the half trillion dollar mark.40

With what results? While some debate might exist as to whether the U.S. is "losing" the war in Afghanistan -- and the insurgency need not win to succeed -- what is beyond doubt is that the U.S. attempt to maintain Afghanistan as an "empty space" at least cost, has utterly failed.41 Afghan space is increasingly filled with insurgents, poppies, and violence as the cost of the U.S. occupation in dollar and body terms soars. If this is a success story, one wonders what failure might look like.

|

| The Ties That Bind. March 2006 in Kabul |

Conclusion: A very costly 'Empty Space'

The only real importance of Afghanistan to the United States since 9/11 is as part of grander designs. The attacks of 9/11 provided the Bush Administration with the opportunity to launch the attack upon Afghanistan under the pretense of bringing to justice the perpetrators of 9/11. When that goal failed and Osama Bin Laden took off into the mountains behind Tora Bora, the Bush Administration switched the rationale to bringing democracy to Afghans -- and education to girls -- made possible by the overthrow of the Taliban. More importantly, the bombing and invasion of Afghanistan provided the stepping-stone to the real target of Bush's America: Saddam Hussein and the oil of Iraq.

General Wesley Clark wrote in his book how after the president returned to the White House on Sept. 11, he and other top advisers began holding meetings about how to respond and retaliate. As Clarke writes, he expected the administration to focus its military response on Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda. He says he was surprised that the talk quickly turned to Iraq. "Rumsfeld was saying that we needed to bomb Iraq.... and we all said ... no, no. Al-Qaeda is in Afghanistan. We need to bomb Afghanistan." And Rumsfeld said there aren't any good targets in Afghanistan. And there are lots of good targets in Iraq. I said, "Well, there are lots of good targets in lots of places, but Iraq had nothing to do with it."42

Afghanistan fits into the grander design as pointed out by Ramtanu Maitra,

The landing of U.S. troops in Afghanistan in the winter of 2001 was a deliberate policy to set up forward bases at the crossroads of three major areas: the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia. Not only is the area energy-rich, but it is also the meeting point of three growing powers -- China, India and Russia.43

In effect, the sole value of Afghanistan is its space, pure and simple. Since only an empty space is involved, the implication is that such will be policed and maintained at least cost. Unlike in the colonies of the nineteenth century or the newly independent Third World nations after World War II, little will be done develop economic activity or infrastructure, a reality compounded insofar as Afghanistan offers neither resources nor a market. But the country does offer a space from which to project power and influence. In that sense, at a time when First World country finances are strained, the country represents the ideal neo-colony of the twenty-first century: an empty space to be operated at least cost.

However, the need to maintain a centralized, western-oriented puppet government in Kabul confronts traditional steadfast Afghan opposition to "Westernization," especially that variety which downplays religion, visibly displays corruption, ignores deep-seated ethnic rivalries, and seeks to undermine tribal and village politics and loyalties by imposing a central authority.44

From the attempt to maintain Afghanistan as an open space, a whole series of implications flow upon which I have elaborated in the previous three parts of this essay. Little effort will be devoted to reconstruction. The Bush Administration is cutting reconstruction aid to Afghanistan during 2006 from $1 billion to $600 million (compared to over $10 billion in military-related outlays). The majestic conclave held at Lancaster House in London in January 2006, which brought forth gushing speeches and bold rhetoric, will no doubt do little more than did similar conferences held in Tokyo in 2002 and Berlin in 2004.45 Certainly, some very useful projects are being undertaken which genuinely serve to improve the life of common Afghans, but these are taking place in spite of official neglect, questionable official priorities, and the occupation. For example, the partnership between Bangladesh's BRAC and the National Solidarity Program (NSP) of Afghanistan's Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation comes to mind.46

A second implication documented in part two herein is that the United States cares little about average Afghans' daily lives. So long as no insurgent activity or other perceived threat develops, whatever happens in an Afghanistan presided over by its grand satrap, Hamid Karzai, is just dandy so long as he serves as an echo box for the Bush administration.47 Look aside from poppies, violence, obscene affluence amidst a sea of poverty, deplorable indices of human development, corruption, narco and corrupto-mansions, a parliament with a vast majority comprised of anti-democratic elements (even if there are some 60 women MP's), etc. However, when signs of a reconstituted emergency begin to flicker, then only meager resources might be devoted to "win hearts and minds." When poppy planting begins to be perceived as possibly funding a revitalized insurgency, then the police and army forces will be dispatched to uproot the blooming stalks caring little for the fate of the dispossessed farmers.48 As the ever-astute Simon Jenkins noted, "the occupation of Afghanistan served only to turn the Taliban from opponents to supporters of the opium trade."49 As he demonstrates, Bush-Blair policy towards Afghan opium has been totally cynical: as reward to warlords for supporting Karzai, they turned a blind eye to the 2002-5 replanting. The campaign to eradicate poppies is directed primarily at the Pashtun South, not the northern regions under the control of Karzai's allies of the Northern Alliance.

A third implication is that the chimera of a central government needs to be maintained. In part three, I documented the ways in which 'Brand Karzai' is sold to the world public. No matter that the leader's power four years after the fall of the Taliban barely extends beyond the capital.50 Every effort will be expended by the U.S. to favorably spin Mr. Karzai and the progress in Afghanistan. When rare naysayers arise in the flaccid mainstream press, Mr. Rumsfeld declares war on the bad press.51 During the last two and a half years, the Bush Administration spent $1.6 billion to sway public opinion with the Pentagon alone accounting for $1.1 billion spent on media contracts.

Lastly, as the financial and economic costs of maintaining an empty space in Afghanistan have soared way above expectations, the United States is successfully prevailing upon NATO countries to do more of the heavy lifting. The Canadians, Dutch and British have been convinced to take over the policing and occupation in three of Afghanistan's most unsettled provinces: Kandahar, Uruzgan, and Helmand.

My analysis differs markedly and casts doubt upon much of what gets said in the mainstream. For example, on PBS' "NewsHour," on March 1, 2006, Afghan scholar Barnett Rubin bemoaned the pitiful levels of resources devoted to economic reconstruction especially when compared to the billions spent on the military. But that is exactly what is to be expected if Afghanistan is to be an empty space maintained at least cost. Another guest of the "NewsHour," Professor Nazif Shahrani, implored that Afghans should learn to better trust the Karzai regime and its U.S. backer. What I have documented herein is that average Afghans have every reason to distrust Karzai, the warlords and the opportunists around him who have done nothing for them.

The Afghan insurgent situation is more complicated than that of Iraq, which is largely a communal civil war.52 Afghanistan certainly has elements of that insofar as the vast bulk of insurgent attacks take place in the Pashtun provinces and, of course, the intra-mujahideen carnage of the 1990's represented such communal civil strife. But it now is overlaid with nationalist, religious ('living according to the laws of the holy Koran") and class dimensions. The insurgents are correct in seeing -- as I have documented herein -- the Karzai regime as an illegitimate one representing narrow, urban, secular class interests -- a kleptocratic, materialistic pseudo-bourgeoisie backed by a foreign government.

The whole grotesque spectacle is now teetering as a revitalized insurgency effectively employs its least-cost weapons. Once again, the common people of Afghanistan are and will bear the hardships -- as in the anti-Soviet war, the intra-mujahideen fighting, under the Taliban and U.S. bombs. In some places like Kandahar where banditry and daily violence -- the dead and injured come in many forms - are becoming unbearable, some residents look back longingly to the Taliban.53 In the empty space of Afghanistan, the simple folks -- people like Mohammad Kabir, Sahib Jamal, and Cho Cha -- are invisible in their everyday suffering.

Footnotes

1. Syed Saleem Shahzad, “US Digs in Deeper in Afghanistan,” Asia Times (February 9, 2005).

2. “Afghanistan More Dangerous than Iraq,” PakTribune (February 25, 2006).

3. See for example, Rachel Morarjee, “Afghanistan on the Brink of Chaos Again,” Dawn (July 1, 2005), Hamida Gafour, “Escalating Violence Has Roots Beyond Taliban,” Globe and Mail (January 19, 2006),and Mirwais Afghan, “No End in Sight to Afghan’s Years of Violence,” Reuters (January 26, 2006), and Tom Engelhardt, “Drugs, Bases and Jails. The Bush Administration’s Afghan Spring,” TomDispatch.com (April 5, 2005).

4. Jalal Ghazi, “Arab Media Reports: Taliban Are Back,” Alternet.org (Masrch 3, 2005), and Syed Saleem Shahzad, “Revivial of the Taliban,” Asia Times (April 9, 2005).

5. Ken Sanders, “Iraq in Miniature,” Online Journal (May 13, 2005).

6. Paul McGeough, “Welcome to Taliban Central, Pay at the Gate,” Sydney Morning Herald (September 12, 2005).

7. Mark Drummond and Bilal Sarwary, “DVD Role in the Afghan Insurgency,” BBC News (February 22, 2006).

8. Syed Saleem Shahzad, “Terrorism: Taliban Video Claims Muslim State in Waziristan,” AKI.news (February 6, 2006), and Carlotta Gall and Mohammad Khan, “Pakistan’s Push on Border Areas is Said to Falter,” New York Times (January 22, 2006).

9. See Abdullah Shahin, “Where the Taleban Train,” IWPR (March 7, 2006)./p>

10. These points are developed in the following articles (beyond the ones already mentioned in footnotes #3-5: Carlotta Gall, “Forgotten Afghan War: Taliban Remains Vibrant,” New York Times (June 4, 2005); “In Afghanistan, the Taliban Rises Again for Fighting Season,” The Independent (May 14, 2005); Jonathan Landay, “A New Taliban has Re-emerged in Afghanistan,” Knight Ridder (August 19, 2005); Syed Saleem Shahzad, “Osama Adds Weight to Afghan Resistance,” Asia Times (September 14, 2004); Sami Yousafzai and Ron Moreau, “Unholy Allies. The Taliban Haven’t Quit, and Some Are Getting Help and Inspiration from Iraq,” Newsweek (September 26, 2005); Scott Baldauf and Ashraf Khan, “New Guns, New Drive for Taliban,” Christian Science Monitor (September 26, 2005); Griff Witte, “Afghans Confront Surge in Violence. Foreign Suppot Seen Behind Attacks That Mimic Those in Iraq,” Washington Post (November 28, 2005); Kim Sengupta, “Remember Afghanistan? Insurgents Bring Terror to Country,” The Independent (January 17, 2006); Syed Saleem Shahzad, “Taliban Deal Lights a Slow-Burning Fuse,” Asia Times (February 11, 2006).

11. Carlotta Gall, “G.I. Death Toll in Afghanistan Worst Since ’01,” New York Times (August 22, 2005).

12. Katherine Shrade, “Intelligence Official Says Violence Increasing in Afghanistan,” Canoe News (February 26, 2006), and Walter Pincus, “Growing Threat Seen in Afghan Insurgency,” Washington Post (March 1, 2006).

13. Syed Saleem Shahzad, “US Back to the Drawing Board in Afghanistan,” Asia Times (October 5, 2005).

14. A recent article by Sean Naylor in Armed Forces Journal, a magazine for U.S. officers, presents a somewhat different interpretation, some of it of course quite self-serving. The author, Sean D. Naylor, while admitting that the Taliban have regrouped, argues that the Taliban have adopted a lie-low-and-wait strategy, so that the U.S. forces would come to believe that the enemy was defeated and start withdrawing its forces. When sufficient U.S. troops had left, the Taliban would launch a large-scale assault to take over state power. He explains the resurgence in fighting since mid-2005 by stating that newly arrived Special Forces units have taken the fight into the remote areas serving as Taliban sanctuaries. The problem with this analysis is that much of the fighting is still and increasingly outside such sanctuaries (for evidence, see sources cited in footnotes 5-9, especially Ken Sanders, “Iraq in Miniature,” Online Journal (May 13, 2005)). Moreover, the Taliban are not lying low and withholding high-profile, large-scale attacks upon U.S. because of a waiting strategy, but rather from the lesson learned that such attacks cannot be launched with the type of massive air power possessed by U.S. forces (Sean D. Naylor, “The Waiting Game. A Stronger Taliban Lies Low, Hoping the U.S. Will Leave Afghanistan,” Armed Forces Journal (February 28, 2006)).

15. Sanders, op. cit. The cited report.

16. Walsh and MacAskill (2006), op. cit.

17. See Declan Walsh, “Frustrated US Forces Fail to Win Hearts and Minds,” The Guardian (September 23, 2004).

18. Carlotta Gall, “Taliban Are Still Calling the Shots,” The Scotsman (March 5, 2006).

19. Curt Goering, “Losing Hearts and Minds in Afghanistan,” Minuteman Media (February 8, 2006).

20. Rupert Cornwell, “Film Shows US Soldiers Burning Taliban Corpses,” The Independent (October 21, 2005). See also “Grotesque ‘PsyOps’ in Afghanistan” (October 20, 2005); and here.

21.Chris Mason, “Déjà vu in Kabul,” Los Angeles Times (November 14, 2005).

22. See Colonel David Lamm’s (National War College) in Panel 1. Counterinsurgency and Military Strategy (Washington D.C.: conference “Winning Afghanistan,” American Enterprise Institute, Washington D.C. (October 2005)).

23. Excellent analysis in Griff Witte, “Afghans Confront Surge in Violence. Foreign Support Seen Behind Attacks That Mimic Those in Iraq,” Washington Post (November 28, 2006).

24. Irwin Arieff, “Attacks, Bombings Challenge Afghan Government: UN,” Reuters (March 8, 2006).

25. See Steven Kosiak, "The Cost of US Military Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan through Fiscal 2006 and Beyond" (Washington D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, January 4, 2006). See also bibliography.

26. Michael Scheuer, “History Overtakes Optimism in Afghanistan,” Terrorism Focus (The Jamestown Foundation) 3, 6 (February 20060 and especially fascinating analysis of Al-Qaeda’s strategy in his “Al-Qaeda’s Insurgency Doctrine: Aiming for a ‘Long War’,” Terrorism in Focus (The Jamestown Foundation) 3, 8 (February 28).

27. See Bradley Graham, "Disparity in Iraq, Afghanistan War Costs Scrutinized,” Washington Post (November 11, 2003).

28. Julian Borger, “Cost of Wars Soars to $440bn for US,” The Guardian (February 4, 2006).

29. “Local Costs of the Iraq War,” National Priorities Project (February 21, 2006).

30. From National Priorities Project as cited in Katrina vanden Heuvel, “The Costs of War,” The Nation (March 1, 2006).

31. James Sterngold, “Many Question Long-Term Cost,” San Francisco Chronicle (July 17, 2005).

32. Sterngold, op. cit.

33. Jeff Gerth, “Military’s Information War is Vast and Often Secretive,” New York Times (December 11, 2005).

34. Gerth, op. cit. The Lt. Colonel, now retired from being an Army spokesman is a professor of journalism at the University of Michigan.

35. Kim Barker and Stephen J. Hedges, “US Paid for Media Firm Afghans Didn’t Want,” Chicago Tribune (December 13, 2006).

36. Scott Baldauf, “Mounting Concern Over Afghanistan,” The Christian Science Monitor (February 14, 2006).

37. Pincus, op. cit.

38. Steve Holland and Sayed Salahuddin, “Bush Pays Surprise First Visit to Afghanistan,” Reuters (March 1, 2006)

39. Ambika Behal, “Still a War in Afghanistan,” United Press International (January 19, 2006).

40. “Bush Administration’s War Spending Nears Half-Trillion Mark,” ABC News (February 16, 2006).

41.Even the announced gradual transporting of U.S.-held prisoners in Guantanamo to the Bagram Base in Afghanistan supports the idea of Afghanistan as an empty space where those in power do not care. Reports have documented that conditions in the Bagram gulag are even worse than in Guantanamo. The Afghan regime is completely dependent upon U.S. support and hence will obey all restrictions upon access to or information about prisoners, a situation like the actual U.S. lease of Guantanamo. Transferred prisoners will simply descend into an invisible Afghan gulag, a legal void, an empty space where few know and those who care are denied access. As a former senior administration said, “for some reason people did not have a problem with Bagram. It was in Afghanistan” (Alec Russell, “US-Run Jail in Afghanistan ‘Worse than Guantanamo’,” Telegraph (February 27, 2006).

42. Reported in “Clark’s Take on Terror,” CBS News (March 21, 2004).

43. Ramtanu Maitra, “US Scatters Bases to Control Eurasia,” Asia Times (March 30, 2005).

44. A similar point is made in Scheuer (Feb. 14, 2006), op. cit.

45. See Mike Whitney, “Buildings Down, Heroin Up,” Counterpunch (February 2, 2006).

46. See “News Updates of BRAC Afghanistan (Bangaldesh)” (2005).

47. See my essay, “Karzai as a Bush Echo Box,” cursor.org (September 6, 2002).

48. “Grow Opium or Die: Afghan Farmers Say Choice is Stark,” Agence France Presse (March 10, 2006).

49. Simon Jenkins, “Blair’s Latest Expedition is a Lawrence of Arabia Fantasy,” The Guardian (February 1, 2006). See also Tom Engelhardt, “Afghanistan: Drugs, Bases, and Jails,” Mother Jones (May 2, 2005).

50. Declan Walsh and Ewen MacAskill, “Four Years After the Fall of Taliban, Leader’s Power Barely Extends Beyond the Capital,” The Guardian (March 1, 2006).

51. Emad Mekay, “Rumsfeld Declares War on Bad Press,” Inter Press Service (February 22, 2006).

52. Stephen Biddle, “Seeing Baghdad, Thinking Saigon,” Foreign Affairs (March-April 2006).

53. “Afghan City Mourns Its Lost Children, Looks Back to Taliban,” Agence France Presse (April 11, 2005), Michael den Tandt, “New-look Afghanistam Leaves Mullah Longing for Days of Taliban,” Globe and Mail (February 10, 2006), and especially, Chris Sands, “Kandahar Residents Live ‘Under a Knife’,” Toronto Star (January 16, 2006).